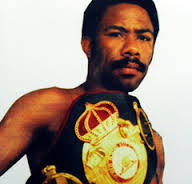

Eusebio Pedroza: Looking Back at a World Champion When A World Title Still Meant Something in Boxing

[AdSense-A]

Panama, birthplace of Roberto “Manos de Piedra” Duran, the former lightweight king and conqueror of a prime Sugar Ray Leonard. Mr. Duran, though legendary and most recognizable, is but one of many fighting sons borne from the womb of the Central American nation. Many panameno were weaned in the blood, sweat, and tears of the fight game. Before and after their collective hero donned a pair of gloves Panamanian pugilists have fought to carve out an enriched experience and bathe themselves in boxing glory. One of those men was a lanky Afro-Panamanian by the name of Eusebio Pedroza.

Among the rickety shacks of Panama City’s Maracon district, shacks originally designed for workers of the Panama Canal, Eusebio grew up. He was spindly throughout his physical development and that size eventually proved useful, as many of his opponents in the paid ranks would find out.

When he finally did turn pro in April of 1973, he reeled off nine straight victories against less-than-spectacular competition. In his tenth professional bout, he bit off more than he could chew in a more experienced Colombian featherweight named Alfonso Perez, who was 16-0-2, 11 KO’s at the time. Perez bowled over the lanky Panamanian in three.

“El Alacran” kept moving, however, gradually facing better competition and learning on the job. Pedroza managed a five-fight win-streak after his initial defeat before he got the call for a title shot against bantamweight Alfonso Zamora, a significantly shorter but very powerful Mexican fighter who had not let a single opponent see the final bell. Unfortunately for the green challenger, he wasn’t the one to break up the knockout streak, as he was flattened in the second round by a pinpoint right hand that was thrown behind a stiff jab to the body and then followed up with picturesque left hook. Amazingly, Eusebio beat the count of ten after the vicious combo but his legs, giving the appearance of a newborn horse trying to get its gallop right, was in no shape to continue and the referee stopped the bout.

A mere three months later, Eusebio did slightly better, lasting six rounds with undefeated Venezuelan, Oscar Arnal. Not much is known of Arnal, but like Zamora, he seemed to have had some solid pop in his punches. Oscar Arnal finished his career with a mark of 24 kayos in 30 wins.

Most men can’t cope with loss, especially when it happens in such devastating fashion, but despite the roadblocks, the Panama City native wasn’t discouraged. In fact, he was spurred on by defeat and sped forward towards title town, overcoming three Latin pugilists before WBA featherweight champion and Spanish southpaw, Cecilio Lastra, issued him a contract. Both men signed and the match was set for April 15th, 1978 in Gimnasio Nuevo Panama, Panama City, Panama.

The bell sounded for Pedroza’s second attempt at gold and from the get-go Eusebio was the boss, jabbing regularly and circling to his opponent’s right in an effort to stay away from the left hand power of the champion. The strategy was an excellent one and pressed Lastra into engaging, allowing for counter-punching opportunities. One of these opportunities presented itself in round four when the champion tried to land a straight left. The ill-intended punch was avoided and met with an accurate and strong left hook on the point of the chin, putting Lastra down. The Spaniard was not in serious trouble, however, and continued to fight in a similar manner which preceded the knockdown.

In round five, the Panamanian began to put his length to use over the 5’5” titleholder, as he mixed in many lead right hands which were not only too long to be countered, but also too quick. Pedroza repeated his success over and over, round after round.

In the latter stages of the fight the challenger changed pace, boxing as well as pressing. This gave him a clearer advantage than he had had before and in the thirteenth segment, after an exchange by both men, Pedroza landed a stinging right and left uppercut which put the champion to a knee. Looking distraught and winded, Lastra stayed down until he was nearly counted out. The in-ring moderator hesitated briefly after assessing the Spaniard’s condition, but allowed the match to continue. “El Alacran” rushed over, seized the moment and never relented, punishing the WBA’s belt-wearer. Cecilio made frequent attempts at tying his taller foe up to stem the fistic tide, but his grapple tries bore little fruit. Eusebio kept throwing strikes and eventually found a clean one at range, a powerful right hand.

The punch rocked Lastra and forced him to the canvass once again. The champion, proving his mettle, found the will power to get up just as he had done before, but the ref had seen enough and halted the contest. Pedroza, overjoyed by his newfound recognition as champion, jumped up and down until his corner men hauled him off and paraded him around the ring.

With that triumph, “The Scorpion” joined Roberto Duran and Jorge Lujan as then-current Panamanian titleholders. The three continued winning together until 1980, when Duran lost the rematch to Sugar Ray Leonard and Lujan dropped a split decision to undefeated Puerto Rican, Julian Solis. Pedroza was the only one to not have his streak interrupted, as he overcame Mexican journeyman, Ernesto Herrera; Puerto Rican veteran, Enrique Solis; former Arguello and Gomez victim, Royal Kobayashi; Panamanian youngster, Hector Carrasquilla; faded Mexican legend, Ruben Olivares; Papua New Guinea native, Johnny Aba; 5’0” Japanese battler, Spider Nemoto; Argentine aggressor, Juan Domingo Malvarez; the inexperienced, Sa-Wang Kim; and undefeated American prospect, Rocky Lockridge.

The Lockridge fight was the biggest test he had at that stage of his tenure as WBA champion, and the most controversial of his title defenses up until that point. Rocky Lockridge seemed to win most of the first ten rounds, but Pedroza rallied late and came away with split decision verdict. It wasn’t just the scoring which rubbed some people the wrong way though. Rocky’s promoter Bob Arum and manager Lou Duva accused the champion of taking a foreign substance during the fight. The video footage confirmed that something was indeed placed in Pedroza’s mouth by his manager Santiago Del Rio, but Pedroza rebutted the accusations telling an interviewer: “I take some ice in my mouth between rounds. I don’t need anything during a fight. I am in too good condition to have to take anything like that.” Eusebio took a urine test afterwards to help dissolve any suspicion.

Despite what had happened in New Jersey against the American upstart in Lockridge, the belt holder racked up ten title defenses in a little over two years; a stellar number by almost anyone’s measure, especially in comparison to that of most modern champions. Pedroza kept his foot on the gas afterwards, facing some of his best competition to date. In succession he faced Pat Ford, Carlos Pinango, Bashew Sibaca, Juan Laporte, Rudy Alpizar, Bernard Taylor, and Rocky Lockridge in a rematch. He scored victories over all but Alpizar (no contest) and Taylor.

Eusebio’s fistic exhibition against the aforementioned Pat Ford may have been his showcase bout. Ford displayed substantial pugilistic wherewithal when he managed a majority decision loss against Salvador Sanchez, the highly touted featherweight whose life was struck short by a car accident. “The Scorpion” handled Ford significantly easier than Sanchez did, highlighting his entire repertoire of boxing goodies: jabbing, moving, slipping, landing clean power punches, and showing us all his renown ring generalship. The scorecards reflected Pedroza’s dominance. He won by the margins of 120-109, 120-113, and 118-113.

His title defenses against steel-chinned Juan Laporte and top-notch boxer Bernard Taylor were violent struggles. Pedroza managed a close points verdict versus the Puerto Rican, but he had to settle for a stalemate against the sprightly young American.

The historical reign continued as the dark-skinned featherweight pressed on, albeit against lesser opposition than before (maybe as the result of a couple scares). Pedroza went on to decision Rocky Lockridge in a rematch; won by a wide margin on the cards in his bout with Jose Caba; had little problem outboxing the undefeated Venezuelan, Angel Mayor; TKO’d the tough American ring veteran in Gerald Hayes; and outclassed former bantamweight champion and fellow countryman Jorge Lujan before traveling to the United Kingdom and entering the squared circle to pit wits with Irish phenom, Barry “The Clones Cyclone” McGuigan.

By this time, Pedroza was “the man” at 126 and had been since Salvador Sanchez’s tragic passing. McGuigan came in as the number four rated contender, largely based on his bettering of Juan Laporte over ten rounds; but what the Irishman was really made of was a serious question that was yet to be answered. In front of a raucous crowd of twenty-six-thousand, both men sought to verify their standing.

Bell ringing and a torrential downpour of cheers filled the air to start the fifteen-round featherweight championship contest. From second number one “The Clones Cyclone” assumed the role of aggressor and “El Alacran” took ample opportunity to exploit the size of the ring, which was the largest available. Eusebio jabbed and moved; Barry tried offsetting the champion’s long left hand with a jab of his own. The first segment ended with both fighters active, but with little in the way of picking a clear winner. The second was a different story. McGuigan, as focused as a sniper waiting for his target, found Pedroza repeatedly with power shots, one of which was a left hook that the Panamanian seemed be bothered by.

Pedroza went about reversing his fortune in the next go-round, popping his jab on the challenger’s face and connecting with bolo punches. It looked as if titleholder’s experience was starting to show but the challenger fought back hard. They fought tit for tat through most of seven rounds until McGuigan unleashed a wicked right hand-left hook combination that Pedroza never saw coming. The defending belt holder was sent sideways to the floor and was visibly hurt. Pedroza regained his composure as fast as he could and he beat the count of eight. The 5’6” brawler pounced like a tiger when the referee waved the boxers forth, landing a number of quality strikes to the champion’s head. It wasn’t enough though. Like the gritty and determined battler he was, Pedroza not only made it to the foreclosure of the round, he fought back and bounced a few power shots off of Barry’s face.

Panama’s own persisted in landing in the following segments. The problem was, none of it deterred the rugged challenger. McGuigan kept marching forward with unfettered concentration and proceeded to land the more telling wallops until the final bell had sounded. When the scorecards were read, a new featherweight champion had been crowned, but “The Scorpion’s” $1 million dollar payday helped quell the loss of his alphabet strap and the ending of his much talked about run.

With money in the bank and a warm welcome home, Eusebio settled in and took it easy before thinking about pairing up with another professional. When he did decide that boxing was worth another try, after an entire year of absence, he moved up to lightweight and suffered a split decision loss to 21-1, 13 KO’s, Edgar Castro. This prompted a five year layoff and a similar return to 135, where he gave it one last go before being retired for the final time by Mauro Gutierrez, a Mexican journeyman.

After the allure of the unbridled ferocity of boxing left his veins, Pedroza was enshrined in Canastota, New York, the home of the International Boxing Hall of Fame in 1999. The former champion’s post-boxing career also saw him hold various positions within the Panamanian government, one of which was the chief of general services. This position entailed providing utilities to the poor of his nation, a situation he was all too familiar with growing up.

In summary: slander has been leveled against Eusebio for being a dirty fighter. Truth be told, he could be (see his bout with Laporte). But that doesn’t encapsulate the totality of his remarkable ability. Pedroza was much more than that. Being dirty doesn’t get you nineteen consecutive title defenses, nor does it allow one to stand atop a good division for years. It can’t account for his record of 41-6-1,25 KO’s, or his innate defensive radar which allowed him to slip so many punches. What about his quick hands and feet? How about his accuracy?

His craft is served justice by focusing on all of his fistic tools. The man could win with all and he could win with some, but most importantly, he won.