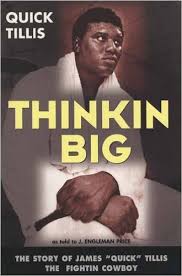

Thinkin Big: The Story of James “Quick” Tillis – RSR Book Review

By Chris “Man of Few Words” Benedict

By Chris “Man of Few Words” Benedict

“That’s the story of my life, people helpin me, me helpin them.” The man who still calls himself “The Fightin Cowboy” poignantly summarizes his personal philosophy this way in his memoir Thinkin Big. He adds for emphasis, “That’s the way it oughta be.”

In a sport where savagery is celebrated and empathy seen as a mortal weakness, James Tillis stands out as one of boxing’s curious anomalies. The renowned sports writer Jimmy Cannon once belittled Floyd Patterson with the caustic remark that “compassion is a defect in a fighter”. Had he lived long enough to cover the career of “The Fighting Cowboy”, it is likely that Cannon would have thought along the same lines of Tillis, who himself admits that he could never get angry enough at an opponent to want to hurt him. James it seems had a heart as big as each fist, damn near the size of a canned ham. Still does.

In its original incarnation, the book was composed on now-yellowed scraps of paper in a Tulsa jail where Tillis made productive use of a 30-day sentence for failure to pay child support. He is the first to admit that women were the one vice that weakened the resolve of a man who abstained from drink, drugs, and tobacco. The rough manuscript was eventually turned over to co-writer J. Engleman Price who, a few factual inaccuracies and a bit of a disjointed narrative aside, did a credible job of shaping it into Thinkin Big-The Story of James Quick Tillis, The Fightin Cowboy.

“Being a cowboy has always been my first love, with boxing comin a close second,” writes Tillis, longing for simpler times as though he had been born into the wrong era. “Quick” credits his lifelong infatuation with cowboy culture to his part-Choctaw Indian great-grandfather the Tillis kids called Uncle Pete, a “hand” who would break wild horses and brand cattle. Little James would snuggle into Uncle Pete’s lap and listen, silently spellbound, to stories like the one where Frank and Jesse James hid out in his camp one night while on the run from a posse following a bank heist.

As for Tillis’ athletic prowess, that was passed down to him from Uncle Pete’s son, James’ grandfather Theodore Roosevelt Hawkins (or Jack), a 300-pound marvel of masculinity who would harvest cotton six days a week, attend services on the Sabbath, then head down to the field to play ten innings of baseball, not content with nine evidently. Offered a contract with the barnstorming Kansas City Monarchs of the Negro American League in the 1930s, Jack turned it down to stay near his family. Driven by an unruly libido, Grandpa Jack is said to have gotten a little too cozy with the livestock when no willing woman was to be found. A similar and (it should be made clear) untrue rumor concerning “Quick” circulated around his class and led to his first fight, a schoolyard rumble that landed him a 10-day suspension.

A multi-sport star who excelled at basketball and track and lettered in football as a sophomore tight end for McLain High School at 173 pounds, James thrived athletically despite enduring a steady and financially obligatory diet of Spam and government cheese. His father, who had dragged a young James to juke joints and gambling shacks in a misguided attempt to make a man out of his five year-old son, later “dropped us like a bad habit”, leaving an ill-equipped “Quick” to prematurely assume the role as the male head of the Tillis house-with Mama to keep him in check, of course. The Tillis patriarch would continue to make his presence known in a variety of unsavory ways, however, such as the time he stumbled drunkenly onto the field during one of James’ junior high football games playing for the Carver Cats and pissed on the 50 yard line.

It would ultimately be boxing that would allow “Quick” to channel his adolescent frustration and natural aggression in a positive direction. Watching Cassius Clay, “a heavyweight dancin on air”, take on Sonny Liston, looking “like he owned the world”, on the little black and white TV set situated on the family’s linoleum floor on February 25, 1964 changed it all for James who was convinced that he heard the word of God coming through Clay’s brash post-fight declarations of greatness, boasts that got the seven year-old Tillis thinkin big for the first time in his life.

Coached by Ed Duncan, who Tillis calls “the father I never had”, he fought in a smoker at the Armory Gym in Henryetta, OK at 16, taking out Leon Bruner with a blindingly fast ambidextrous attack that earned him the nickname “Quick” from his cousin and teammate Keith. A victory in the 1975 Regional Golden Gloves earned James his first trip away from home to the Nationals in Knoxville, TN where he got to rub shoulders with the likes of Michael and Leon Spinks, Thomas Hearns, Greg Page, and John Tate. The following year brought another win at the Regional Gloves, but a first round loss to Page at the Nationals in Miami’s Orange Bowl.

Being transplanted to Chicago for the germination of his professional career would prove a rude awakening for Tillis, as he not only had his duffel bag snatched from his feet where he set it down to snap a picture of the Sears Tower upon his arrival, but stayed in an apartment with “walls made out of paper and glued together with roach shit”, sleeping in the same bed that the previous occupant had died in. He would earn all of $100 for his pro debut, a first round knockout of Ron Stephany.

“Quick” recalls the majority of his early followers being “drunks, pimps, and whores” and supplementing his meager prizefighting income as a runner on the floor of the Mercantile Exchange where he was brought up from the pits to meet Jim Kaulentis, a “risk taker” who would roll the dice on the advancement of Tillis’ career along with four other investors. Things began to take off from there. James trained with Spider Webb and Archie Moore, Jimmy Ellis and Luis Rodriguez, and reeled off 20 consecutive victories, 16 of them knockouts.

Reportedly turning down a $1 million step aside offer from Dennis Rappaport that would have allowed his fighter Gerry Cooney to face Mike “Hercules” Weaver for the WBA heavyweight title, James claimed the opportunity for himself. Sitting ringside, Larry Holmes would tell HBO broadcaster Larry Merchant that after he knocked out Renaldo Snipes and Cooney, he wanted the winner of this fight. In a titanic struggle of what he referred to as King vs. Godzilla proportions, James would remember little else beyond sucking air and tiring in the later rounds, prompting Angelo Dundee to slap him across the face after the eleventh, the same way Gil Clancy had done to awaken Emile Griffith from a sleepwalking stupor in the first Benny Paret fight, and scream “You don’t want to win? You want to be a fuckin bum your whole life?!” Dundee’s tough love would go for naught and James would “end up with $60,000 and a broken heart”. Weaver paid a conciliatory post-fight visit to Tillis’ dressing room, touching off a brotherhood that endures to this day.

Tillis would add his voice to the testimonials proclaiming Earnie Shavers as the hardest puncher in the 1970s/80s heavyweight division. “Quick” would survive not only an after the bell left/right sucker-punch at the end of the second round of their 1982 bout, but a knock down in the ninth which had Tillis hearing a cacophony “like a bagpiper who fell over dead with no one to stop the last note” and suffering a hallucination wherein he saw “little blue rats scamper out to smoke cigarettes and eat Spam sandwiches”. Tillis eerily popped up like a horror movie monster the half-naked co-eds thought for sure was dead, and recovered sufficiently to earn the unanimous decision, but later received a lecture from Bill Cosby about his performance thrown into for good measure.

He would fall victim of an 8th round TKO to his amateur adversary Greg Page (who then held the USBA heavyweight title) at the Houston Astrodome as the co-main event to Larry Holmes’ defense against Randall “Tex” Cobb, a lopsided annihilation which would cause Howard Cosell to end the broadcast abruptly, dismissing out of hand the notion of conducting post-fight interviews. “Not for this”, he concluded in disgust. Afterwards, he would refer to the travesty as an “advertisement for the abolition of this quote-sport-unquote”. He would make good on his vow to never sit behind the broadcast table for a fight again, a decision for which a self-congratulatory “Tex” Cobb would acerbically take credit as a “gift to the sport of boxing”.

Hollywood provided a high profile diversion, as Tillis played Oprah Winfrey’s lover Buster Broadnax in Steven Spielberg’s 1985 film The Color Purple, telling Danny Glover as she is escorted to the juke joint’s dance floor by another man, “First time I ever been knocked down without throwin a punch.” James would get up from a very real fourth round flash knockdown to drop a narrow points loss to 19-0 knockout artist Mike Tyson. “Quick” was the first fighter to take boxing’s angry young man the full distance and many argue ( James among them) that “Iron Mike” benefitted from a hometown decision in Glens Falls, NY. Tillis’ improved endurance was due to a recent diagnosis of food allergies and vitamin deficiencies resulting from his preference for soda pop, dairy, and complex carbohydrates, adjustments to which corrected a slow pulse, weak adrenaline, and prostate irritation.

James Tillis also served as then-cruiserweight champion Evander Holyfield’s introduction to the heavyweight division in 1988, forced to retire in his corner after absorbing a hellacious bombardment in the 5th round. This bout was marred by the intervention of the always excitable Lou Duva and Tillis’ manager Beau Williford (whose name is changed in Quick’s book to Willy B in a not-so-subtle effort to protect the not-so-innocent) when Evander and James both continued swinging away following the end of the second round. Duva held Tillis’ arms behind his back and Holyfield, had he struck “Quick” in this compromising position, would certainly have been disqualified by referee Richard Steele.

But, James “Quick” Tillis is far more than a Where Are They Now? curiosity, an answer to a trivia question, or a page ripped from the Who’s Who Book of 1980s Heavyweight Contenders.

Do yourself a huge favor and pick up a copy of his autobiography and see for yourself. Trust me, I haven’t even scratched the surface here. While it might seem trite or hackneyed to assert that a memoir is written in a conversational style, while reading Thinkin Big you truly do feel, given James Tillis’ endearingly oddball vernacular, as though you are sitting around a campfire beneath a canopy of constellations, the logs crackling and coyotes howling from a nearby mountaintop, listening to “Quick” spin some yarns about his good old days-and the new ones too-as “The Fighting Cowboy” while roasting marshmallows and brewing a fresh pot of cowboy coffee.

And that, my friend, makes for one of those nights that you just don’t want to end.