G.I. Joe Louis: The Brown Bomber Goes to War

By Chris “Man of Few Words” Benedict

During a highly publicized White House tête-à-tête bringing together the Commander-in-Chief and World Heavyweight Champion, Franklin Roosevelt made a spectacle of feeling Joe Louis’ biceps while declaring, “These are the arms we need to beat the Germans.”

The seventh of eight children born in a cramped Alabama shack to his black father Munroe and half/Cherokee mother Lillie-sharecroppers whose parents had been slaves-Louis may have initially been politically indifferent but his co-manager John Roxborough’s brother Charles (Michigan’s first black senator) had opened his eyes. So Joe must have been aware that FDR’s hand, the very one now shaking his own in anticipated congratulation, was in no hurry to put pen to paper issuing to the War Department an executive order which would have desegregated the U.S. military into which Louis would later be conscripted and play a large part in changing. More appalling still, Roosevelt-fearful of antagonizing or isolating Southern constituents whose votes would need to be counted upon for other public policies and programs, refused to enter anti-lynching bills into consideration for Congressional action. Even Eleanor would be more forgiving of Franklin’s sexual infidelity than of this iniquitous pretense.

Max Schmeling, for his part, had no use for the policies of the Nazi hierarchy except when it benefitted him in relenting to the role of pawn in Hitler’s expansionist chess match which saw pieces already moving across the board with the annexations of Austria and Czechoslovakia. Sure, he had dinner with Hitler at his personal request but was later to protest, as retold by boxing’s wise old man on the mountain Bert Sugar, “I turned the Fuhrer down four times. One did not turn him down five times.” Not quite five months after the second Louis fight, Max would be summoned to the office of Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels to answer for having given shelter to two young Jewish boys during the deadly pogrom known as Kristallnacht (or, night of broken glass). Schmeling would also later assist many Jews in escaping Germany and, thus, detention, selection, experimentation, or outright extermination.

Fundamentally discredited by winning the vacant heavyweight title on a technicality in 1930, Max had been hit below the belt by Jack Sharkey and ordered by his manager Joe Jacobs (who, incidentally, was Jewish) to remain on the canvas, crying foul and demanding a disqualification. Schmeling was snidely derided as the “low-blow champion” and reentered Germany a disgrace to the supposed master race. Ironically, his next homecoming was the polar opposite, welcomed back and bestowed with more honor in defeat than victory after dropping the championship to Sharkey by way of a deeply disputed split decision in their rematch.

If the controversial loss to Sharkey made a martyr of Schmeling, his 1936 12th round knockout of Joe Louis transformed him into an Aryan, Nietzschean superman. Goebbels, who had initially suppressed any and all press coverage of Max’s Darwinian battle with a black man, ultimately and advantageously saw fit to oversee the distribution of a photograph of him listening to the bout on the radio seated beside Schmeling’s blonde-haired, blue-eyed wife Anny. Hitler ordered the fight film to be played indefinitely from that point forward in all movie theatres as a prelude to the evening’s main feature. It was titled Schmeling’s Victory-A German Victory. While Joe Louis was being torn apart in American periodicals as a fabricated myth and crumbling god, Schmeling was content to play the part of propaganda tool for the Third Reich. Knowing how well thought-of Schmeling was stateside at that point in time, Hitler called in a favor and asked the boxer to essentially serve two masters, acting as a secret emissary to the New York offices of the U.S. Olympic Committee to beg them to reconsider their boycott of the upcoming Berlin games. The ploy worked and, as far as the enraged Nazis were concerned, a little too well. Jesse Owens, a good friend of Joe Louis, won four sprinting and long-jumping gold medals and pissed on Hitler’s parade.

To make matters worse, Schmeling was later passed over by the New York Boxing Commission in favor of Louis as the mandatory challenger to new heavyweight champion James J. Braddock for fear that a victorious Schmeling would hold the title hostage back in Germany at Hitler’s bidding. There was more at play than jingoistic pride. The guarantee of a $300,000 purse in addition to an indefinite 10% share of Mike Jacobs’ promotional earnings exclusive to his contractual arrangement with Louis very much eased the turning of Braddock’s head in a direction other than Schmeling’s. Behind the scenes politicking notwithstanding, The Brown Bomber made a nightmare of the Cinderella Man’s fairy tale and, after twenty-two long years, a black man was once again heavyweight champion of the world.

The stage was now set for the Louis and Schmeling rematch. The stakes could not possibly be higher and its sphere of influence virtually all-encompassing. Never before or since had the mania surrounding a prizefight enveloped not only boxing aficionados and casual fight fans but the entire international community which heavily suggested that, for all intents and purposes, the opening battle of World War Two would take place in the Bronx at Yankee Stadium on June 22, 1938 before more than 70,000 eyewitnesses. No puffery or superfluous publicity necessary. The pre-fight hype wrote itself. Even the ever-stoic Louis was, on this occasion, not above prognostication. Asked by a reporter while sitting atop his rubbing table as Jack Blackburn taped his hands how many rounds he thought the fight would last, Louis simply smiled and held up one finger.

The world came to a stop on fight night. Time stood still. Business as usual? No such thing. Radios could be heard transmitting the proceedings from cars, bars, restaurants, apartment buildings, movie houses, any and all public gathering places. The same held true in Deutschland despite the fact that the ring introductions would not be made until just after 2:30 am Berlin time. As it happened, German audiences would not be made to wait terribly long to head to bed and catch up on their beauty sleep. While they may have been left in suspense as to specific details of the bout’s outcome, it could not have been difficult to surmise that the end was soon in coming. Cornering Schmeling, Louis let loose with a barrage of combinations which kept Max backpedaling, never the aggressor. One particularly devastating left to the solar plexus caused Schmeling to shriek in agony loud enough to be heard several sections back. A punishing right cross sent Max tumbling onto his backside in a weird sit-and-spin semi-circle before regaining his footing. This was merely a minute and a half into the fight but Joseph Goebbels had heard enough and pulled the plug on the German broadcast.

For what it’s worth, the Teutonic listeners didn’t miss much. The moment Schmeling found himself standing upright, he was smothered by Louis and floored twice more in quick succession. At 2:04 it was all over, trailing only John L. Sullivan’s 20-second dismantling of Sylvester Le Gouriff in 1884 as the fastest knockout in heavyweight championship history. At least the German citizens were spared from having to decide which was worse. Whether Schmeling’s trainer Max Machon took it upon himself to toss a white towel of surrender into the ring over the challenger’s prone form after referee Arthur Donovan had already halted the action. Or whether Donovan dismissively and disdainfully tossed the towel aside “where it hung on the ropes as limp as the German himself” according to one sportswriter.

Having used his mighty arms to vanquish the dreaded German, to the delight of Franklin Roosevelt and millions more besides, Louis would continue to adopt a hands-on approach in FDR’s fight against fascism, despite originally supporting Republican candidate Wendell Willkie for president in 1940 due to his strong stance on civil rights, while a dishonored Schmeling was put to use as a paratrooper upon returning home. Joe donated the entirety of his purses from title defenses in early 1942 against bum-of-the-month club members Buddy Baer and Abe Simon (both of whom he was meeting for the second time) to the armed forces, netting in the neighborhood of $154,000 for the Army and Navy respectively after taking into consideration additional contributions made by Simon, Baer, and promoter Mike Jacobs. The IRS nonetheless declared both of these charitable endeavors as taxable income, compounding the financial burdens that would plague Louis to the end of his days.

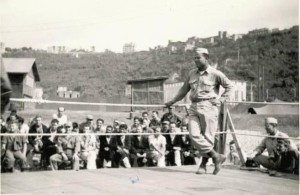

Two weeks before the fight against Simon, Louis found himself in the familiar confines of Madison Square Garden. Not inside a boxing ring but onstage between sets by the Lucky Millinder Orchestra at a fundraiser for the Naval Relief Society. Never comfortable as a public speaker, Louis was in need of a little pearl of wisdom and turned to Lucky who suggested the champ tell the gathering that “We’ll win because God is on our side.” Upon reaching the podium, Joe said instead, “I’m only doing what any red-blooded American would do. We gonna do our part and we will win because we are on God’s side.” Although he had flubbed Lucky’s line, Louis received a rave review from none other than Franklin Roosevelt who advised the Army to use the misspoken words as the tag line on a recruitment poster below a photo of Joe dressed in fatigues and tactical helmet and brandishing a bayonet. By design, the only hand-to-hand combat Louis would engage in would occur in makeshift boxing rings where he would display his pugilistic skills for the diversionary pleasure of the servicemen (both black and white, at Joe’s insistence) experiencing some rest and relaxation when not keeping the world safe for democracy.

“Tired of boxing, sick and tired of the training and the traveling,” Louis had volunteered for the Army three days after the Buddy Baer fight and ridden with his other manager Julian Black in a chauffeur-driven limousine to Camp Upton on Long Island where Brookhaven National Laboratory now stands. “They gave me my uniform and sent me over to the colored section,” reflected the heavyweight champion become private first class. Joe was granted a two-week furlough to attend the funeral of his beloved trainer Jack Blackburn who had died following a bout with pneumonia and fatal heart attack which unsprung the mortal coil of the man who had once struck fear into the hearts of Joe Gans and Sam Langford. Louis and his wife Marva were among the 10,000 mourners who paid their respects to “Chappie” at Chicago’s Pilgrim Baptist Church. “When the dirt went down on that coffin,” wrote Joe solemnly in his memoirs, “I knew my life would never be the same again.”

After returning to camp Louis would fight his first exhibition, against George Nicholson at Fort Hamilton in Brooklyn, and complete basic training. Joe was then transferred to a cavalry unit in Fort Riley, Kansas where he would be promoted to corporal and finally sergeant. It was there that Louis would assist a young private named Jackie Robinson with the integration of the camp’s football and baseball teams five years before he would break the major league’s color barrier as a member of the Brooklyn Dodgers. Jackie would also benefit from Joe’s mediation in a smashmouth incident which would otherwise have resulted in certain court martial wherein Robinson viciously assaulted a commanding officer who referred to him and a fellow black soldier as “nigger”. Louis also successfully petitioned Truman Gibson, JR., the African American assistant to Secretary of War Henry Stimson, on behalf of Robinson and fourteen other black men whose applications to attend the Officer’s Candidate School had been denied.

One additional requirement of his service was Joe’s participation in two propaganda films. 1944’s The Negro Soldier, helmed by Mr. Smith Goes to Washington and It’s a Wonderful Life director Frank Capra, utilized footage from Louis’ demolition of Max Schmeling to patriotic effect in answer to the widespread German distribution of highlights from the first fight. While filming the musical comedy This is the Army for Warner Brothers in 1943, Louis was being fought over by Lana Turner and Lena Horne, resulting in a torrid affair between Joe and Lena which ended badly. After a particularly nasty spat, Louis admits that “I hit her with a left hook and knocked her on the bed. Then I jumped on her and started choking her.” The intervention of Horne’s aunt alone may have saved Lena’s life and Louis from a manslaughter conviction. “I was so scared I was shaking,” Joe continues. “I got chills because I realized I could have committed murder. I had never known such a feeling. I’m not that kind of person. Passion can mess you up.”

The War Department sent Joe out on an exhibition tour where he was reunited with Sugar Ray Robinson whom he had first known as Walker Smith Jr., the youngster from the same Detroit block who would dutifully and cheerfully carry Louis’ duffel bag to the gym. Walker and Joe both lived in an area of the Motor City referred to locally as Black Bottom. “Black because that’s what color we were,” explained Robinson in his autobiography Sugar Ray. “Bottom because that’s where we were at.” While passing through Camp Siebert in Alabama, Louis and Robinson were waiting for a bus and ordered by a military policeman to relocate to the Coloreds Only depot. Unaware of who the Brown Bomber was and undeterred by Louis’ argument that he was wearing the same uniform and serving the same Army, the MP apparently prodded Joe in the ribs with a wooden club followed by the warning, “I’ll do more than touch you, nigger.” Big mistake. “Two Ton” Tony Galento, in addition to making the vow to “moida the bum”, had called Louis “nigger” and received 40 stitches as retribution although Joe confessed to being disappointed that it hadn’t been more. Before Louis could load up his right hand, Sugar Ray jumped onto the offending MP’s back as Joe fought off his two partners. Another military cop responding to the scene recognized the heavyweight champion and the ruckus was resolved without further incident.

Negotiations between Mike Jacobs’ Twentieth Century Sporting Club and Secretary of War Stimson for Joe Louis and Billy Conn to fight for the Army Relief fell apart due to the complexities  regarding payments and deferments which conflicted with “the standards and interests of the Army”. The two did bump into one another (literally) on a London-bound bomber which was experiencing trouble deploying its landing gear, making for 45 minutes worth of anxious moments between two fellow combatants who had already had their share at the Polo Grounds in 1941. Leading on two scorecards and dead even with the heavyweight champion on the third going into the thirteenth round, Conn continued to aggressively press the advantage and was summarily knocked out, causing him to afterwards give the following self-deprecating response to an inquisitive sportswriter: “What’s the point of being Irish if you can’t be stupid?” During the course of their 1944 trans-Atlantic crossing, Billy asked Louis, “Why couldn’t you have let me hold the title for six months? I would have given it back to you.” To which Joe replied with a chuckle, “Billy, you had the title for twelve rounds and you couldn’t hold it. How in the hell were you going to hold it for six months?”

regarding payments and deferments which conflicted with “the standards and interests of the Army”. The two did bump into one another (literally) on a London-bound bomber which was experiencing trouble deploying its landing gear, making for 45 minutes worth of anxious moments between two fellow combatants who had already had their share at the Polo Grounds in 1941. Leading on two scorecards and dead even with the heavyweight champion on the third going into the thirteenth round, Conn continued to aggressively press the advantage and was summarily knocked out, causing him to afterwards give the following self-deprecating response to an inquisitive sportswriter: “What’s the point of being Irish if you can’t be stupid?” During the course of their 1944 trans-Atlantic crossing, Billy asked Louis, “Why couldn’t you have let me hold the title for six months? I would have given it back to you.” To which Joe replied with a chuckle, “Billy, you had the title for twelve rounds and you couldn’t hold it. How in the hell were you going to hold it for six months?”

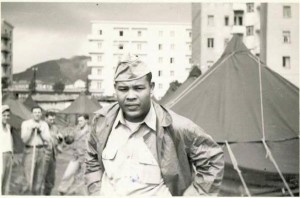

Louis’ globetrotting tour of duty would take him through England, Scotland, Ireland, Italy, and Africa. By his estimation Joe had traveled over 70,000 miles, was seen by 5 million servicemen, and been in 96 exhibition fights. Now aged 32, Joe Louis was honorably discharged on October 1, 1945 at Camp Shanks in Orangeburg, New York in a ceremony during which Major General Kells awarded Joe the Legion of Merit Medal “for exceptionally meritorious conduct”. Joe would reprise his role while war was being waged in Korea five years later, shaking hands and sparring with servicemen stationed in Japan.

Uncle Sam, however, was far from done with the Brown Bomber and would use that bony finger pointing menacingly from recruitment posters to pick the pockets of its American hero.

[si-contact-form form=’2′]