3 British Fighters Who Changed the Face of (British) Boxing in My Lifetime

“Keep your guard up! You’re in a real fight now!” – The Cornerman

Over the din of the crowd the cornerman shouts advice to his boxer on the stool in front of him after another punishing round. He works on his charge feverishly trying to restore his energies and remind him of the gameplan. But the opponent in the opposite corner is no ordinary fighter. The bell rings for the next round and the cornerman’s fighter stands up. He knows he’s fighting on borrowed time. He doesn’t have much left to give. The maelstrom continues. Everything goes dark. Silence inside. Bedlam outside. He didn’t see the shot that put him down and out.

When an opponent can separate you from your senses with one punch as Nigel Benn and Naseem Hamed were capable of doing, or never gives you a moments rest as he applied a relentless body attack as Ricky Hatton did, there’s no time for posing, thinking too much, or looking good behind a low punch output. They made you fight! And you were damned if you did and damned if you didn’t.

The British boxing scene caught fire with the emergence of Benn, Hamed, and Hatton. They were able to raise excitement to new levels and attract the general British sports fan to watch boxing in unprecedented numbers. They also happen to be three of the best fighters to come out of the British Isles in the last 30 years.

For my money the knockout has got to be the most exciting moment in all of sports. And all three fighters delivered countless highlight reel KO’s to keep the fans coming back for more.

Hatton fought with the intensity of a football hooligan during a Manchester football derby weekend.

Benn went after his opponents like a lion who hadn’t eaten a good meal in a long while.

And Hamed had fighting style and rhythm which seemed to be linked to a 90’s dance soundtrack playing in his head.

On the back of all of this boxing’s popularity in Britain exploded. These were heady times.

Arguably there have been better British boxers who have graced that square of illuminated canvas within the ring.

In the gilded annals of British boxing there have been better pure boxers (Howard Winstone, Ken Buchanan, Chris & Kevin Finnegan, Herol Graham), fighters who hit just as hard (Tony Sibson, Colin Jones, Pat Barrett, Roy Gumbs, Neville Meade), pugilists who also fought with reckless abandon (Dave Green, Charlie Magri, Mark Kaylor, Jimmy Flint), and hard men who came to grind their opponents to dust on the millstone of their toughness and ability to ignore all pain (Tommy Farr, Clinton McKenzie).

But none were more exciting or inspired as much passion – love and hate – among fans and pundits alike as Benn, Hamed, and Hatton did.

With their unique contributions they brought British boxing back into the mainstream of public consciousness at home, and won respect abroad on the international scene by taking on the very best fighters in the world. All three are now retired and their career trajectories are etched in stone. But what was the essence of their appeal to fans who followed their exploits? Let me take you back.

36-1, 31 KO’s

Featherweight

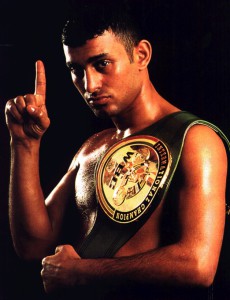

The “Prince” was a promoters dream. Flamboyant, flashy, super confident – some would say arrogant – Naz, as he was called by his brothers and fans, was gifted with natural talents bordering on the sublime. Mechanically and technically he seemed to break all the boxing principles. He was as pure a puncher as you’re ever likely to see. He shouldn’t have been able to hit like a cannon but he did. A prodigy of Brendan Ingle’s Wincobank Gym in Sheffield, an area where no one was discussing the merits of the Hollandaise Sauce with their main course in pretentious Michelin starred restaurants because they weren’t any. It was a working class city, a former steel town who’s heavy industry was a thing of the past and it was struggling to reinvent itself. As a kid you wiped your nose with the back of your hand, played football and supported the local football teams – United or Wednesday – and you boxed.

There was an added air of theatre to Naz’s fights. It attracted the fans. The grand ring entrances, the pyrotechnics and dancing, and the acrobatic back flip over the top rope became his signature move.

Before a single punch had been thrown in anger fans were going to be entertained. Every time. It made them feel part of the event as opposed to being on the edge of it looking in.

Let it be said that a lot of people paid good money to see Naz lose. His arrogance offended some people’s sensibilities.

In 1995 when he went to Wales to fight WBO featherweight champion Steve Robinson in front of thousands of partisan fans I don’t think there was a single Naz supporter in the whole stadium apart from his own cornermen.

It didn’t stop him from wriggling his hips, leering at the champion through his gum shield, and making Robinson miss by swaying his upper body from the waist like a bamboo sapling in the wind. No matter how hard he tried Robinson, a good fighter, couldn’t hit him. But Naz’s retaliation was swift, spiteful and punishing. He beat the noble resistance out of Robinson by the 8th round and you could’ve heard a pin drop.

The Welsh, a proud nation with a long tradition of great champions, were none too pleased.

The Naz bandwagon was well and truly on its way. Two fights later against Daniel Alicea his gold hassled trunks sported the logo of the Adidas global sports brand. The Sheffield court jester had arrived in the mainstream consciousness. And he kept winning in spectacular fashion.

Tom Johnson, America’s IBF Champion, was dispatched in brutal fashion by an uppercut in 8 rounds.

The band wagon played on and more and more people fell in behind it to get a closer look at the goings on and soak up the party atmosphere. HBO jumped on board too, bringing Hamed stateside to fight Kevin Kelley in New York City. For the “Prince” to become King he’d have to conquer America. In one of the greatest debut fights across the pond a British fighter ever made Hamed and Kelley traded six knockdowns between them, three apiece, until Hamed’s power punching settled the argument for good.

Nowadays people are quick to criticize Hamed because of his non showing against Mexican warrior legend Marco Antonio Barerra, who completely outboxed and outfought him in Las Vegas in 2001. “No heart,” they say. Yet he climbed off the canvas on several occasions to knockout the opponent who deposited him there. Daniel Alecia, Kevin Kelley, and Augie Sanchez were all dispatched in devastating fashion. No heart? Nonsense. He had plenty.

42-5-1, 35 KO’s

Super middleweight

“The Dark Destroyer” had one of the best nicknames in the business. And Nigel Benn lived up to it in every way. A dark, thickly muscled, brooding ring presence, Benn was the king of bash. Possessing frightening power he crushed his opposition with either hand. A proud Londoner and former soldier who served in Northern Ireland he was laid back outside the ring but ferocious once he laced up the gloves. Fans love a fighter who takes no prisoners and Benn didn’t take any destroying his first 22 opponents all inside the distance in highlight reel fashion.

Benn would back his man up with steady forward pressure and detonate a right or left handed bomb on the opponents chin. Game over. And the power was real. Very real. Men went down like chopped trees or as if they’d been shot. It was an all or nothing approach which the fans loved. Benn represented that certain British spirit the undercurrent of which even in this age of political correctness still exists.

Encapsulated into a single phrase it would be expressed thus, “A pint and a punch up.” Benn fought in a manner which Brits understood. Minus the booze of course. “Get in there son!, ” Fans would shout while pumping their fists into the air in a show of rabid support. And Benn obliged. Seeking to wreak havoc on his opponent with hammer like blows in the shortest time possible. Yes, there were times when his balls to the wall approach backfired. Slicker boxers were sometimes able to blunt his destructive slashing attacks. Michael Watson was the first to do so in Benn’s 23rd bout, boxing and countering beautifully on a night in Finsbury Park, London, to hand Benn his first professional loss via 6th round stoppage.

A few years later Chris Eubank, Benn’s eccentric arch rival was able to do the same, albeit in a different manner. There was no love lost between the pair in the lead up to their first unforgettable tear up at the NEC in Birmingham. All hell broke loose for nine savage rounds. Both men tried to rip each other’s hearts out. But Eubank surprised everyone with his resilience, outlasting Benn down the stretch to force a ninth round stoppage victory. Benn cried real tears that night when the referee stepped in to save him from further punishment. To lose to someone he despised (at the time) was more than he could bear. We felt his pain. Benn always fought with such passion. He personified the British fighting spirit. And we love him for it.

45-3, 32 KO’s

Junior Welterweight

Manchester should be rightly proud of their native son’s achievements. Ricky “The Hitman” Hatton is a local lad who did good. Very good. He was the everyman through which his fans could imagine themselves performing heroic deeds against all odds. He loved his beer and drank in the same Manchester pubs as they did. He ate the same food and supported the same football team – Manchester City – as half the city did. Even the rival fans from the other Manchester team came out to show their love and support for him when he climbed through the ropes to fight. He had that kind of appeal to the masses. The fact he would gain so much weight between fights – up to 40 lbs -endeared him even more.

Ricky Hatton was his demographic. A pint, a pie, and a game of darts. He grew fat between fights but it didn’t matter. He’d transform himself into a superbly conditioned warrior when it was time to do so. When he fought his fans would make so much noise you could barely hear what the TV commentary team were trying to say. No British fighter in recent memory has had that kind of fanatical support behind him. Hatton seemed to draw his energy from it and he applied a relentless pressure on his opponents causing all but the very best of them to wilt under its sheer force. His body attack was ferocious. Most could not weather it. And his work rate would leave opponents gasping after a few rounds and on the verge of being overwhelmed.

When Hatton challenged the dangerous big punching Russian world champion Kostya Tzsyu, one of the best pound for pound boxers in the world, few gave him any real chance of winning. However, his promoter managed to secure home advantage and anyone who has been to Manchester will tell you that was half the battle won. The lad next door transformed himself once again from a fat, beer drinking, football fan into “The Hitman,” and the whole of Manchester came out to back him.

They were him. And he them. The intensity of Hatton’s marauding offensive slowly wore the champion down. Round by round Hatton’s swarming pressure and body attack drained Tzsyu of all resistance. No matter what he did he couldn’t keep Hatton off him, couldn’t create the space to work to his own strengths. The atmosphere generated by Hatton’s supporters must have taken its toll too in some odd psycho-physical way. The champion began to tire and weaken and by the end of the 11th round he could no longer continue. The Manchester faithful roared. Their everyman had stuck his head in to the lions mouth and extracted all its teeth.

Hatton would go on to fight and lose to the two best fighters in the world in Floyd Mayweather, JR. and Manny Pacquiao. But the Manchester hordes would be right there with him on American soil literally singing his praises even in defeat. The American’s had never seen anything like it. But British boxing fans are a special breed. They’ll keep their sense of jolly humor even in the face of adversity. Union Jack flags draped over their shoulders, with beers in hand. There’s always time for a song.

[si-contact-form form=’2′]