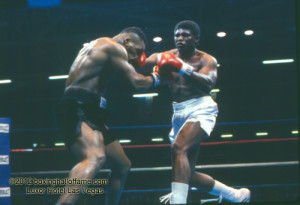

Mike Tyson: Just How Great Was He? James “Quick” Tillis & Buster Douglas Changed Boxing History for the Once Baddest Man On The Planet!

By Andrew “Drew The Picture” Hames

By Andrew “Drew The Picture” Hames

Photo Credit: Boxinghalloffame.com

December 27, 1985 marked a very telling moment in boxing history to me, if not to most… It was the day when a rising prospect in the sport named Michael Gerard Tyson squared off against a fighter by the name of Mark Young on a program called “Friday Night Ringside”. Tyson was 14-0 at the time, with all his victories coming by way of emphatic knockouts that had the boxing world buzzing about a fighter many projected to be the next dominant world champion ever since his pro debut on March 6 of this same year, when he’d blasted out Hector Mercedes in one round, displaying an other-worldly blend of speed, power and inside technique along the way…

The opponent Mark Young was less than sensational, bringing with him to the ring an early pro record of 12-4-1, with 8 KO’s. The Charlotte, North Carolina-based young, apparently aware of the early devastating reputation Tyson had developed as an attacker apparently decided that his 8 KO victories in 12 wins and the lack of opponents who’d ever actually looked to apply pressure to the young Tyson offered him his best chance of pulling the dramatic upset… Uncharacteristic of Mike’s opponents up until that point, Young attacked from the opening bell until the very end of the fight. The unfortunate part for Young was that the very end of the fight came 1:15 seconds later, in the very first round, virtue of a punch that virtually no one ringside had even seen land, least of all Young, who was literally sent off his feet, across the ring and into the ropes before arriving at his final destination, which was an all-expenses-paid, face first class trip to the canvas…

Conventional boxing wisdom has always taught in essence that it is impossible to accurately determine whether a fighter is good or great by how he looks when everything goes his way, and his opponents offer him very little resistance to warrant the deployment of a Plan B. In this scenario, a sensational attacker would be proven to either be good or great by how he responds while being attacked himself. If nothing else, Young’s boldness provided the first glimpse into the overall make-up a Young Tyson’s pedigree, reserve, resolve and potential, even if only for a brief, fleeting moment….

Instant replay told a somewhat contrasting story however, of an extremely nervous Young, looking to attack perhaps more out of the fear of facing the potential consequences of allowing Mike to initiate the action than any form of confidence or intellect behind his aggression, nearly telegraphing every single punch he threw, and getting badly off-balanced with a recurring one two followed by a wide and partially slapping left hook. With the utmost respect for Young for his boldness to take on a reputed destroyer like Tyson who’d stopped 14 opponents in the first place, it was almost reminiscent of an amateur’s first fight with a live opponent, or the nervous windmill-like flurrying that one would expect to see a female employ in a street fight. Tyson remained poised and grew wise of this pattern quickly, turning southpaw for a split-second as Young got off balance over missing what would be his final one-two attempt, as he was lifted off his feet from a short right uppercut that appeared to render him unconscious some time between realizing it had landed and officially touching the canvas. While seemingly insignificant, this fight proved to be quite pivotal for the kid with the thunder bolts in his fists fighting out of Catskill, New York, because while Young was obliterated, he did provide a small doorway for better coordinated fighters to follow in terms of confronting Mike’s aggression, marking the first time a fighter chose to engage him from the opening bell, while at the same time showing that even aggression could be spawned out of fear…

As Mike continued to climb the prospect ladder in 1986, his legend in the sport was already taking on monumental status. His legendary trainer Cus D’mato, along with cornermen Kevin Rooney and Teddy Atlas, spoke superlatives about the kid who’d walked into their gym at only 12 years old, weighing 190 pounds, with zero body fat. He was a scary blend of modern athleticism mixed with old-school rudiments, and a tenacity rarely ever seen before. It was said that he possessed the power and ferocity of a Joe Louis or Sonny Liston, accompanied by the infighting of a Henry Armstrong, the bobbing and weaving pressure of a Joe Frazier, and the combination-punching of a welterweight. The legend was beginning to grow already….

At this point, Mike’s journey of destruction had become so vaunted that his 1986 campaign began with a fight against Irish Heavyweight Mike Jameson, in which, in reverse to the traditional 3-minute clock winding down from the beginning till the end of a round, the amount of bets placed on how quickly Mike would dispose of Jameson resulted in a stopwatch-like clock being shown on the bottom right corner of the screen going forward to time the exact time Jameson would fall. To Jameson’s credit, his veteran savvy, toughness, underrated counter-punching and holding techniques prolonged his demise all the way to the 5th round, even after surviving a knockdown in the 4th, and much to the dismay of the odds-makers banking on the KO coming much longer. Jameson was a fairly under-appreciated journeyman fighter himself, having went the distance with Randall “Tex” Cobb and fighting to a split-decision loss against a prime Michael Dokes. His fight with Tyson also marked the last time that stopwatch-like round-timer was ever used in a pro bout…

Tyson then went on to fight former world title challenger Jesse Ferguson, who was coming off a competitive KO loss to Carl “The Truth” Williams, and had won a war with James “Buster” Douglas earlier in the year in route to winning ESPN’s 1985 Young Heavyweight tournament. Ferguson went on to shock considerable favorite Ray Mercer in a fight scheduled only to set Mercer up for a title fight with Riddick Bowe, which went to Ferguson in a disappointing second-round KO. He’d mark himself in this Tyson fight to be Tyson’s first chippy affair, occasionally fighting after the bell, and scoring just enough solid blows to assert his own presence in the fight before succumbing to Mike’s pressure and being disqualified for holding in the 6th round, technically snapping Mike’s consecutive KO streak and becoming the first fighter to take Tyson into the 6th round, directly after Jameson had become the first to take Mike to the 5th a mere fight before.

Likely for publicity’s sake, Ferguson’s disqualification loss was written off as a KO defeat, which extended Tyson’s record going into his fight with tough journeyman Steve Zouski, a bout in which Mike dominated as usual, but ate some unexpected leather and faced some unexpected resistance in doing so, prompting Mike to grade himself with a C for the overall performance, although continuing his KO streak along the way, never allowing Zouski to see the second half of the fight…

Before the memorable Douglas upset, and even before Mike going on to become the youngest Heavyweight champion in history (a record formerly held by former world champion and Cus D’mato fighter Floyd Patterson) and the first fighter to hold three Heavyweight titles simultaneously, came his fight with former amateur standout, title challenger and proven formidable foe James “Quick” Tillis, who would effectively snap Mike’s KO streak at 19 and become the first fighter to ever go the full 10-round distance with Mike, as well as using his quick hands and guile to become the first fighter ever to be credited with winning a couple rounds against the seemingly invincible young phenom, albeit in a losing effort…

Perhaps the greatest irony of this story was that the first fighter to ever take Mike the distance had developed a reputation for fatigue issues late in fights in Tillis, who’d already endured losses to Mike Weaver, Tyrell Biggs, Tim Witherspoon, Pinklon Thomas and others prior to their showdown happening that late in Tillis’ career. Meanwhile, Douglas, the first fighter to actually defeat, dominate and KO Tyson, entered their fight with a reputation for coming up short in his biggest fights, poor training habits and questionable resolve, coming in 20 pounds heavy to be knocked out in the second round against David Bey, being stopped in the 9th round of a fight he was otherwise dominating against Mike White, dropping a majority decision to Jesse Ferguson, and running out of gas to essentially be stopped in a fight he was ahead in against Tony Tucker. The idea that Tillis and Douglas offered Tyson his greatest resistance early in his career serves as a testament to how styles and circumstances make fights far more than a reputation or a resume ever will…

For the sake of summarization, we’ll forego the remainder of Tyson’s illustrious career until next time around. But I believe this particular series of fights simultaneously showed us what made Mike great and why he never achieved the longevity generally associated with greatness. Tyson showed why he was always dangerous and justified the intimidation most fighters seemed to endure when they faced them. He also showed us why no fighter was and ever will be invincible. I remember hearing Tyson’s former manager Bill Clayton once say that they initially intended to build his record up to about 40-0 before placing him in a world title fight. Fortunately for us, and his record as the youngest Heavyweight champion in history, it came much sooner. But a sad underlying factor in this story is that as his competition slowly improved, so too did the resistance of his opposition. I’ll never forget the cold chill of reality I felt on February 11, 1990. To be continued….

Signing off until next time….

[si-contact-form form=’2′]