Dwight Muhammad Qawi and Michael Spinks Unify the Light-Heavyweight Title in “The Brawl For It All”

By Chris “Man of Few Words” Benedict

By Chris “Man of Few Words” Benedict

Although it was arguably one of the fight game’s most exciting and talent-rich eras, the early 1980s also found boxing in the midst of a severe identity crisis, one from which it has never recovered. The formation of new governing bodies, augmented by the addition or modification of a growing list of weight divisions and their accompanying profusion of title belts, only added exponentially to the confusion often likened to alphabet soup out of which your spoon emerges from the bowl in a schizophrenic jumble you are at a total loss to make much coherent sense of. In the winter of 1983, boxing had only one undisputed champion, Marvelous Marvin Hagler who reigned supreme in the middleweight division.

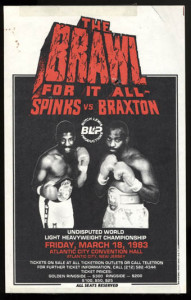

As the approaching Vernal Equinox promised longer, brighter, warmer days to come, so too did the March 18th title unification bout between WBA champion Michael Spinks and WBC belt-holder Dwight Muhammad Qawi offer a glimmer of hope for boxing’s sadly bastardized light-heavyweight class. Not since the short-lived retirement of the great Bob Foster in September 1974 had there been a singularly recognized light-heavyweight champion, Victor Galindez and John Conteh having succeeded Foster as representatives of the WBA and WBC respectively. Dwight Qawi, having forcefully snatched the WBC belt away from Matthew Saad Muhammad in December of 1981, Michael Spinks, who put the jinx on WBA champion Eddie Mustafa Muhammad five months prior to that, and promoter Butch Lewis sought to alter the fistic landscape for the better.

Lewis convinced Qawi, who had officially announced the changeover to his adopted Islamic name four months earlier, to go by the more recognizable Dwight Braxton for its added “promotional and marquee value”. It evidently made little difference in regard to the abysmal advanced ticket sales which accounted for only slightly more than half of the Atlantic City Convention Center’s 14,000 available seats. If Lewis, Michael Spinks’ business manager and promoter and big-brother figure (which must have been irksome to Leon), was sweating through his all-white shirtless tuxedo and hoping that walk-up sales would round out the difference, an unfortunately timed thunderstorm further dampened his spirits though he naturally hid it behind his ostentatious façade. The total attendance of 9,854 fell short of a $1 million gate which meant that it-and the lackluster foreign television buys-would barely cover the Convention Center’s rental fee without even taking into consideration each fighter’s guaranteed $1.2 million purse. But, even if Butch would take a financial bath on his “Brawl For It All” brainchild, he was well aware that a unified title to Spinks’ credit-not to mention vanquishing the division’s feared boogeyman in the process-would bring in its wake more lucrative opportunities, such as an eventual climb up the scales to challenge the likewise undefeated heavyweight champion Larry Holmes.

For Braxton and Spinks, the stakes were more personal than financial. They had spent more than a year taunting each other in newspapers and magazines and from ringside seats at one another’s fights, Dwight developing the pet name Michael “Stinks” Spinks for his nemesis. Spinks had employed Braxton as a sparring partner in 1980 while training for David Conteh and Dwight described Michael as “safe, methodical, sneaky”, but added that “I was eating him up every day.” Not surprisingly, Michael’s recollections differ significantly as he said retrospectively and, as things would play out, somewhat prophetically, “There were a couple of times I jabbed him to death for eight or nine rounds.” The Spinks team had tapped into the genius of Eddie Futch who devised the training strategy that Michael would execute during the fight to such stunning effect. If Dwight would show respectful caution or, better yet, preoccupation with the overhand right known as the Spinks Jinx, then Futch would see to it that Michael conjured some magic for the left, infusing it with a voodoo all its own to ward off Braxton’s evil spirits. Spinks also dwelled on Braxton’s failure to settle up on an old $45 loan to buy a radio, causing Dwight to reply with his trademark gallows humor, “I’ll send you the money in a first-aid kit.”

Braxton had been nursing a nasty cold, reportedly bordering on walking pneumonia, for two weeks prior to fight night which his manager Rock Newman suggests was treated by Dwight’s co-trainer Quenzell McCall with a raw egg in a glass of beer, a self-medicated prescription that Braxton then over-indulged in. McCall remembers it instead being a mixture of grapefruit and orange juices along with a shot of penicillin. While Braxton may have been carrying some residual bacterium into the ring, Spinks was burdened with legal problems and a very heavy heart. Michael blew through a red light during a January 5th joyride with his brother Leland through the streets of Philadelphia in his brand new Mercedes, resulting in a high-speed chase with police (depending on whose version you believe) that ended with the discovery of a .45 containing six spent shells on the car’s floorboard. Released after posting a $1,000 bond, the incident would cost Michael an additional $1,770 fine following a guilty plea. Two days after his arrest, Spinks’ common-law wife Sandy Massey was killed in a head-on collision on the Schuylkill Expressway. Braxton, in a display of good sportsmanship and human decency-which, contrary to his prison record and ring persona, were common character traits-sent a floral arrangement to the funeral. An already inconsolable Michael was rendered horrifyingly speechless when his two year-old daughter Michelle bounced into his dressing room and asked in blissful ignorance, “Where’s Mommy?”

The boxing ring offers the fighter an inner sanctum wherein he or she may achieve a cognitive lucidity that proves simply evasive and ambiguous outside of that given realm. Michael Spinks would grab hold of it and rarely let go, after first releasing the manifest frustration and confusion balled up in his right hand which he sent hurtling into the side of Dwight Braxton’s head in the bout’s opening seconds. Braxton retaliated with a right/left combination midway through the first which buckled Spinks’ knees but Michael managed to duck under a thunderous right, sending Dwight reeling into the corner where Spinks pursued and unleashed a largely ineffectual barrage of punches most of which Braxton caught on his gloves or shoulders. It quickly became clear that Michael was following Eddie Futch’s instructions to the letter, using his left jab and five-inch reach advantage to keep Braxton at a safe distance. Unable to get his own jab going, work inside, or put punches together, an exasperated Braxton pounded the back of Spinks’ head as referee Larry Hazzard broke them from a clinch in the third round.

Spinks got creative with the left hand as the fight progressed, following his jabs with hooks or uppercuts which scored with greater frequency as Dwight ponderously held his left arm straight down against his leg. The combatants traded right hands early in the sixth, Braxton wagging his tongue between his mouthpiece before landing a right/left combination that sent Spinks off-balance. A flurry followed during which Braxton landed an effective uppercut but Michael would recover to throw a left lead with a right on its tail, backhanding Braxton to add insult to injury. Leon, who can be seen jumping around the ringside sections wearing an over-sized cowboy hat and screaming encouragement like some berserk cheerleader or jack-in-the-box come unsprung, materialized in Michael’s corner between the sixth and seventh rounds to offer guidance on doubling up the jab and following it with a right, advice which his little brother dismissed with a warning of his own for Leon to straighten out his Stetson.

The eighth was a bizarre round which saw Spinks hit the canvas three times, the second of which should have been ruled a push or slip like the others but came as the result of a glancing body blow and, therefore, ruled a knockdown. Larry Hazzard, particularly after viewing a replay of the incident which revealed Braxton stepping on Michael’s toes, later admitted to having blown the call. Regardless, Dwight lands a crushing right behind three consecutive left hooks as Spinks appears noticeably slower, flat-footed, and back-pedaling away from Braxton who, for the first time, counters effectively with right hands over Spinks’ left hook when Michael does stop to engage. Braxton crouched and crab-walked away from Spinks’ measured punches, causing him to whiff badly over Braxton’s bobbing and weaving cranium. Dwight, who ended the eleventh with a left/right/left combination that rocked Spinks back into the ropes and had yet to fight a twelfth round in his career, began this one literally running after Michael. When he did catch up to him, Spinks unloaded double and triple jabs before eating a hard right before the bell.

Looking tired and head-hunting with single shots almost exclusively not to mention uncharacteristically, Braxton entered the championship rounds at a seemingly considerable disadvantage. Chants of “Michael! Michael! Michael!” reverberated across the Convention Center as Larry Hazzard restrained the adversaries for the customary touching of gloves at the beginning of the fight’s final round, both barreling toward one another the moment Hazzard lifted his arm like the release gate being pulled open at a rodeo. Spinks spent the majority of the fifteenth on his bicycle, stopping to methodically pop the occasional left jab, thwarting any attempted attack on the part of Braxton and putting an abrupt stop to the rallying cries of “Qawi! Qawi! Qawi!” Collapsing into each other’s arms, Braxton and Spinks (who was holding his daughter Michelle in his arms and shouting “I did it! I did it!”) awaited the inevitable recitation of the decision in Michael’s favor, although by a much slimmer margin than had been anticipated. Dwight good-naturedly embraced Spinks while Michael promised him “We’ll do this again.”

“Again” was supposed to have been in September 1984 but, in addition to a recurring shoulder injury, Dwight Qawi’s life became a shambles following a bitter divorce and, worse still, his brother Lawrence’s arrest for the murder of their father Charles. “The Koran teaches that every soul must taste death,” a somber Qawi told Elmer Smith of the Philadelphia Daily News. “Not only physical death. But death is a metaphor. Death to the ignorant is the end. But, to me, it’s a transformation.”

Requesting and being denied a postponement by Butch Lewis, Qawi instead found a new home in the cruiserweight division and knocked out WBA champion Piet Crous on July 25, 1985 at the Superbowl in Sun City, South Africa. This was Dwight’s second controversial foray into the stronghold of Apartheid, the first being a 10th round knockout victory over Thenius Kok in only his eighth professional fight five years earlier. The opponent selected for the first defense of his newly won WBA title was none other than Leon Spinks. A contract with Evander Holyfield’s name already inked onto it awaited the signature of the winner, yet Qawi’s directly related future was focused not on the 1984 Olympic bronze medal winner but on a more familiar gold medalist from 1976, Michael Spinks, who had since tarnished Larry Holmes’ undefeated streak and taken his IBF heavyweight title in the bargain. “If somebody beat my brother the way I’m going to beat Leon,” said Dwight, “I’d want to fight him.”

Leon was struggling through bankruptcy proceedings, escalating alcohol dependency, and the need to shed 23 pounds so that he could make the 190 cruiserweight limit. Rock Newman remembers going through the lobby of Reno’s Peppermill Casino, where both fighters were staying, at 5 am three days before Saturday’s Wide World of Sports featured fight at the Lawlor Events Center to warm up the car that would follow Qawi on his morning roadwork and seeing Leon still up and reveling in the previous evening’s tomfoolery. All things considered, Leon never stood a chance. Qawi pummeled the eldest Spinks mercilessly, backing himself into a corner in the fourth round where he dropped both hands, gyrated his hips, and presented Leon his unprotected jaw in what should have been a fish in a barrel situation had Leon possessed the dexterity to efficiently pull the trigger. Instead, Qawi effortlessly maneuvered his head around each punch which found nothing but air and returned hellacious volleys of clean-landing shots while laughing, poking out his tongue, and yelling at Emmanuel Steward and the rest of Leon’s frantic cornermen to shut up.

When Mills Lane put a stop to the carnage in the sixth, Leon said to a distressed Steward, “Don’t be so damn serious. Let’s go have a drink.” He was subsequently slapped with a 90-day suspension by the Nevada State Athletic Commission after testing positive for Phenobarbital, a depressant Spinks admitted to using for stomach ailments related to his rapid weight loss, during the post-fight examination.

By the time Dwight Qawi bulked up to heavyweight stature, the division was held under the dominion of “Iron” Mike Tyson with whom a visibly unnerved Michael Spinks had a 90-second date with destiny on June 27, 1988. Three months prior to that, a 222-pound Qawi was disabused of whatever notion he may have harbored concerning getting the winner of the anticlimactic Spinks and Tyson “Once And For All” extravaganza at the hands of George Foreman in a sorry spectacle at Caesar’s Palace.

I clearly recall “The Brawl For It All” being a big deal to me as a young kid, who was (and still is) a Dwight Qawi fan, and an even bigger letdown. Whatever reasons Qawi gave for his performance in the fight’s aftermath-fatigued by the pneumonia or suffering from a poorly repaired broken nose (which could be seen leaking blood later in the bout) or referee Larry Hazzard being in Butch Lewis’ pocket-he is still adamant about the fact that Spinks refused to stand toe-to-toe with him. When meeting Dwight at the 2014 International Boxing Hall of Fame inductions, I opened my copy of Michael and Leon’s dual biography “One Punch From the Promised Land” to a page showing a photo from the Braxton/Spinks “Brawl” hoping he would sign it for me and offer his thoughts on that night. He scribbled his name next to his likeness and admitted that the frustration lingers on, saying with a sad little shake of his head that “Michael ran away from me the whole night. I got tired just chasing him around the ring.”

Between the brothers Spinks and Big George Foreman, however, stood Evander Holyfield and he wasn’t running anywhere.

[si-contact-form form=’2′]