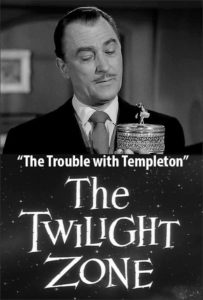

The Twilight Zone Review: The Trouble With Templeton

The trouble with the trouble with “The Trouble With Templeton” is that even though the trouble with “The Trouble With Templeton” is a slightly confusing motivation regarding the ruse, the trouble with that is even after you’ve got the problematic plot twist straightened out, the trouble then becomes, “Was the supposedly beneficial outcome all that beneficial?” Perhaps I’m being a little bit too picky about asking that question. I ask it because at the end of the episode, our lead character is “fixed” and has a newborn burst of super-confidence, which is a good thing mostly, but it did make him seem a little bit douchey, whereas before we had such a warm compassionate feeling for him. My honest opinion was I would much rather befriend the Booth Templeton we meet at the beginning of the episode rather than the one at the end. But I do have to admit, that perhaps the Booth Templeton at the end is the healthier one, emotionally. His prior self was suffering from too much nostalgia, and who knows, his bolstered attitude might pave the way for a physically healthier Templeton who can wean himself off those pills he is given at the beginning by his kindly, well-meaning man-servant.

So then, perhaps it is only the trouble with “The Trouble With Templeton” that is more of an issue and the reason why this episode received only 5 votes in a survey of fans and writers asking, ‘What is your favorite episode of the original Twilight Zone series?’ tying it with 7 other episodes for 117th thru 123rd place of the 156 episodes.”

I would like to start out by saying this is a wonderful performance by actor Brian Aherne. He earns our sympathy from the get-go, lamenting his being at an advanced age. His melancholy is touched with a sense of learned wisdom, and he forges onward as we watch him get dressed, preparing to go to the theatre for the first day of rehearsals of a new play. So, he’s keeping up his appearance, looking dapper, not giving up. We like him as he converses with his faithful valet, Marty. We can tell Templeton must be a good man from the way Marty has such obvious dedication and respect towards him. It’s a very nicely written opening to the show for that reason—establishing an important sense of the soul of Booth Templeton. Brian Aherne pulls it off with precision and honesty, avoiding making him too much of a sad sack. Booth even has the sagacity to know that his much younger wife who dallies indiscreetly outside by the pool with another man, is partly the fault of his own earlier self’s attempt to attain the sense of love he once had with his first wife, a love we learn that he still misses deeply. “Laura” he reminisces, “The freshest most radiant creature God ever created.” Templeton was 18 when he married her, but she died just 7 years later. “There are some moments in life that have an indescribable loveliness to them. Those moments with Laura are all I have left now.” Marty feels so badly for Templeton, and so to his credit Templeton bucks up a bit and with poise, and assures Marty he’s all right.

Templeton arrives to the theatre, late however. His first encounter is with the financial backer, Mr. Sperry who is performed with an interesting sort of oddball imperiousness, by King Calder. He tells Booth that an Arthur Willis has taken over as director of the play. A “boy wonder” as Sperry calls him, Booth enters the theatre and Willis is in mid-speech to the cast assembled for a table read of the play. He sounds like a real tool, a bit over-the-top as an arrogant theatre director as played by the young Sydney Pollock who would become the excellent film director in his later years (“Tootsie”, “Out of Africa”, “Three Days of the Condor” etc.). Though he’s not good year, in fairness I want to give a shout out to Mr. Pollock for actually becoming a terrific actor in his advanced years when he stepped back into that endeavor alongside his directing. He was absolutely spot-on wonderful in his scenes in “Tootsie” with Dustin Hoffman, more than holding his own. And in the comedy “Death Becomes Her” he has a cameo as an ER doctor, and in his one scene with Meryl Streep, I promise you he gets the biggest laugh in the entire movie. So his early still-green performance here is forgiven in my book.

Willis dresses down Templeton for being late, and it throws Templeton off terribly. He isn’t used to receiving this amount of disrespect, especially from someone relatively new to Broadway, compared to Templeton’s having been in 30 plays. Between his young trophy wife carrying on, not so behind-his-back, and getting scolded by a neophyte to Broadway, these affronts to Booth’s already fragile ego prove to be too much. He has a panic attack and bolts out of the theatre. I’m not thoroughly convinced that the character of Templeton presented to us would do such a thing. To me I think a more believable reaction would have been that he would have simply apologized sincerely in a most genteel manner, and would have politely smoothed things over with a kindly offer to get down to business. This sort of solution would have come to him easily, both because he’s an actor, but also just because he’s so well-mannered. But the episode has to fulfill its mission of sending someone to the Twilight Zone, so they had to have him run out of the theatre, and into the street whereupon he is greeted by a throng of theatre devotees applauding him. That’s puzzling he thinks, but it’s not as strange as the theatre poster advertising a play of his from 1927. And strangest of all is when an old fellow comes ambling up and tells him that his wife, Laura, is waiting for him at Freddie Iaccino’s, a night club where he and she used to frequent many years ago. Booth is so taken with the beautiful miracle of this that he quickly overlooks the impossibility of it. With a look of hope and anticipation growing over his face, he hurries to the club.

Inside the club, Booth is surprised to see that Freddie is indeed alive. Booth says that Laura is not at their usual table, which is a nice indication that something’s up, and when he’s shown to her table, she is laughing and drinking with an old mutual friend of theirs Barney Flueger who wrote and directed a play that Booth was in. Spotting her, Booth is mesmerized and then approaches her. Something feels wrong, and we spot it long before Booth does. Laura is cold and distant to Booth, giving just the minimal amount of attention. She dives into her steak with relish, carving it up and savoring its juiciness, offering none of the same enthusiasm to Booth. But she will indeed carve him a broken heart. She chides him, “Oh Booth how many times have I told you to take your make-up off before you come in here?”

Booth tries to get Laura to come leave with him and be alone with him to talk. “Booth don’t be dull” she says. Booth professes his love and how he wants to take advantage of this miracle while he still can, but she just takes out her compact and tweaks her make-up. Hardly seems like the type of woman Booth described to Marty. Booth tries to get through to her, but Laura just fans herself with some papers. Frustrated, Booth grabs them from her, seizing her attention to explain, “Laura, something’s happened.” He tells her that he’s not wearing make-up, he’s grown older “in another world” and that “for many, many lonely years, I’ve had only a memory of you to live on.” He brightens up with, “And now tonight, or today, or whatever it is, and wherever I am, in space or time, I have you back again. You’re alive! You didn’t die! Life is going on here.” But Laura is not sharing the excitement. She looks instead like she’s barely tolerating his blather. He calls her on it, and she blurts out “Well what did you expect?” He pleads, “But you were my love.” He reminds how everyone who ever saw them together could tell how in love they were. Laura and Barney both laugh at Booth, frustrating him cruelly. He takes her by the hand to try and leave with her—perhaps getting her out of this club can restore her to her former self. But she resists and comes out with it: “You’re a silly old fool of a man!”

She breaks away from him and starts dancing the Charleston, almost insanely. Booth grabs her again, but she slaps him right in the kisser. “Why don’t you go back where you came from? We don’t want you here” she scolds. Hmm, is that an admission that she knows what’s going on, alternate universe-wise? She goes back to her flapper dance as the musicians continue blaring their tunes. Booth is stricken. He leaves hurriedly before the pain of this gets any worse. And as Aherne passes by the camera, cinematographer George T. Clemens and director Buzz Kulik pull off an effective trick. The music suddenly stops, the full crowd falls silent, and the lights dim. The camera pans over to Laura, the only one lit, and she takes several steps forward facing us dead-on. She too now, looks heart-broken.

Booth emerges out onto the street and back to the theatre where he was supposed to rehearse earlier. Things seem back to present time. Booth is sweating after his experience and to fan himself, he pulls out the papers he snatched away from Laura. But he notices that the papers are a script titled, “What To Do If Booth Comes Back.” And herein lies the trouble. He reads it and discovers that it is a script that details the entire event back at the nightclub exactly as it happened. The dialogue is the same, the actions, everything. Booth’s eyes glisten with joy as he realizes, “Acting. They were acting for me!” The episode’s writer E. Jack Neuman clumsily has Booth spell it all out for us aloud, “They wanted me to go back to my own life. And live it.”

Laura and Barney needed a script to do that? And another thing, how did the script predict what Booth would say, and thus have the proper response written for Laura and Barney? And why resort to such a cruel method? Why couldn’t Laura and Barney just talk with him and tell him to live his life fully, and then bring the flashback to an end. It feels terribly mean to even leave Booth with the notion that Laura was a horrible person—it would destroy Booth’s memory of her.

So Booth is back, enlightened. Just in time for an awkwardly acted denouement with Arthur Willis. But Booth is no pushover this time. He lets Willis know that he is to be called “Mr.” Templeton, and he insists that Mr. Sperry leave, because he doesn’t allow anyone else on set during rehearsals. Booth is professional and no-nonsense. The camera pulls back as Booth goes about greeting the rest of the cast as they all start to get ready to rehearse.

And this critic rates this episode a 5. No encore.

[si-contact-form form=’2′]