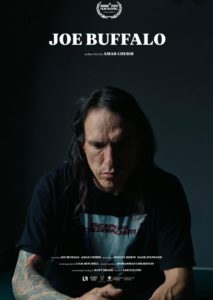

In The Short Film Documentary Joe Buffalo, Viewers Get To See The Lasting Effects Of Residential Schooling On Canada’s First Nation People

In 2021, the world was shocked when the remains of hundreds of indigenous children were found in unmarked graves at multiple sites of government run residential schools in Canada. How did this happen? How did they go unnoticed for so long? What went on at these schools that led, not only to the deaths of children in the care of those running the schools, but why weren’t they returned to family?

In the short documentary film Joe Buffalo, indigenous skateboard pro and legend of the same name, gives us a glimpse into the horrors faced by those sent away to these schools. A descendant of Chief Poundmaker, who Buffalo describes as the Mahatma Gandhi of his people, Joe has spent the past three decades carrying the painful memories of his time at residential school. One that nearly destroyed him and almost kept him from his dream of becoming a professional skateboarder.

Inspired by his cousin Mario, Joe knew at an early age that he wanted to skateboard. Hanging with the older kids, he would skate and practice with them in the hopes of getting their approval. Spending countless hours practicing his ollie. But that dream would be interrupted when at the age of 11, he was removed from his home and family and shipped off to residential school. It wasn’t a surprise. From his grandmother to his parents to his siblings, residential school was a fact of life for First Nation children.

While Joe didn’t experience the sexual abuse his father did, the years Buffalo spent in residential schooling was no less painful. He tells of 250 children in a room. Bunk beds floor to ceiling. There was little to no communication with his family and he got to see his parents only once or twice a year. Constantly being told that he was worthless and inadequate, and the culture that gave him identity and pride was not good enough. By 9th grade, Buffalo left residential schooling and moved with his family to Ottawa. He began to focus solely on skateboarding and it wasn’t long before the teenager garnered the attention of pros and sponsors.

But low self-esteems coupled with the unaddressed pain and trauma of his experiences at residential school, kept Joe from realizing his potential. He rebuffed offers of going pro and engaged in behaviors that saw sponsorship offers dry up. A cycle of drug and alcohol abuse would eventually lead to incarceration. This only made things worse. Confirming in his mind what he had internalized for years, that he wasn’t good enough. Suicidal thoughts and multiple drug overdoses would lead Buffalo down a dark path he knew he couldn’t, didn’t want to, sustain.

internalized for years, that he wasn’t good enough. Suicidal thoughts and multiple drug overdoses would lead Buffalo down a dark path he knew he couldn’t, didn’t want to, sustain.

Embarking on a journey of self-discovery, acceptance and acknowledgement, Joe Buffalo would eventually confront his past and fight to move past it. Not wanting to be a statistic, a stereotype or continue the intergenerational cycle of hurt and hopelessness.

In 1894 the Canadian government began a residential school system for indigenous children. “Kill the Indian, save the child.” Assimilation by indoctrination and Christian re-education. The schools were intentionally located far from indigenous communities, making it extremely difficult for parents to see their children. The parents could also choose either day schools or industrial schools but most lacked the resources to get the children back and forth and meet requirements so they reluctantly sent them to residential school.

The implementation of passes further restricted parents’ access to their children. It was a way for the government to regulate and monitor the movement of First Nation people on and off the reserves. If a parent did not speak English, they were denied visitation. And residential children were forbidden to speak their native languages or engage in any aspect of Native culture or customs. If they were caught violating these rules they would be forced to eat soap or beaten. Or both.

Stories of abuse led parents to resort to desperate measures like hiding their children. Their questions and concerns were dismissed and ignored as First Nation children were rounded up on the reserves, forcibly removed from their homes and sent to residential schooling despite parental objections. By keeping the families and children separated and limiting communication, the children became even more isolated. When they did return home, they had lost their language and their re-education created barriers with the community they once belonged to.

It’s been reported that over 150,000 First Nation children were sent to residential schools in almost a century of operation. Between 1894-1947, attendance was mandatory. Thousands died in the custody of the government and church run institutions and thousands would never be heard from again. Most schools had cemeteries on site. In 2015 according to the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, who investigated the deaths and disappearance of thousands of indigenous children, the Bureau of Indian Affairs refused to return the childrens’ bodies to their parents. And that what happened at these schools amounted to cultural genocide.

While 4120 deaths were recorded, the discovery of over 1300 unmarked graves at just four of the 139 residential schools has cast doubt on the validity of that number. With the TRC speculating that it could be at least double. Especially since more details of the conditions and treatment of First Nation children at those schools has been made public.

By the ‘90s, more and more students came forward with their experiences. Stories of sexual and physical abuse, harsh discipline, malnourishment and overcrowding. Forced labor and psychological abuse. Nutritional experiments that led to malnourishment and other lasting deficiencies. Told through the memoirs of former students still coming to grips with the horrors they endured. Female students were domesticated, and male students militarized to uphold and indoctrinate them to a colonial patriarchal belief system. By 1997 the last government run school, Kivalliq Hall in Rankin Inlet closed. Closed by not forgotten. Wounds that never healed.

The documentary Joe Buffalo shines a light on the lasting effects that residential schooling has had on First Nation communities across the country. Traumas passed down. Violence, sexual abuse, mental illness, drug and alcohol abuse. High suicide rates and half of those forced into residential schooling have criminal records. 65% have some form of PTSD and over 1/3 continue to suffer from major depression. Those just like Buffalo. Though Joe was able to confront his demons, getting sober in 2017, many more have not reached that point.

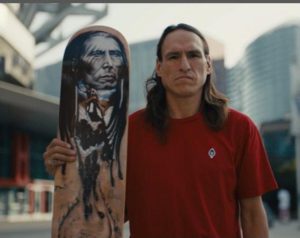

Joe Buffalo finally realized his dream of going pro with Colonialism Skateboards. He co-founded Nations Skate Youth with fellow indigenous skateboarder Rosie Archie. A non-profit that brings skateboarding to reserves and indigenous communities to inspire and empower youth like 24-year old Tik Tok sensation Naiomi Glasses. A female Navajo Nation skateboarder from Rock Point, Arizona. She dreams of seeing a skate park built on Native lands.

It is Archie’s dream to create something in Canada similar to the All Nations Skate Jam held annually in Albuquerque, New Mexico. Around the same time as the annual Gathering of Nations Pow Wow, also in Albuquerque. Where over 565 tribes from the United States and 220 from Canada are represented. Celebration and preservation of culture, community and language. For 11 years shoemaker Vans has been a partner and sponsor of All Nation sSkate Jam and The Skate Witches provide free shoes and boards to indigenous youth.

As the only known survivor of residential schools to go pro, Joe hopes to not be the last of First Nation and indigenous people to break the cycles of intergenerational and systemic abuses. To let his people and others know that the past doesn’t have to be the future.

Check out Ty’s book THE POWER OF PERSPECTIVE. It’s a collection of affirmations she wrote to get her through a difficult time in her life. Words of wisdom that apply to anyone, and everyone, to get through the hard times. If you’re questioning yourself, and need a reminder that you are in control… Click HERE to order your copy.

[si-contact-form form=’2′]