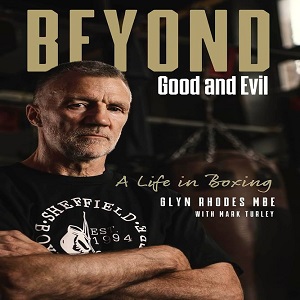

RSR Book Review: Beyond Good and Evil by Glyn Rhodes with Mark Turley

Book review by Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

Legendary British boxing trainer, Brendan Ingle once talked of boxing as a “dirty, rotten prostituting game,” as well as “the most beautiful thing that you’ll ever see”.

And this is where you come in, continue on and finish when reading the biography of former boxer and now trainer Glyn Rhodes MBE, a one-time boxer from the Ingle stable. Throughout the book, it is tragedy which haunts it, whether hinted at or explored and explained in some depth. It reminded me of a pub trivia question to which the answer is Kenny Dalgliesh. The question is: name the international footballer who was a fan, player and manager at each of the following tragedies – Ibrox, Heysel and Hillsborough. Boxing has similar tragedies that are as prescient in the minds of British boxing fans as the three hitherto named tragedies are in the minds of hard-core football fans: Michael Watson, Bradley Stone and Scott Westgarth. Former professional boxer and trainer, Glyn Rhodes MBE was in the audience for Watson, the trainer of the opposing fighter for Stone and Westgarth’s trainer. Rhodes is clearly battle hardened and through his book, you get beyond the old cliché of a man born into unfortunate circumstances who found salvation in a gym.

It is notable, and to the book’s credit, that Rhodes is helped by an author who is no stranger to the dark side of the sport, collaborator Mark Turley. Turley’s book, Journeymen sent some into a tailspin after they felt he told too many honest tales from fighters most think are paid to lose.

Rhodes begins with the typical childhood route to the gym: restless child, unable to settle in education and trouble in the streets. Then one day he finds a gym. And with such a cliché intact he comes across that legendary figure in boxing: Brendan Ingle. Ingle carries a lot of kudos and cache in the sport. An Irishman who settled in Sheffield, England, Brendan Ingle established a gym, the Wincobank, that developed some of the most famous names and several world champions. However, for all the ones who lionize him, there seem to be a few who have a different, perhaps more balanced view of him and therefore of his influence on their careers. One of those is Glyn Rhodes, or as Brendan used to call him, Glen.

Rhodes himself is now an MBE for services to boxing, having established his own gym and been his own form of salvation within his own community. Rhodes has worked with some of the best British fighters over the last twenty or thirty years, and this book tells that tale which exposes his and the sport’s underbelly: of a machismo driven by dedication, which is deemed essential in boxing, to confront things which are beyond both good and evil – hence the title.

And so, Rhodes’ story is intertwined with the enigmatic Brendan who took the boys on long walks to pontificate and in the beginning, foreshadows the despair felt when things went wrong. Credit is given to Brendan when Rhodes got the chance to travel further afield, to tournaments with fantastic opportunities and new experiences. Rhodes found a life outside the Steel City of Sheffield, his home, but we can feel the beginnings of fracture, which is common in the boxing world between manager and boxer. In the recent past we have seen a BBC documentary series charting the close bond between two weight world champion Carl Frampton and Barry McGuigan’s family, which was followed a few years later with BBC cameras filming each of them entering the court room to settle their battle.

But the problem with Rhodes, the boxer, was that he was struggling to find the dedication needed to be a contender, was better suited to being an entertainer, and owned his nickname, “Showboat” with aplomb. He clearly realized that his living was not going to be made headlining shows in Las Vegas car parks, but in small hall fighting towns where the respect given to anyone stepping into a ring was touchable. He was described after his 1981 fight against Brian Snagg in the Liverpool Echo, as “a punter’s dream… a manager’s nightmare.” Boxing News, the respected British trade paper even called him, “the clown prince of boxing.”

Small hall boxing depends upon fighters selling tickets. The economics are very simple. If you want to fight, sell the tickets and then you can get paid. From that pittance will come paying your corner team including your trainer. Sell loads of tickets, happy people all round. Sell too few and then that is a huge problem. Rhodes, though a great entertainer, didn’t sell enough tickets to make himself important, didn’t train as dedicatedly as anyone else and wanted only smiles all round to keep his place in the ring secure. Ingle did indeed have a nightmare on his hands. Rhodes was increasingly becoming a cliché. His career was stuck in the cul de sac of what legendary boxing promoter, Mickey Duff called, the “who needs him club.” The truth was nobody needed him. Rhodes pulls no punches about this and hides nowhere in his prose, thanks to Turley. The management of his career was faltering and led to an increasingly fractured relationship with Ingle. Ingle would often call up Rhodes with his legendary Irish drawl to announce, “Glen I’ve got yous a fight.” Rhodes became suspicious when he fought for a regional title, the Central Area title, and lost to Willy Wilson. Having been postponed, Rhodes went on holiday, returned and Ingle told him it was back on – in a fortnight. Rhodes had not been in training, making his preparation short and ill advised. Rhodes believes he was set up, and Ingle knew all along what was happening. Rhodes was becoming a pawn in Ingle’s game.

If his prose measured in describing his own boxing ability, it matches the descriptions of exceptional boxers who trained alongside him. Although Herol Graham remains for most of us, the best British boxer never to win a world title, he was certainly one of the most influential, as described by Rhodes, in the gym and amongst other boxers. That his current mental ill health dogs him as described alter in the book is a reminder of the perils of the sport. Graham was a sublime boxer. “He was everything I was not,” admits Rhodes. When Graham fell out with Ingle he managed to convince Rhodes, after a period out the ring, that he should return to it. He did, but boxing’s black arts once more saw that Rhodes did not get “the decisions I deserved.” It was bittersweet and he felt it – Rhodes was picking up some sponsorship, critical for boxers to be full time, but he was still losing. Then Brendan pulled him back in and Rhodes was exposed again to the seedy side. In a fight against George Bagrie, it involved Rhodes being told that he was only going into the ring to give Bagrie some practice but found that the message had not gone across from his red corner to his opponent’s blue one. It was a fight he had been convinced to take by Ingle. Instead of an easy night, his opponent went in to knock his head off. There were plenty of other times when his sixth boxing sense said don’t do it, but the Irish blarney convinced him he should.

Not all boxers get such praise and amongst the animosity of his gym and Ingle’s gym there are harsh words reserved for fellow professionals – Johnny Nelson and Dave Caldwell in particular. On one occasion Caldwell, according to Rhodes, sent his fighter to the slaughter, not once but twice – all in aid of a TV deal. Rhodes’ contempt is fueled by his commitment as trainers have a duty of care towards their fighters and the most intense moments come when Rhodes recounts the tragedies that follow from a sport with two people in a small ring, trying to beat each other to a pulp by hitting each other in the head.

His first encounter with tragedy was the night that Chris Eubank Sr. beat Michael Watson and Watson almost died. It is a sober read to hear of how Rhodes went from the changing room as a fighter, after being beaten by Eamon Loughran to watching something unfold which “drained some of my remaining motivation.” After his fight with Eubank Sr., Watson collapsed and, as there was inadequate medical provision at the ringside, almost died, but ended up with life changing brain damage. He sued the British Boxing Board of Control and won millions in a lawsuit which has made his life as comfortable as it can be. He still attends boxing matches, speaks eloquently when asked to do interviews, and once managed the London Marathon, being helped over the line by the other man in the ring, Chris Eubank Sr. But at the time of this unfolding tragedy, there was more than a collective holding of breath. Unsurprisingly it led to massive changes in the sport. Rhodes is vivid in his view as he was close enough to feel the tension and horror of the event.

Rhodes’ second brush with tragedy came when he trained Ricky Wenton. The tragedy of Bradley Stone is known throughout the British boxing world, because and despite of all of the changes made, his life was to be cut short after fighting Wenton. Having watched from ringside as Michael Watson almost died, Rhodes was now a trainer watching it from an opposite corner; it had moved closer to him. As Rhodes struggled, the loneliness gripped him as he reveals, “I wanted to call someone, but who could I call and what would I say?” Little did he know that he was still far from finished with death from the ring.

Meantime he was still creating a worthy gym and having to deal with the antics of his rivals in the city. Ingle’s cohorts had taken to stunts to rile Rhodes. This included when Prince Naseem Hamed fought one of Rhodes’ stable of fighters, Billy Hardy. Hamed and his team all turned up in comical outsized ears to the press conference. To be fair, Hardy had a fair spread of ears on him, and Rhodes was able to see the humor in it all. It was relief in a darkened world. As the final chapters of the book unfold, we get the most affecting tragedy of all: Scott Westgarth.

Having won his English title eliminator, Westgarth, came out the ring, sat on its apron and spoke eloquently to an interviewer live on television. He walked to the dressing room, collapsed, went to the hospital with Rhodes, had a fit in the back of the ambulance and eventually died in hospital the following day. Rhodes, after all the tragedy he had seen was broken again. It is a tough read, especially after Rhodes has recounted another one of his fighters, Sam “Speedy” Sheedy having been diagnosed with a bleed on the brain. It came after Sheedy had simply given up in a fight and was stopped. Quick work got Sheedy the help he needed; no work was going to save Westgarth.

In amongst the narrative there are further tales told of Herol Graham’s last hurrah in America, and of a royal visit to Rhodes’ gym when a refuge he forgot to tell Special Branch about was found in a cupboard.

As for the feud with Brendan Ingle, it ended. Rhodes was asked to the Ingle gym to sort it out with Brendan. Thanks to Dominic, Brendan’s son, himself now a well-regarded trainer, the visit became the closure Rhodes needed. It happened before the end for Brendan and his passing. And then, afterwards Rhodes was asked not to go to the funeral. His reflections are mixed, rightly so, but demonstrate quite a subtle comprehension of what happened. It marks Rhodes out as a man who has considered and understood much about the brutality of his relationship with the sport of boxing. And so, knowing more about how it affected him would support many in his field and open up the idea that masculinity can be multifaceted.

Despite all the tragedies and the fact that the vast majority of boxers do not make enough money to live comfortably, Rhodes continues. He became a trainer and continued his enmity with Brendan Ingle. Setting up a rival gym in the same city may not have endeared him to his former mentor but it also led to uncomfortable nights at events – when Ingle checked his ringside tickets at the Prince Naseem Hamed Vincenzo Belcastro fight, confrontations in his own gym – when Brendan visited only to berate Rhodes, and a challenge at a British Boxing Board of Control hearing to have him removed – refused but ended with Rhodes being fined.

As well as the revelation that Herol Graham, someone he looked up to in the gym, who was a poster boy for the sport in his heyday and was a much admired and beautiful exponent of the sweet science is now in an institution getting the help he needs, it is a tough ending. It is a paradox that you will still find Glyn Rhodes MBE is a man who is still training future fighters. There is a lot of material in here which literally pulls few punches, admits his part in some of the seedier side, but also delivers some very contentious opinions of how he and others needed this discipline to escape the poverty of his life – literal and metaphorical. As to what it adds to our understanding of what it means to be a man in a masculine world, that is still not quite as erudite as you would hope, but there is still some hope that it shall follow.

And so, if you are looking for a sporting life, in a contentious sport, then you have plenty to savor. But Rhodes the man, like many boxers are closed books. Their emotions are aggressively public but in their quiet moments their lives can oftentimes fall apart. Here, rather than getting an expose you get a glimpse. Current toxic masculinity could do with Turley, as the collaborator, working Rhodes a little harder. There are events which reach into the emotional void as 15 years of togetherness with his partner comes to an end, just as he goes out to train Clinton McKenzie for his fight against Tavoris Cloud. We could do with how his obsession with his sport, his solace, his escape and his salvation led to that.

To buy the book in America.

To buy the book in the UK.