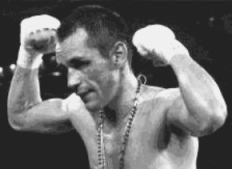

Ricardo Lopez: Greatness in a Small Package

—————————————————————————————————————————-

By Mike “Rubber Warrior” Plunkett

By Mike “Rubber Warrior” Plunkett

For years it has been said that North American boxing fans tend to only focus, for the most part, on the higher weight classes. Fighters from welterweight on up to heavyweight were what people wanted to see. In that regard, I was no different. My original focus of course was Muhammad Ali and the heavyweight division. As time went on, I began to keep tabs on pretty much every division from lightweight on up, save for the occasional bright light such as junior featherweight great Wilfredo Gomez or featherweight great Salvador Sanchez. Even then, the opportunity to watch a lower weight class fighter or world champion wasn’t always so readily available. The big networks and cable outlets were more concerned about catering to the masses, and at the time, English-speaking fighters weighing in excess of the average guy on the street was the preferred serving on the menu.

During the period when Mike Tyson was originally incarcerated and Don King was busy putting together those fantastic multi-layered championship fight cards, Ricardo Lopez, a very diminutive ring artist was busy defending his WBC Minimumweight, or to some, Strawweight Title on the under cards and quietly amassing an extraordinary championship record.

Over a significant period of time, Lopez was undeniably brilliant. He didn’t display extraordinary athletic prowess or have a flashy style. His orthodox stance didn’t suggest anything complicated and while heavy-handed, he wasn’t a true one-punch knockout artist. He won through studied technique, mental strength and a well of self-belief. There were very few explosions and mushroom clouds. It was all about studied craft, laser-like precision, impeccable timing and a rare focus despite performing in relative anonymity.

I was introduced to Lopez by my good fight buddy Jeremy, a second to none collector of bouts from all around the globe. As was his habit back in the day, Jeremy would occasionally put together for me, VHS tapes of all of the relevant bouts of that period. The Don King fight cards almost always would be recorded for my consumption, in full. As always, tucked away neatly between title bouts featuring known marquee names such as Terry Norris, Felix Trinidad or Julio Cesar Chavez, I’d find a match featuring Ricardo Lopez in defense of his WBC Minimumweight Title.

My first recollection of seeing “Finito” in action was in a seemingly effortless shutout of the then undefeated Kermin Guardia on the under card of Julio Cesar Chavez’ inglorious rematch with Frankie Randall. It’s a strange base point of recollection, I suppose. The card was set-up as “JC Superstar’s” return to glory off of his first official defeat earlier that year at the hands of Randall. Yet for anybody watching that night, the best Mexican fighter on the card weighed no more than one-hundred and five pounds. I’m certain that those with a sharp eye for talent had to take note of the poise, style and near effortless application in which “Finito” Lopez defended his title.

As time went on, I requested more on Lopez, including his first title win from 1990 against defending champion Hideyuki Ohashi. Another bout that made me realize I was onto something special was his notable title defense against Saman Sorjaturong, a fighter that he would dispatch with apparent ease in the second round. Down the road, that win would take on a whole new level of meaning when Sorjaturong would go on to prove his own level of worth by defeating the great Humberto Gonzalez for the WBC and IBF Light Flyweight Titles in 1995, ultimately defending that title almost a dozen times through 2001.

How special was Ricardo Lopez? He was never in any real danger of losing a fight until his technical draw with Rosendo Alvarez, the WBA Minimumweight Champion in a 1998 unification match. It was Lopez’ forty-eighth fight and it took that long to find a guy that could really challenge him. Eight months later, and after much speculation that he may be in decline, Lopez managed to best Alvarez by split decision in a tightly-contested rematch. With “Finito”, it wasn’t just about getting paid or staying undefeated. It was about honor and pride. There had to be no question as to who was better or who was champion. In all, he defended the Minimumweight Title a record twenty-three times.

In 1999, Lopez moved-up to win the IBF Light Flyweight Title against Will Grigsby, ultimately making two title defenses and holding that crown for some two years before hanging-up the gloves. Too bad he was under contract to Don King and buried among prelims or all but forgotten when clamor was being generated for the Christy Martin’s and Isra Girgrah’s of the sport.

One other point to consider was the division Ricardo Lopez won his first championship in. To some purists, minimumweight/strawweight wasn’t a legitimate division. In truth, it was created in 1987 in order to accommodate the most diminutive of fighters, providing a level playing field for those too small to properly compete at one-hundred and eight pounds in the next division, light flyweight, a division three pounds northward. Had Lopez been born some sixty years before, he’d have been forced to compete as a flyweight, facing men at one-hundred and twelve pounds as opposed to having the luxury of competing in a division that accommodated his natural weight. In any event, it’s this writer’s opinion that boxing has in some ways evolved for the better, and having a division in place for the smallest of men seems to make complete sense.

Would Lopez have been as successful had he been forced to compete among bigger men from day one? As stated earlier, he did eventually win a title at junior flyweight, but it came towards the end of his career when he was well into his thirties, physically filling-out and arguably better suited to hold the additional weight. I suppose for some, the very fact that he flourished in a recently created weight class suited perfectly to his dimensions detracts from his accomplishments, but even so, one has to acknowledge that it isn’t every day a champion is able to defend his title twenty-three times, then going-on to win a second championship, years beyond his prime form. In the lower weight classes, 30 years of age mostly spells doom. Only the most well preserved and special can prevail.

With a career record of 51-0-1 with 38 KO’s, eleven years at the top, championships in two weight classes and a total of 25 title defenses to his credit, there can be little doubt that Ricardo Lopez was truly a great fighter and an almost sure fire bet to be inducted into the International Boxing Hall of Fame on his first ballot.

In the period between 1992 and 1994 when the boxing media was brandishing the Don King-induced notion that the great Julio Cesar Chavez was Mexico’s greatest warrior, I had little doubt that in actuality, Mexico’s best fighter of that period, and one of it’s very best fighters of all time was in actuality Ricardo “Finito” Lopez, mainstream notoriety and popularity be damned.