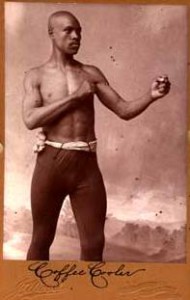

Frank Craig “The Harlem Coffee Cooler”: Do You Take Your Boxing Legends With One Lump or Two?

By Chris “Man of Few Words” Benedict

By Chris “Man of Few Words” Benedict

“Mr. Archibald of the Standard Oil got tickets for us…went to the Athletic Club last Saturday night and saw the Coffee Cooler dust off another prizefighter in great style,” Mark Twain wrote to his wife Olivia on January 4, 1894 after watching Frank Craig defeat Joe Ellingsworth in New York City.

“There were 10 rounds, but at the end of the fifth the Coffee Cooler knocked the white man down and he couldn’t get up anymore (official records list it as a 7th round KO). A round consists of only 3 minutes, then the men retire to their corners and sit down and lean their heads back against a post and gasp and pant like fishes while one man fans them with a fan, another with a table-cloth, another rubs their legs and sponges off their face and shoulders and blows sprays of water in their faces from his own mouth. Only one minute is allowed for this, then time is called and they jump up and go to fighting again. It is absorbingly interesting.”

The man Mark Twain was so taken with was Frank Craig, who at that time was the Colored Middleweight Champion and kept company with “Barbados Demon” Joe Walcott (no, “Jersey Joe” was not the first) and George Dixon, the first black world champion in any division (first in 1890 as bantamweight and a year later at featherweight), nearly two decades prior to Jack Johnson and even twelve years before the great lightweight Joe Gans dethroned Frank Erne courtesy of a first round knockout. By virtue of the fact that Dixon was born in Nova Scotia, Canada, Gans is credited with being the first African American (emphasis on American) champion.

Furthermore, Frank Craig, as mentioned by the former Samuel Clemens, also had what simply must be the best and most original nickname in the colorful history of the fight game.

“The Harlem Coffee Cooler”. How no outside-the-box-thinking café owner in Harlem ever appropriated his name to feature on a sign above the door of their beanery is beyond me. In any event, given to the hyperbolic predilection of accepting and co-opting tall tales as gospel truth as Ring Magazine founder Nat Fleischer may have been, he swore by the account given by George Dixon as to how Craig’s moniker was bestowed upon him in the fourth of five volumes of his masterful study of African American pugilists Black Dynamite.

Haunted by the ceaseless challenges of a local “gutter fighter” known as “Bully” Singleton, who harbored no aspirations toward a legitimate boxing career and was envious of the attention being given to Craig because of his, Frank quite literally took matters into his own hands one night in a restaurant where he and a friend were dining. Nursing a nasty hang over which hardly helped his already characteristically surly mood, Singleton stumbled in and ordered “black coffee, hot, and plenty of it.” Taking notice of Craig, he immediately began hectoring the prizefighter, trying to tempt him out into the alley. To his surprise, Craig had had enough of Singleton’s shenanigans and called his bluff before “Bully” could take a sip of his first steaming cup, which Singleton assured the excited patrons “will be plenty hot when I come back here.”

He may have been born on April 1st (in 1868), but Craig was no one’s fool. Without landing a single punch, as the story goes, Singleton was greeted with a straight left from Frank, followed by right hooks to the jaw and body shots with both hands before being laid out with a lip-splitting right uppercut. His antagonist showing no signs of life, Craig joked that “I guess his coffee will be cool enough by the time he gets round to drinking it.”

“The Coffee Cooler” put an exclamation point on his April 7, 1891 fistic debut with a 10th round knockout of Seaman Fisher, who would have been better suited to a career in marine biology from the sound of his name and, considering that this seems to have been his only fight, may well have been persuaded to switch vocations. His first loss came against Billy Dunn by way of 3rd round knockout in his fifth professional scrap and would manage no better than a draw in their two subsequent instances of renewing hostilities. Sandwiched between the Dunn fights was an opportunity for “The Coffee Cooler” to put his appropriately named opponent GW Coffey on ice in the first round.

Frank challenged Philadelphia’s Joe Butler for the Colored Middleweight Title on March 18, 1893 and was rewarded for his efforts in traveling to Butler’s hometown by falling victim to a 2nd round knockout. Having rebounded with victories over Steve O’ Donnell, an Australian heavyweight and protégé of Peter Jackson, and O’ Donnell’s countryman Billy McCarthy, avenging a prior loss to the highly regarded Aussie middleweight, Craig next took on Joe Ellingsworth in the aforementioned match attended by the author of the adventures of Tom Sawyer and Huckleberry Finn. It was arranged by New York Athletic Club matchmaker Mike Donovan who offered Ellingsworth a $200 incentive on top of the $1,500 purse if he could knock “The Coffee Cooler” out. Instead, Joe peeled himself off the canvas and walked off empty-handed.

Consecutive four-round points losses to undefeated Australian middleweight champion Dan Creedon were equalized by a battering of Dick Baker at New York’s Lenox Lyceum so one-sided, reported The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, that police stormed the ring to stop the fight after Craig had knocked Baker down for the third time in less than a minute. The four-round decision rendered in the rematch with Joe Butler went Frank’s way and, in unfriendly Philadelphia no less, “The Coffee Cooler” was crowned Colored Middleweight Champion on February 20, 1894.

With George Dixon in his corner, Craig faced off against Peter Maher, an Irishman renowned for a murderous right hand, at the Boston Music Hall five months later. Respectfully wary of Maher’s right, Frank fought defensively, jabbing and counterpunching from a safe distance, but buckled Maher’s knees with a right cross of his own before the bell ending the second round, as Fleischer misremembers-the fight actually ended in that stanza. John L. Sullivan, sitting ringside, leapt upon the ring apron and, shoving Maher’s seconds aside, ministered to the shaken Irishman with a whiskey bottle. “Take a swig of that, Peter,” urged Sullivan, “then go in and knock his head off.” Which is damn near what happened as a rejuvenated Maher smashed a punishing right uppercut into Craig’s jaw. “Frank’s feet shot into the air, he seemed to turn a half hand-spring, and crashed sideways to the floor,” Fleischer wrote. George Dixon, not alone in fearing that his friend might be dead, dashed between the ropes to watch in relief as Craig was revived by a bottle of ammonia held beneath his nostrils. This would be his last fight on American soil for more than five years, as he would vacate the United States, not to mention the Colored Middleweight Title he never once defended.

Frank Craig followed in the footsteps of “The Black Prince” Peter Jackson who, just years before, had crossed the Atlantic and enjoyed not only professional success but celebrity status. Similarly, the British citizens seemed as smitten with “The Coffee Cooler” for his proficiency at prizefighting as they were his penchant for chewing gum, a trend that accelerated considerably in the wake of Craig’s arrival in the United Kingdom. His London debut saw him square off against John O’ Brien at Covent Gardens’ National Sporting Club. “The Coffee Cooler” apparently had a taste for pastry and was seen dictating a telegram to an usher from his corner inside the ring intended for his landlady who had promised him apple dumplings upon his return home. Sensing a short night’s work, Craig asked that she have them ready sooner than later. Sure enough, it took all of two rounds for Frank to dispose of O’ Brien and he was forced to waste little precious time in satisfying his sweet tooth.

His British sojourn began with a winning streak of a baker’s dozen. Craig fought 11 times alone in November 1894 (five days in a row at one stretch), all but one of those victories coming by way of knockout. A faceoff with Frank Slavin at Holborn’s Central Hall did not go nearly as well. Having publicly mocked the tentative Australian until he finally relented to Craig’s taunts, Frank “entered the ring attired in a huge green dressing gown” and “sat in the corner playing a mouth organ whilst awaiting the arrival of Frank Slavin”, according to the Cessnock Eagle. Scheduled for 20 rounds, Craig came out of a crouch in the opening minute of the fight only to be instantly obliterated by a left/right combination.

What was supposed to have been an April 13th meeting with Ted Pritchard wound up being a re-acquaintance with John O’Brien instead. The Yorkshire Herald published an account of the evening which claimed that O’Brien was a last-minute replacement for Pritchard who was suffering an undisclosed illness. Evidently O’Brien had been “drinking in a pub from which he had to be fetched, entered the ring blind drunk, and had a job standing up before somehow getting through the first round, only to retire.”

It was right around this time that Craig was swept up into the web of intrigue enveloping Oscar Wilde’s 1895 indecency trial when a 28 year-old laborer named Vincent Crawford (or vice versa) survived a suicide attempt after jumping out of his window rather than be subject to the threats alluded to in a series of letters from Wilde. Whether Crawford (or Vincent) was involved intimately or simply peripherally with the Pictures of Dorian Gray author, it is safe to assume that he must have been in possession of some rather scandalous knowledge concerning Wilde’s homosexual lifestyle which was the focus of the smear campaign. It is suggested that the missives contained warnings that Vincent’s testimony would lead to grievous bodily harm and rumors swirled that none other than “The Coffee Cooler” was the ruffian intended to carry out Wilde’s supposedly sinister bidding.

Frank Craig returned to his native New York in September 1899 to much pomp and circumstance. His steamer was met at the harbor by thousands of spectators, so many so that-while a brass band played “Hail to the Chief” (verses having been adapted from Sir Walter Scott’s The Lady of the Lake, appropriately enough)-two people were nudged off the dock and into the waters below from where they required rescue. Unfortunately, the pugilistic displays put on by “The Coffee Cooler” after the fact did not exactly justify such ceremony, winless in four fights. Two of these losses came against Jack Root who, six years later, would go up against (and get knocked out by) Marvin Hart for the World Heavyweight Title vacated by James J. Jeffries who also refereed the contest.

Craig’s return to London would go uninterrupted but for a handful of trips to Ireland from that point forward. In August 1900, “The Coffee Cooler” put on a sparring exhibition at Sunderland that concluded with his customary challenge to anyone present to last three rounds with him, one which was taken up by a dock worker who Craig demolished with no apparent problem. The crowd took exception to the treatment of the local strong man and it is said that an orange thrown with great velocity from the music hall’s upper rafters was sufficient to floor “The Cooler”. Be that as it may, irate shipyard workers set upon the stage to exact revenge in the name of their fallen comrade and Craig was only able to flee to the safety of his dressing room seconds before the heavy protective curtain descended from the ceiling. In what came to be known as The Sunderland Riot, the bloodthirsty mob raged through the streets outside, taking out their frustrations by horribly beating a black acrobat who had been performing on the bill as well because he resembled “The Coffee Cooler” closely enough to suit their awful needs.

Craig is supposed to have worked in conjunction with promoter Bella Borge to stage a battle royal at Blackfriar Ring in London’s East End. These sad spectacles involved up to a dozen black men (sometimes blindfolded) fighting for the amusement and profit of mostly white bystanders and, for the victor, perhaps a bottle of rot-gut whiskey or whatever pocket change was tossed onto the canvas. This unsubstantiated incident is supposed to have worked out in the financial favor of “The Coffee Cooler” when he inserted a pre-arranged ringer into the competition who easily emerged as the last man standing, earning a handsome sum from local bookmakers which was split between the mischievous co-conspirators.

Though gaining in age and slipping in strength and dexterity, Craig fought on until 1912 and even staged a one-night-only comeback ten years later, a three-round decision loss to Jim Rideout. Frank’s official career record stood at 69-39-10, 43 KOs. The October 16, 1937 issue of Britain’s News of the World carried a story chronicling the sad decline of “The Coffee Cooler”, appearing before a magistrate after having been charged with striking a black woman over the head with a bottle. Furthermore, the article stated that Craig, now in his late sixties, had been reduced to $25 a week stints in boxing booths at fairs and carnivals, taking on any and all comers.

Frank Craig died in Chelsea, England in January 1943 at the age of 74. In his travel book Following the Equator, Craig’s one-time admirer Mark Twain wrote that “Truth is stranger than fiction, but it is because Fiction is obliged to stick to possibilities. Truth isn’t.” However vaguely Craig’s legacy may be mired between the distant realms of reality and speculative fantasy, one thing remains certain.

“The Harlem Coffee Cooler” is the uncrowned champion of badass boxing nicknames.

[si-contact-form form=’2′]