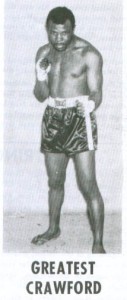

Greatest Crawford Died Trying To Live Up To His Name

“How can Cassius Clay say he’s the Greatest?” asked an incredulous Crawford. “I’m the Greatest. That’s my name.”

“The Greatest” may have been Muhammad Ali’s self-applied, dog-eared, bent-and-torn calling card, brandished at every opportunity, as well as the title of his autobiography, but Greatest was the legal name typed onto the birth certificate of Johnny and Mattie Crawford’s baby boy filed at Hurtsboro, Alabama’s City Hall in 1937. “He was such a beautiful, fat baby who weighed 11 pounds,” Mattie later reminisced, “and to me he just looked like the greatest. I decided to name him that.”

Hyperbole can be one of the best friends to a boxer who puts self-promotion on par with pugilistic skills. The fighter that devotes as much time and effort into crafting artful insults and narcissistic bloviation as they do perfecting sound defense, stiff jabs, and a hook thrown from the depths of hell walks a fine line. Some bulldoze right over it. When Floyd Mayweather Jr. elevated himself to “Greatest” or “The Best Ever” status over Ali, Henry Armstrong, and Sugar Ray Robinson during the pre-fight hype to the Sleight of the Century against Manny Pacquiao, Mike Tyson verbally slapped the Money-lover with the characterization of “a small, scared, delusional man.”

Greatest Crawford, who earned more recognition and possibly financial compensation as a sparring partner than as a light-heavyweight contender, couldn’t be bothered walking the walk or talking the talk of his more egocentric peers. A November 28, 1966 Sports Illustrated article described Crawford as “an aloof, slightly reserved person whose sense of dignity was as conspicuous as his thick mustache.” Despite his name, perhaps in spite of being known as Greatest, Crawford even seemed disinterested in dressing the part. The Sports Illustrated piece proceeds to paint a fairly vivid portrait of Greatest by referring to him as “a singular man whose unique attire—a beret, a business-suit jacket, unmatching pants, a tab-collar shirt buttoned at the throat but no tie, heavy work boots—made him stand out even in a training camp.”

Having moved with his parents and nine siblings to Brooklyn as a young man, Greatest Crawford began boxing as an amateur at 17 and made his professional debut at the age of 21 as a middleweight with a four-round points win over Leroy Holmes (who would win only three of his 16 career fights) at the Eastern Parkway Arena on March 15, 1958. He would fight seven more times that year, winning each with the exception of a six-round draw against former New York Golden Gloves winner Rudy Corney in the second of their two meetings at the St. Nicholas Arena. A little less than two months later, Crawford made his Madison Square Garden debut with a decision victory over Philadelphia’s Eddie Wright on the same card that saw legendary welterweight Gaspar “Indio” Ortega fight to a draw with Rudell Stitch when Stitch refused to take advantage of a clearly groggy Ortega following an accidental third-round head-butt. Not unlike Crawford but for the circumstances, Stitch would tragically perish as a young man. Rudell was only 27 when he was pulled into the Ohio River during a sadly futile attempt to save the life of his friend Charles Oliver, who had slipped in off of a ledge. Both men were swept under the rip current and drowned. Although he (again, like Crawford) never did wear a title belt, Stitch was posthumously decorated with the Carnegie Hero Medal for his selfless sacrifice.

Greatest first tasted defeat at Madison Square Garden on November 12, 1960 at the hands of Ike White which was one of only 19 wins in 63 career bouts for White, 9 of his 40 losses coming to future greats Holly Mims (four times) Jose Torres, Joey Giambra, Luis Gutierrez (twice), and Bennie Briscoe. Rebounding with consecutive wins at St. Nicholas Arena over Mel Fulgham and Sam Jordan (in Greatest’s debut at light-heavyweight), Crawford spent the late spring of 1961 not only preparing for his own June 10th fight at the Garden against Tommy Hough but sparring with that night’s main-eventer Archie Moore who would go in for the second time against Giulio Rinaldi, this time in defense of his NYSAC light-heavyweight title, having been stripped by the NBA of their portion.

A.J. Liebling, who was covering the duration of Moore’s training camp-up to and including the fight-for an essay called Ad Lib which would go unpublished until the release of the book A Neutral Corner more than 30 years after his death, spoke of Crawford as “a cool, fast boxer who, it was evident, studies the Master as they go along-a learn and earn course.” Because “The Old Mongoose” had been smothered, frustrated, and ultimately defeated by Rinaldi’s pressure-cooker style in their first fight in Italy eight months prior, Archie employed Greatest as a suitable surrogate. “He kept moving into Moore, doubtless by instruction,” Liebling reported, “and Moore, in a guard peculiar to him-elbows high, forearms horizontally across his body-moved, swaying, just inside the elbows, until he saw a chance to counter. They rehearsed again and again the development of a certain situation-a crowder swarming all over a hitter, who tries to spot an opening. Crawford did not rehearse leaving an opening. He did his best to avoid it, and since he is extremely fast, the patriarch had excellent practice.”

Practice evidently made perfect for both master and apprentice. Archie Moore beat Rinaldi to a bloody pulp en route to a 15-round unanimous decision and Greatest Crawford earned a TKO victory by virtue of a stoppage due to cuts on Tommy Hough’s head in the fourth. Greatest, wrote Liebling, “kept stepping within the arc of the scythes and punching the club fighter’s face as if it were a light bag. He is a solemn-looking boy and as he worked away on Hough he occasionally looked bored, like a young man told to beat a carpet when he would rather be out playing baseball.” Hough protested what he believed to be the referee’s premature intervention, prompting Liebling to remark that, “If Greatest, ad-libbing, had stepped aside just once during the bout, Hough might have fallen on his face and knocked himself out.”

With his record standing at a respectable 12-1-2, Crawford ventured outside New York City limits for the first time as a prizefighter, twice defeating Sid Carter in the state of Washington, but dropping a decision to Carter-and one to Archie Ray for good measure-in between.

Attempting in vain to disregard the expiration date stamped on his status as a legitimate light-heavyweight contender, Greatest returned after more than two years to his more hospitable stomping grounds, posting back-to-back wins (for the last time in his career) over Jimmy McCarter and Henry Palmer at Madison Square Garden. A one-year layoff would follow the first fight of his trilogy with Levan Roundtree at Queens, New York’s Sunnyside Gardens on December 8, 1964. He spent this time as a hired hand for George Chuvalo, the Canadian heavyweight with the pompadour and granite chin. Having previously assisted George in preparing for Doug Jones, he was welcomed back into the fold as a stand-in for Floyd Patterson, Chuvalo’s 1965 Fight of the Year adversary. Because he had sparred with Patterson, and possessed a similar physique and style, Crawford made for a logical stunt double. As Chuvalo would soon learn, these attributes also made him a dangerous ally. A switchboard operator at Kushner’s Resort revealed that Crawford had been conversing with Dan Florio, a strong link holding together Floyd Patterson’s inner circle, allegedly warning Patterson away from in-fighting as “George is way too strong for Floyd” and further suggesting that Patterson “run like hell”.

“Although Crawford’s treachery surprised and disappointed me, we did nothing about it because I liked Greatest and felt no animosity toward him,” George Chuvalo wrote in his terrific memoir, A Fighter’s Life. “Either way, he disappeared from camp the day after we found out, and Teddy (Brenner, the Garden matchmaker) was convinced he’d been whisked straight to Patterson’s headquarters in Marlboro, New York, about 50 miles away.” Chuvalo’s recollections of Greatest were of him being “scrawny, with long arms and a wispy goatee. He was a man of few words,” George continued, “but when he said something in that deep, resonant voice of his, it was usually pretty good. Crawford was a pretty decent fighter too, although he would have been a hell of a lot better if he hadn’t smoked so much. His breath always smelled heavily of tobacco, and every time I whacked him to the body it was just like somebody blowing smoke in my face.”

The aforementioned Sports Illustrated article mentions that Greatest subsequently walked away from another (unnamed) high profile fighter’s camp after being expected to share “a room the size of a closet” with two other sparring partners, stating defiantly that “a professional fighter has pride.” Crawford would shortly afterward pull off a split decision upset in the main event at Portland, Maine’s Exposition Building over 20-5-4 Milo Calhoun, a rugged Jamaican who had gone the distance with Nino Benvenuti, who was 55-0 at the time, hanging tough in a points loss one year earlier and would repeat the same feat 10 months after facing Greatest, as well as defeating Philadelphia phenom George Benton. By then, Crawford would be dead.

Twenty-nine year old Greatest Crawford was matched against heavy-hitting hometown favorite Marion “Thunderbolt” Conner (22-6-1) at the Memorial Auditorium in Canton, Ohio on November 16, 1966. Knocked out in the 9th round, Crawford never regained consciousness and was rushed into emergency surgery to remove a blood clot on his brain. He died two days later of “severe brain damage with contusions and hemorrhaging” according to Stark County coroner G. S. Shaheen.

“I hated boxing, and I never wanted my son to be a fighter,” expressed Greatest’s mother Mattie, who nevertheless confessed that “it was his big love. He just lived to fight and was at the gym every day to train.” Mrs. Crawford couldn’t help but circle back around and reiterate that “I hated the cruelty of boxing.” In a manner reminiscent of Davey Moore’s widow Geraldine consoling Ultiminio “Sugar” Ramos “whose fists laid him low in a cloud of mist” as Bob Dylan memorialized in song, Mattie Crawford spoke similar words of cold comfort to Marion Conner: “It’s one of those things that happens. I know you didn’t want it this way.”

“What’s in a name?” Juliet inquires of her star-crossed lover Romeo in Shakespeare’s romantic tragedy. Greatest Crawford answered the timeless question this way. “If I had spent the last eight years in a factory or shining shoes, then I’d probably have some money and a pretty good job. But I’d be a nobody. This way a few people know my name. I’m somebody. To me, that’s important.”

[si-contact-form form=’2′]