Who Killed Davey Moore? The Resurrection of “Sugar” Ramos

[AdSense-A]

Bob Dylan, a fight fan who once went round for round with Ray Mancini (himself haunted by the ghost of Duk Koo Kim) in the ring which dominates the gym of his Santa Monica home, implored “Boom Boom” to lay off the head shots because “I have a few songs left in there.” The brain cells remaining in Dylan’s cerebellum were responsible for scores of folk ballads, protest anthems, timeless pop tunes, and a few boxing songs too.

He had devoted the entire second verse of “I Shall Be Free No. 10” off “Another Side of Bob Dylan” to Cassius Clay, covered Simon and Garfunkel’s “The Boxer” on his “Self- Portrait” album, wrote and recorded “Hurricane” for 1975s “Desire” to draw attention to the plight of falsely imprisoned middleweight contender Rubin Carter, donating proceeds from his Rolling Thunder Revue Tour to aid Carter’s legal defense fund.

“Who Killed Davey Moore?” served as a multi-tiered indictment of those responsible for the boxer’s demise, each verse attempting in vain to assign blame for the 1963 ring death of Moore, at the hands of Ultiminio “Sugar” Ramos, to a succession of worthy suspects (the referee, the angry crowd, the cigar-chomping manager, the gamblers, the writers, and Ramos himself), only for one after the other to exonerate themselves, scrubbing the blood from their hands with the exfoliant of insufficient excuses.

Davey Moore, at Dodgers Stadium on March 21, 1963, was defending the world featherweight title (newly fractioned between the WBA and WBC) he took four years earlier from Hogan Bassey, who himself had claimed the belt vacated by Sandy Saddler, who in turn had traded the championship back and forth over the course of four devastating and mean-spirited fights with the legendary Willie Pep.

His bout with Cuban expatriate Ultiminio “Sugar” Ramos fell in the middle of a triple-header of championship matches broadcast by ABC, a television first.

Fellow Cuban exile and new welterweight title-holder Luis Rodriguez wished his countryman Ramos well in his endeavor, himself having just unseated reigning champion Emile Griffith. The third and final fight was to feature Raymundo “Battling” Torres and Roberto Cruz competing for the vacant WBA light-welterweight belt, which Cruz would claim with a first-round knockout, only to drop it to future hall of famer Eddie Perkins in his first defense three months later. A featured championship bout on national television at Dodgers Stadium was, for Moore, a far cry from the Olympic Auditorium where he not only won his title but paid his dues, earning the reputation around East Los Angeles as ‘The Mexican Killer’ for dispatching no end of local Latin American fan favorites, “all the while dodging bottles, rocks, firecrackers, and flaming newspapers”, wrote Los Angeles Review of Books columnist David Davis.

Moore dropped out of school at fourteen to participate in amateur matches and enter the Golden Gloves tournament by fraudulently passing himself off as sixteen. 1952 was a banner year for David as he married his teenage sweetheart Geraldine, won the AAU National bantamweight championship, and earned a trip to Helsinki, Finland to represent the U.S. Olympic squad (even if he returned home undecorated) along with gold medal winning middleweight (and future heavyweight champion) Floyd Patterson, as well as heavyweight Ed Sanders who had been awarded an odd second round (of 3) decision over Sweden’s Ingemar Johansson who was disqualified for “lack of effort”. The shamed Johansson went on to both win the world title from-and lose it back to-Patterson in their classic trilogy seven years later. Sanders would die during surgery hours after being knocked out in a 1954 match against New England heavyweight champion Willie James.

At the time of his Dodgers Stadium date with “Sugar” Ramos, Davey Moore began disclosing his wishes to begin tapping the brakes on his career, slowing down to a sooner than later retirement so that he could enjoy quality time with his five children Denise, Ricardo, David, Lynise, and Davia in the Columbus, Ohio home he had purchased where he could also finally indulge guiltlessly in Geraldine’s amazing home cooking.

Ramos was one of a few dozen Cuban boxers, managers, trainers, and promoters who opted to leave their birthplace after being presented with an ultimatum by Fidel Castro. The redrafting of the Cuban constitution in the wake of the ousting of corrupt, western-friendly president Fulgencio Batista by a rebellion of Marxist-Leninist guerillas led by Fidel, his brother Raul, Camilo Cienfuegos, and an Argentinian physician named Ernesto Guevara better known by his revolutionary name Che, included the addition of a provision called National Decree 83a. This clause barred Cubans, world renowned for their proficiency at boxing and baseball, from participating in professional sports, being that they have the very un-Socialist tendency to “enrich the few at the expense of the many.” The nation’s boxers were free to go (with the understanding that they were never to return) or else accept suitable employment provided for them by the government should they decide to remain behind. For some, the choice between abandoning either their home or their dream was a necessary, if not easy, one to make.

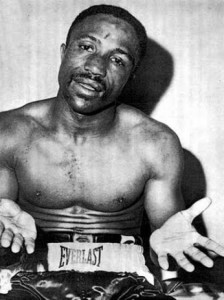

Hoping to travel in the footsteps first laid down by the great Eligio “Kid Chocolate” Montalvas, Ultiminio (meaning ‘final’, he was to have been the last of his parents’ eleven children, until they had yet another. “They couldn’t help themselves,” he would laugh) took up boxing when he was only twelve and, not unlike Davey Moore, goosed the truth in order to accelerate his ambitions and turn pro at fifteen. Fighting consistently, successfully, and happily in the capital city of Havana, Ramos strung together eleven consecutive victories, nine by knockout.

He was two years removed from fleeing Cuba and another two and a half still from his fateful fight with Moore when tragedy struck Ultiminio for the first time. The greatly overmatched Jose Blanco (4-8, knocked out five times going into the bout) soon after died from brain injuries sustained from being hammered to the mat during the closing minutes of their eight-rounder. Reversing the course of Castro’s pre-revolutionary line of travel, Ramos sought refuge in Mexico City, where he now boxed and called home, before making his American debut, thirteen months prior to fighting Moore in Dodgers Stadium, with a 9th round TKO over Eddie Garcia in the Olympic Auditorium.

Scheduled for March 16th, the Moore/Ramos fight was delayed first by fractious negotiation and then by foul weather. The Olympic wouldn’t do for the scale of the promotion that former heavyweight champion Joe Louis and other investors imagined for this showdown, but when efforts to secure the larger Los Angeles Sports Arena fell through, Miami was considered as a plan-B only to have it move back to the Golden State. With the ring positioned above the pitcher’s mound, Dodgers Stadium would play host to the event which boasted a bill including the Griffith/Rodrigues and Cruz/Torres championship matches as well. A superstitious-minded person may have been inclined to view the rain and wind storm of biblical proportion that pounded the west coast and set the fights back five days as some sort of cautionary forewarning. As pensive as he was petite, Davey Moore, the five-foot-three “Little Giant”, nevertheless bided his time by reading the Bible in between some extra workouts and sparring sessions.

“Sugar” Ramos conducted public exhibitions at the Hotel Alexandria where many boxing insiders and laypeople alike took note of how susceptible he seemed to being hit by right hands. Because that was the heaviest weapon in his arsenal, Davey had every reason to be as confident as his prediction of a knockout made evident, though he demurred in picking a particular stopping point as Cassius Clay (not yet Muhammad Ali) was so fond of doing. “I’ll take any round,” he said.

Clay’s trainer Angelo Dundee co-owned the famed 5th Street Gym in Miami Beach with his brother Chris who was a regional boxing promoter. Angelo made frequent talent scouting trips to Cuba and had been in Havana three days after Castro’s revolution. Prior to conducting Clay to the heavyweight title worn by Sonny Liston, Dundee had guided the great Carmen Basilio to welterweight and middleweight titles (highlighted by an improbable and epic victory over legendary Sugar Ray Robinson) and had been Luis Rodrigues’ trainer up to, including, and beyond his win over Emile Griffith earlier that evening. Dundee returned to the Dodgers Stadium ring, now working Ramos’ corner and looking to add another champion to his stable. Which he would, but at what a cost. Ultiminio established an early lead and commanded the attention of the announcers and spectators, to say nothing of Davey Moore himself, with two consecutive hard rights in the second round. A playful and respectful gesture was repeated by the two competitors in the early going whereby they would gently brush their gloved hands across one another’s heads as they retreated to their corners.

The fourth round saw several spirited exchanges between which the commentators remarked upon Moore’s horseshoe moustache which was uncommon enough in the early 60s that California was one of only a handful of states that allowed such a facial affectation. Much more ado concerning the heavy beard worn by Roberto Duran was instigated by Sugar Ray Leonard and none other than Angelo Dundee, who replaced Dave Jacobs as the trainer of the once and future welterweight champion, in the days leading in to their soon-to-be infamous ‘No Mas’ rematch. Referee George Latka ruled Moore’s fifth-round fall a push but, as action continued and intensified, Ramos knocked Moore’s mouthpiece out with a stunning right uppercut. Davey quickly collected both his missing gum shield and rattled senses, battling back with a flurry of effective blows of his own. It was during the brief rest period bridging the fifth and sixth rounds that the TV announcers pondered the sustained durability of both fighters in direct relation to the punishment being meted out to that point, speculating that something had to give which would prevent them from lasting the distance. Swelling on Moore’s cheekbones became more pronounced in the sixth round and by the time he sat back on his stool, blood could be seen inside his mouth as it hung open to aid in breathing that was now far more labored.

Things continued to go downhill for the champion as Ramos peppered him with a barrage of quick jabs that backed him into the ropes, until Moore was able to struggle back up the proverbial mountainside by firing away from close range, battling back to reclaim the hard-won advantage which he carried into and throughout the eighth which ended with both men simultaneously connecting with over-hand rights, Ramos’ corner applied smelling salts as Dundee attempted to talk his struggling fighter back into coherence and compliance.

Their combined efforts certainly proved successful in revitalizing Ramos who, although looking worse for wear with the flesh beneath both eyes puffing up considerably, broke and bloodied Moore’s nose with one of those relentless left jabs, staggering him badly in the closing seconds before the bell sounded ending the onslaught the ninth round had devolved into.

An icepack was held to the left side of Davey’s tilted head while Ramos was still standing, nodding while accepting his instructions from Dundee. There was no indication of impending peril and Moore was still giving as good as he got in the first half of the tenth, rocking Ramos momentarily with a left lead. With one minute left, Ramos’ attack spun Moore around and put him down to one knee which should have been, but was not, deemed a knockdown due in part to the fact that Moore bounded instantly back to both feet. He would remain upright for fewer than five seconds, however, as three long left jabs detonated upon his jawline, taking Davey’s legs right out from under him, striking his neck on the rigid bottom rope as he fell.

After receiving a standing eight-count, Moore was twice pummeled through the ropes and nearly out of the ring, but finished the round on his feet.

Ring announcer Jimmy Lennon Sr. entered the squared circle and called for the microphone which he used to inform the crowd that the fight was being stopped “on advice of the champion’s corner” and that, indeed Moore was champion no longer as Ultiminio “Sugar” Ramos had claimed the world featherweight title. Pandemonium ruled as the heavily Latin American audience acknowledged the second change of hands of world championships that evening into the possession of Cuban fighters by erupting into chants of “Arriba! Arriba!”

Broadcaster Steve Ellis leapt onto the ring apron, straddling the slim boundary the ring ropes provided from the chaos within and without, attempting to lure Ramos and/or Moore over for the traditional post-fight interview. There followed a brief back-and-forth with Ultiminio through his translator, ending with him answering the query of whether he was glad to be out of Cuba by shouting exultantly, “Yes, I’m happy!”

Growing impatient (and, viewed in retrospect, most insensitive) Ellis implored everyone within earshot to fetch the ex-champion. “Or am I asking too much?” he sulked in mounting frustration. “It just wasn’t my night tonight,” Moore said when he finally surfaced. A white towel draped over his head and eyes cast down to the ground, Davey was bent double over the second strand, arms crossed over one another to support the sagging structure of his broken body. “I don’t think he can lick me,” was his retort to Ellis’ proposition of a rematch. “I think I can knock him out,” he continues while bystanders push their way past, jostling Ellis who checks his watch and lifts Moore’s chin with middle and index fingers to coerce some semblance of eye contact.

While speaking in his dressing room to, among others, Sports Illustrated writer Mort Sharnik (who would later become an influential executive at CBS where he would script the father and son narrative which initiated the love triangle between the network, viewing audience, and Ray “Boom Boom” Mancini), Moore began complaining of a headache to his manager Willie Ketchum, cradling his splitting skull in agony before suddenly slumping into unconsciousness. Davey Moore was rushed to White Memorial Hospital (not far from another facility where heavyweight contender Alejandro Lavarante lay in a coma resulting from a fight with John Riggings six months earlier from which he would never emerge and expire the following April) where the medical staff diagnosed inoperable swelling at the base of his brainstem.

He died two days later.

The Vatican denounced boxing as “morally illicit”. California Governor Pat Brown advocated for a ban of “this so-called sport”, though all that would culminate from this would be that the State Athletic Commission ordered a fourth strand to be added to the set of ring ropes which would all from then on be more heavily padded.

Boxing, and life as it does, would go on. Geraldine buried her husband and raised their children as a single mother. Bob Dylan wrote and played live his pugilistic condemnation set to verse. Pete Seeger would perform it on occasion and fellow folk singer Phil Ochs recorded a ballad of his own, simply titled “Davey Moore”. Ultiminio Ramos appeared, in print anyway, to be both sorrowful and indignant in the same thought process when lamenting, “Why did he have to die? It was my night, my glory, I won fair and square. Then he dies and nobody remembers that Ramos fought a good fight and won.”

“I work hard and beat him,” he said. “I am not a killer.”

Later in life, he would sound a more contemplative and compassionate tune.

“It was something very hard, but as a professional boxer, I had to go on and overcome the situation.” In a popular refrain that has become all too common in the fistic songbook, repeated by survivors of fatal prizefights, like performing ablutions by way of some mournful mantra which, chanted enough times and with the proper degree of righteous virtue, will summon peace and absolution, Ramos theorized that “what happened to him could have happened to me.”

“No one killed Davey Moore,” said his widow Geraldine when asked what she thought about Bob Dylan’s exculpatory ballad about her husband’s death. “You know, nobody killed him. It was a tragic accident and nobody was to blame.” These words were directed toward the distinguished looking gentleman standing nearby dressed in a black suit, white hair peeking out from beneath a Panama hat, who had traveled from Mexico City to be in Springfield, Ohio on a sunny Saturday in September 2013. The occasion which reunited Ultiminio Ramos and Geraldine was the dedication of an eight-foot tall bronze statue of Davey Moore.

To her immense credit, Geraldine never harbored ill will toward Ramos, her sentiments that day echoing ones spoken between the two of them in White Memorial Hospital the night of the fatal fight. “Lo siento (I’m sorry),” was the only thing Ultiminio could think to say to the woman whose husband lay in a coma because of the damage he had inflicted on him.

“You are the lucky one,” she had told him. “It was God’s act.”

It was the discovery of a photograph from that night in a family photo album which would assist Davey’s son Ricky in later processing what to him had then seemed inconceivable. The image of “Sugar” Ramos sitting in a chair outside his dad’s hospital room, head in hands, and crying uncontrollably helped him comprehend the fact that his mother simply refused to feel any animosity. Ramos met and talked with the children, presented Geraldine with a colorful bouquet, and accompanied her to Davey’s grave on which he placed another floral arrangement.

“It was beautiful for me because I saw what I needed to see,” Ultiminio expressed with gratitude through his interpreter. “I was at ease and I wasn’t afraid. There was peace and tranquility.”