Marvin Camel, First and Two-Time Cruiserweight Champion of the World

By Chris “Man of Few Words” Benedict

By Chris “Man of Few Words” Benedict

Throughout the four-day long festival of fistic commemoration that culminated in the enshrinement of the International Boxing Hall of Fame’s class of 2015, Canastota, New York played host-as it does each June-to inductees and invited visitors representing boxing’s past, present, and future, not to mention fight fans from all points on the map. Dozens of familiar faces meandered around the museum grounds on foot or were whisked past in golf carts by red-shirted events staff, and then exchanged their daytime casual wear for more formal attire to attend the cocktail hours and dinners, all-hours nightcaps at Graziano’s, and finally Sunday’s Parade of Champions through Carmen Basilio’s hometown leading up to that afternoon’s ceremony.

Riddick Bowe was impossible to miss. Ray Mancini attracted a sizeable crowd wherever he went of both guys and girls jockeying for position for an autograph and a photo with “Boom Boom” and he would not budge until all requests had been obliged. Amir Khan and Sergio Martinez similarly stirred up no short supply of excitement among gents and ladies alike, and Heather “The Heat” Hardy had more than a few male hearts aflutter before the revelry was over. The Brothers Spinks, 1976 Olympic Gold Medalists and former World Heavyweight Champions Michael and Leon were present once again to participate in the weekend’s various activities. Micky Ward and Dicky Eklund raised a little hell Lowell, Massachusetts style. Gerry Cooney towered above the masses and the still raging 93 year-old Jake LaMotta shuffled along in a cowboy hat.

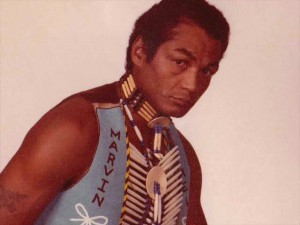

One bespectacled individual, though, standing 6-foot-2 and wearing a wonderfully ornate beaded necklace, had even the most devoted boxing aficionados initially scratching their heads. Getting a glimpse at his name tag would have been helpful in avoiding an embarrassing faux pas but, before you could come close enough, all doubt had already been erased. For no sooner would he round a corner and encounter a gathering of curiosity-seekers than the tall, lanky stranger would be unfamiliar no more after proudly announcing his presence. “Marvin Camel, first and two-time Cruiserweight Champion of the World!”

Prophetically, Marvin was given a 5th grade school assignment where his class was asked to speculate upon their future vocations. He simply wrote, “I want to be champ of the world.” Camel’s middle name is Louis in honor of “The Brown Bomber” and his brother Robert was bestowed with Liston which needs no further explanation. Marvin’s father was an African American Navy sergeant and amateur boxer named Henry who compressed his patronymic from Campbell into Camel and Alice Nenemay, his mother, was a full-blooded Pend d’ Oreille Indian and raised her boys as members of the consolidated Salish Kootenai Nation on Ronan, Montana’s Flathead Reservation.

Henry founded the Desert Horse Boxing Club where a young Marvin cut his teeth whether he liked it or not. Fortunately, like it he did because his father, a stern disciplinarian, left him little choice in the matter. “It was either get in the ring or face the belt,” Marvin would later recall. At the age of 12, he was thrown into a contest against Allan Burland who was two years older and vastly more experienced. That beating was a rude awakening that opened Camel’s eyes to what lay ahead should he pursue boxing beyond adolescence. Many youths may have understandably grown exasperated and quit on the spot, but Marvin was made of tougher stuff. Not only did he play both offense and defense on the Ronan High School football team, but Marvin also ran track and was once accidentally spiked in the calf during a meet. Stitched up on the sidelines in between events, he went on to run a leg of the relay.

Marvin managed to receive his diploma despite poor grades and worse attendance, showing up for only about ½ of his senior year but putting in a memorable appearance at the graduation ceremony. “I had no cap, tassel, or gown,” Camel says in Brian D’Ambrosio’s biography Warrior in the Ring. “I jumped up and shadow-boxed, waved, and walked on out.”

When he was but a lad of sixteen, Marvin and a friend went on a high-speed joyride after smashing a beverage center window and stealing a six-pack of beer and his life story nearly ends right here. His companion lost control of the car which rolled over and paramedics responding to the accident originally pronounced Camel dead at the scene. Fortunately, a two-week hospitalization, another fortnight in jail, and three years’ probation would amount to the worst of the fallout from Marvin’s transgression.

It is estimated that Camel engaged in 250 amateur bouts, many of which were smokers that took place before sparse collections of observers in VFW or Knights of Columbus halls. One of his victories as a novice prizefighter came over soon-to-be Olympic Gold Medalist (the only boxer so decorated on the 1972 U.S. squad) Sugar Ray Seales at St. Anthony’s Gym in Missoula, Montana in December 1971. The following year, Camel lost a split decision in the middleweight finals of the National Golden Gloves to Marvin Johnson who would travel to the tragic Munich games with Seales, winning a bronze medal and moving forward to world championship glory in boxing’s light-heavyweight division.

Around this time, Marvin went to work as a pinball repairman for Elmer Boyce’s Montana Music Rentals which not only earned him some pocket money but provided a makeshift gym tucked away in the rear of the warehouse to work out in. With Boyce acting as his employer, manager and promoter, Camel would rise at 5:30 for 6 miles of roadwork, put in a full day fixing pinball machines in pool halls, bowling alleys, and redneck honky-tonks all across Montana where the inebriated patrons belligerently called him “Chief”, and return in the evening to jump rope, work the speed bag, and shadow-box for 15 rounds all while listening to Credence Clearwater Revival.

Initially fighting professionally only three times over the course of 18 months, he made quick work of each opponent, dispatching Joe Williamson by TKO in the first round of each man’s 1973 debut following the last of three knockdowns. The frequency with which Marvin took to the ring increased dramatically thereafter as he would become a house fighter of sorts at Las Vegas’ Silver Slipper while compiling a spotless 14-0 record. Vegas to Camel was an alien world and he felt like a stranger in an even stranger land, sleeping in back of his van in the parking lot of Johnny Tocco’s Ringside Gym just off the strip. Marvin was awoken one night by someone attempting to break into the van and, not unlike The Dude in “The Big Lebowski”, Camel’s greatest concern was not for his personal safety but for his Credence tapes.

Three days after the nation’s bicentennial-on July 7, 1976-Camel would square off in Stockton, California against 11-1-1 Matt Franklin who would become better known as Matthew Saad Muhammad following his defeat of NABF light-heavyweight champion Marvin Johnson (almost one year later to the day) and subsequent conversion to Islam. Both men scored knockdowns but the bout would last the distance with Camel suffering his first career loss when Franklin was awarded the split decision by the most threadbare of margins.

They would reengage three months later at Missoula’s Adams Field House, bookending a pair of points wins for Camel over Johnny Townsend. Judge Joe Antonetti scored the fight a 96-96 draw while Billy McFarland had Marvin winning by two points and referee Bob Foster saw it 100-91 in favor of Camel who won the majority decision, one which Matt’s manager Frank Gelb suspected was influenced by hometown advantage. Gelb demanded to see the scorecards only to learn that no one from the Montana Board of Athletics was left in the arena by the time his protest reached a fever pitch with the exception of a secretary who declared a no-contest pending further review. It took only two days for Marvin Camel’s victory to be legitimately upheld by the Athletic Board and officially entered into the record books.

Taking the controversial nature of both fighter’s wins into consideration, a rubber match between Marvin and Franklin would have been not only warranted but warmly welcomed. Unfortunately it was not to be, relegated to the could-have-been, should-have-been imponderables littering boxing history.

A 6th round TKO setback to Danny Brewer on June 29, 1977 in Seattle due to excessive abrasions around Marvin’s eye would be his only defeat for more than three years since his first to Matt Franklin and he would pick up the vacant NABF Cruiserweight belt along the way by toughing out a unanimous decision over Bill Sharkey. Convicted of a manslaughter charge in 1971 for which he served three of ten years, Sharkey himself would later be the victim of what remains to this day a cold case murder-shot, stuffed into the trunk of his repurposed NYPD cruiser, and driven to a secluded area of National Park Service land 15 miles from his hand-built log cabin in the Poconos where he was set on fire and discovered on October 24, 1998.

Now 35-2-1, Camel would be matched up in his first 15-round fight on CBS’ Sports Spectacular against Mate Parlov, Gold Medalist at the 1972 Munich Olympics and 1974 World Championships in Havana, in his birthplace of Split, Croatia to decide the WBC’s inaugural World Cruiserweight Champion on December 8, 1979. The tournament final between the power-punching southpaws was declared a majority draw when judges Sid Nathan (143-143) and James Brimmell (144-144) both saw it even. Referee Raymond Baldeyrou egregiously gave the 147-142 edge to the clearly outworked Parlov. The decision was so wildly unpopular that the Yugoslavian crowd threw roses at Marvin’s feet after the scores had been read and the following day’s sports section of Belgrade’s Politika Ekspres proclaimed Camel the true victor. Even Parlov himself conceded that “If the match was held in the United States, I would’ve lost.” This was all cold comfort to Marvin who repeated endlessly to himself, “Fifteen rounds for nothing.” All of which meant that Marvin and Mate would reacquaint themselves with one another three and a half months later on a special night at Caesars Palace.

Alexis Arguello and Thomas Hearns both fought (and won) on March 31, 1980’s undercard in Vegas and Larry Holmes would defend his WBC World Heavyweight title against Leroy Jones in the main event. That fight would be part of a prime-time ABC simulcast with three championship matches from other locations: “Big” John Tate vs. WBA World Heavyweight Champion Mike Weaver and Eddie Mustafa Muhammad’s 11th round win over WBA World Light-heavyweight title-holder Marvin Johnson from Knoxville, TN as well as Dave Green challenging Sugar Ray Leonard for his WBC World Welterweight belt from Landover, MD.

The co-feature was the sequel to Mate Parlov and Marvin Camel’s quarrel for the WBC World Cruiserweight title. With the legendary Eddie Futch working his corner, Camel neutralized Mate’s size and strength by working out of a crouch and left no doubt about the outcome this night, surviving a late scare after a Parlov right jab opened a grisly cut on his eyelid to distantly outpoint his opponent, settle the score, and claim the world championship-the first for a cruiserweight, for a Montana resident and, most significantly, for a Native American. It would be Parlov’s last fight.

Marvin’s reign would last a little less than eight months. He had signed to face Victor Galindez but canceled when he was diagnosed with a detached retina during a pre-fight exam and only circumvented the indignity of having his boxing license revoked by undergoing surgery using a pseudonym and asking ophthalmologist Matthew Bernstein to not submit his findings to the boxing commission. Despite having grave reservations about his decision later in life, Bernstein relented to Camel’s wish and Elmer Boyce fabricated a story involving an accident having occurred while Marvin was repairing a pinball machine. Instead, he would be paired off with Carlos De Leon at the New Orleans Superdome on the same night as the infamous “No Mas” fight between Roberto Duran and Ray Leonard. Don King served as the event’s carnival barker and, never a shrinking violet in the face of unsavory gimmickry, asked De Leon to pose for promotional photos and appear at the press conference holding a ceremonial knife with which to supposedly “scalp the Indian”. Carlos wisely declined. By the time De Leon had gotten through with Marvin, however, it would look as though he had taken a hatchet to Camel’s face. A gruesome series of lacerations encircled Marvin’s right eye and De Leon would take his belt home in the bargain, the beneficiary of a relatively slim majority decision (judge Ray Solis scored the bout a 145-145 draw).

After parting ways with Elmer Boyce, Camel rebounded with a four-fight win streak in 1981, collecting Willie Shannon’s USA Nevada State Cruiserweight title as well as the USBA version off of Bash Ali. His February 24, 1982 rematch with the 31-2 defending WBC Champion Carlos De Leon at the Playboy Hotel and Casino on the Atlantic City boardwalk proved to be an unsuccessful campaign, culminating in an 8th round TKO.

The newly formed IBF held its to-be-determined Cruiserweight title fight on December 13, 1983 in Halifax, Nova Scotia, the hometown of former Canadian Light-heavyweight Champion Roddy MacDonald (having lost the belt to Donny Lalonde back in July) where Roddy would be caught by a disabling body shot in the 5th round by Marvin Camel. Referee Bobby Beaton initially declared it a low blow but was instantaneously overruled by IBF director and legal counsel Alvin Goodman who awarded the TKO victory and freshly minted title to Camel. This would prove to be the polar opposite of his experience in Croatia. Mirroring what had happened to Marvin Hagler when he had taken the Middleweight title from Alan Minter in London, Canadian fans showered Marvin Camel with obscenities and debris, forcing him to flee like a thief. Back home there was pitiful consolation to be found. Just as Sonny Liston had learned by hard experience how little the people of Philadelphia cared for him when his plane touched down following his triumph over Floyd Patterson for the Heavyweight championship, there were few if any well-wishers to greet Camel at the Missoula Airport. Uneasy lies the head that wears a crown.

His sovereignty in the IBF would last only slightly longer than his short-lived autonomy over the WBC Cruiserweight division. Ten months later Marvin, who trained with Jinks Morton and sparred with Marvin Johnson in preparation, would defend against undefeated (20-0) Lee Roy Murphy at Metra Park in Billings, Montana. Murphy had captured the 1979 National Golden Gloves Light-heavyweight title which qualified him for the 1980 Olympic team but, due to the United States’ boycott of the Moscow games, that potential dream would go unrealized. Not so his quest for a world title, though it was no easy feat. Despite splitting open old wounds over Camel’s right eye in the 5th and dropping the champion in the 8th, Camel nevertheless established and maintained a solid lead going into the 14th when a Murphy right carved a gash above Marvin’s left eye nasty enough that he was disallowed from going out on his shield and relieved of his title by referee Dan Jancic.

Plagued by persistent eye problems not to mention harboring feelings of resentment for and alienation from the boxing community and-worse yet-his home state of Montana, Camel would not fight again for a year and a half although his record reflects the unpleasant but honest truth that he would have been well suited to an early retirement. Instead, Marvin plodded dutifully forward until 1990, winning only two of his last eleven contests with notable losses coming as a first-round knockout victim to a young Virgil Hill who was a mere four months away from winning Leslie Stewart’s WBA Light-heavyweight title and via 6th round TKO to Joe Hipp, a member of the Blackfoot tribe just across the Continental Divide from Camel’s Flathead Reservation. Hipp would later make history as the first Native American to challenge for the Heavyweight Championship, against WBA belt-holder Bruce Seldon on the undercard of Mike Tyson’s 1995 comeback against Peter McNeeley.

Things would come full-circle in a weird way for Camel when his last opponent (and conqueror) would be Eddie Taylor who also went by the moniker Young Joe Louis, a bastardization of Marvin’s middle-namesake. Camel and Mate Parlov would be reunited at the 2006 WBC Convention in Croatia where the old antagonists would form a bond not uncommon to those who had been through the hell of battle together and could now leisurely swap combat stories and compare war wounds with a good and comforting laugh. Both men were awarded honorary championship belts which, for Marvin, would replace the one spitefully buried in an undisclosed location by his first wife Sherry. Camel would regretfully learn of Mate’s death from lung cancer two years later from a co-worker at a Circuit City in Florida where he now resides-where he stocked shelves and worked security-who recognized Marvin’s name while reading Parlov’s obituary on their computer. He hasn’t been able to completely shake the overwhelming emotion that a little piece of himself died that day too.

His new wife Norma wrote in a letter to me recently that they both very much enjoyed their trip to Canastota and that they were already initiating plans to return. Perhaps to someday look upon his very own plaque. If Camel’s credentials (45-13-4, 21 KOs) seem spotty contrasted against the always debatable-one might argue questionable-Hall of Fame criteria, you may might pause to consider the sentiments of 2015 enshrinee Ray Mancini whose eligibility extended back for nearly two decades (1997 surpassing the requisite 5-year removal from his last fight against Greg Haugen), and yet was only submitted for approval on this past year’s ballot. 29-5 admittedly may not leap off the page as a glorious or even obvious Hall of Fame-worthy record. Mancini himself confessed near the close of his Ringside Lecture on Saturday afternoon (prefacing his remarks with the dismissal of false modesty) that he considered himself to be merely “a good fighter” who had “some great nights”.

That said, it would be great-and, in my humble opinion, well deserved-if one year in the not too distant future Marvin Camel could revisit Canastota and not have to vocally publicize his own identity (though he would very possibly be happy to do so regardless) but could leave the task to the International Boxing Hall of Fame official who welcomes each new inductee up to the podium of informing the multitude of pugilistic enthusiasts that the exuberant gentleman now accepting his gold ring is “Marvin Camel, first and two-time Cruiserweight Champion of the World.”

[si-contact-form form=’2′]