The Master & the Apprentice Or When Bobby Met Charley

[AdSense-A]

Bobby Lippi was the son of Italian immigrants to Pittsburgh. Growing up he often found himself in trouble, usually of his own making. The fact that his dad, Paul, was a well-known cop in the city, didn’t prevent young Bobby from hanging around with the regular folks who inhabited the hill district of the city.

In the summer of 1942, Bobby fell victim to one of his own practical jokes, and came to realise that a lump of tar is not an easy thing to remove from one’s hair—unless the hair comes out too. Sporting a bald head—likely designed for punishment, as much as necessity—Bobby became popular with the number-players and runners around Bedford and Wylie Avenues.

The local number joint was a few yards down from the corner of Manila and Bedford Avenue where Bobby and his friends hung out. People passing on their way to the joint started rubbing his bald head for luck, which was a source of great laughter for Bobby’s pals until one day some guy gave him 50 cents as a reward for the good fortune he had brought. Bobby started hanging out at the top of the alley where the number joint was situated, just in case anyone else wanted to rub his head for luck and pay him for the privilege. Eventually, he got to know most of the faces and names of the constant flow of people that went in there to place their wager and the guys that operated the place also befriended ‘Bald Bob’. When the joint was forced to move a couple of blocks down the street, he was paid 50 cents to direct the traffic.

Bobby then graduated to taking the slips and the stake money from the people that passed by on the street and running it down the alley to the number joint. He was paid for running and, if anyone got lucky, he was tipped occasionally. With an allowance of 16 cents per week from his parents it is not difficult to see how this easy-money would have appealed to an impressionable teenager.

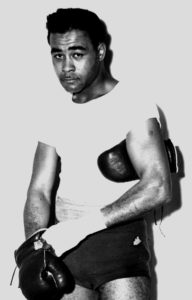

Given the fact that he often had other people’s money on him, it was a good thing Bobby could handle himself. He had a short, but successful career as an amateur boxer, had won a novice championship and he was proud of the reputation he had as a scrapper. With his dad growing tired of his fighting with other number-runners—and troubled by his likely career-path—Bobby was informed that if he was going to continue fighting he should at least earn some money for it. While the career of a professional fighter was not ideal, it was at least a way of getting him away from the racketeers who were running the numbers game. Paul also told Bobby that if he was going to commit to it, then he should do it properly. Fortunately, Paul Lippi knew a local fighter of some repute who was now back in Pittsburgh after a stint on the West Coast—Charley Burley.

One day, while the Burleys were enjoying lunch in their home at 1712 Bedford Avenue, Paul Lippi swept in. Without speech or ceremony, he pushed his son Bobby towards the table. “Here he is,” he told Charley, before marching straight back out of the door. Charley motioned for Bobby to sit down but said nothing. “That’s how my boxing career really started.” Bobby remembers. The Burley home had once been the Lippi home and Paul Lippi was instrumental in getting the landlady to rent to Charley and his family. She didn’t want to at first because she didn’t want a black family living there. Paul Lippi told her that is she didn’t rent to Charley he could make things difficult for here with the city council.

When he initially went to the gym to train with his mentor, the first thing that Bobby noticed was the awful condition of Charley’s boxing shoes, “He had the worst shoes. They looked like they had been worked down a coal mine.” Bobby said. When Bobby made the mistake of putting  brand new white laces in his own boots, Charley went to work on dirtying them up for him. While it may have been a case of ‘look the part and feel the part’ for Bobby Lippi, Charley Burley was of the opinion that ‘less was more’ and, as Bobby Lippi recalls of his mentor’s Spartan attitude, “Anything that could spoil you was out”. Bobby had great memories of the gym and the boxing education he received. “I was cocky. I had won some two-bit championship, but I knew nothing. When I first went to the gym Charley would let Eddie Hines and them guys beat my brains in.” Charley told Bobby, “You don’t know how to fight kid, but you’re going to find out.” Bobby said, “Eddie Hines used to rip me, he was a good boxer, no puncher, but this kid had all the combinations, like a little Sugar Ray Robinson. Charley would put him in with me because he had no power, none.” Bobby said that, due to Hines’ lack of power, he had no respect for him. “He couldn’t hurt me, but trying to catch this guy. I mean he was swift.”

brand new white laces in his own boots, Charley went to work on dirtying them up for him. While it may have been a case of ‘look the part and feel the part’ for Bobby Lippi, Charley Burley was of the opinion that ‘less was more’ and, as Bobby Lippi recalls of his mentor’s Spartan attitude, “Anything that could spoil you was out”. Bobby had great memories of the gym and the boxing education he received. “I was cocky. I had won some two-bit championship, but I knew nothing. When I first went to the gym Charley would let Eddie Hines and them guys beat my brains in.” Charley told Bobby, “You don’t know how to fight kid, but you’re going to find out.” Bobby said, “Eddie Hines used to rip me, he was a good boxer, no puncher, but this kid had all the combinations, like a little Sugar Ray Robinson. Charley would put him in with me because he had no power, none.” Bobby said that, due to Hines’ lack of power, he had no respect for him. “He couldn’t hurt me, but trying to catch this guy. I mean he was swift.”

Bobby would often wonder what was going on as Eddie Hines constantly popped him in the face with a rapid-fire jab and Charley would tell him, ‘Well, you got to learn.” It seems it was just as bad when they put the young apprentice in with Bobby Malone, “Bobby Malone had power and didn’t give a damn who he used it on, he was a mad man.” Bobby remembers, “Charley had to knock him out because he tried to show him up in the gym. Charley knocked a few of them out—even Ossie Harris [a childhood friend of Burley]—he knocked Ossie Harris out twice, once in the ring and once in the gym. Ossie wasn’t convinced that it was a genuine knock out the first time, so Charley had to do it to him again.”

According to Bobby, the sparring—though brutal at times—was much more fun than the monotonous training that Charley Burley put him through. Drill after drill of foot and body-positioning repeated over and over—all designed to teach effective defence as well as offence:

“I had to learn that you couldn’t just go running in there and I had to learn that a right hand wasn’t just to punch the other guy’s head in. The right hand is kept high to stop the left hooks. The same with the left jab, my elbow was so sore! I had to SNAP that jab out, not drop it. If you dropped it BAM, an overhand right came at you. So you kept it up. It went out, it came back and when it came back, a hook came right off of it.”

Bobby said that Charley had him think of his arms as being real loose, like long strands of thick, rubber cord. Each of his fists had to be a rock on the end of the rubber cord. “When I finally got it, it was amazing. It was like having a pool ball in a sock. You understand? That’s some weapon.”

As well as learning the finer points of fighting, Bobby also got to learn about the realities of professional boxing in 1940s America. He had one particular example that was etched in his memory which relates to how Charley Burley was avoided by many welterweights and middleweights of the day:

“Being black and everything, that was only half the story. The other half of the story is Charley was an honest prize fighter, he would not make deals, he would not carry a fight, you’re gonna’ beat him you’re gonna’ beat him straight up. He knew if he carried a guy they’re gonna’ steal the fight off him…. and he wasn’t gonna’ let that happen, you had to BEAT him.

“We went to Cincinnati where he fought Dave Clark, (Sept 4th 1945). We stayed at Ezzard Charles’ hotel. Back in them days I didn’t know nothing about racism and classes and how that worked. You knew it was there but you never saw it in action, you know what I mean. So, we get into Cincinnati early in the morning and we go down to the Cotton Club for breakfast and what have you. So, it’s ‘Charley Burley the celebrity’ and all that crap, and the owners of the Cincinnati Reds come in to have their photographs taken with Charley Burley you know?

“The weigh in is supposed to be at 11 O’clock in the morning, they changed the time to 1 O’clock in the afternoon. That’s to mess up Charley’s eating habits see, and then they started on me. ‘What was I doing going into Ezzard Charles’hotel ?’—that was a black hotel. I was not allowed to sit out in the Cotton Club I had to go back into the kitchen to eat, I mean this is ridiculous. Then some gangsters came by and were trying to talk to Charley, they tried to push me off to the side and Charley wouldn’t let them, ‘cause I didn’t know what was goin’ on. And they wanted Charley to carry Dave Clark for the ten rounds. Charley said ‘No! If he can make it, fine, but I’m gonna’ knock him out.’

“So, we went back [to the hotel] and for the rest of the day, you know, lots of different people would stop and get into, use the same aggravation about me being under-age. They’d use the liquor laws and what have you, ‘cause I was 16, well I was 15 going onto 16 see.

So, that night they didn’t give us a dressing room inside the arena, they gave us the parking lot attendants office outside … all dusty and…, Charley had a beautiful, grey fedora hat! Now he’d brush it off and, now he’d put it up on a shelf and that was too dusty, so he’d dust it off again—definitely got him mad. Charley don’t say too much when he’s mad, it’s just a slow burn. So, we had to walk from the parking lot to get into the arena. When we get into the arena they’re gonna’ introduce me from the ring as Charley’s protégé. As I’m going across the ring, I tripped on the canvas—they had the canvas real loose so you couldn’t dig in, you know, for your power punches. So I have to go over and shake hands with Dave Clark—you know I didn’t even want to shake hands with Dave Clark, I was mad at him myself. You know what, they brought in 10oz gloves, not 8’s, the big ones. Bobby McKnight is in the corner and he’s trying to knead the gloves and push the padding back. Charley was mad.

“I’ll make the story short, Charley knocked him out in 1 minute and some odd seconds of the first round. People were mad because some of them hadn’t even sat down yet. And the worst part of it is that Dave Clark went on to fight Sugar Ray Robinson—they by-passed Charley. Now, Charley could have fought Ray Robinson if he’d have made a deal—he loses the first fight. Anyway, the gangsters wanted Charley to carry Dave Clark for the [betting] odds. It was rotten, it was rotten.

“You know, between Charley and my dad, I learned what the rackets were about. I stayed independent. I could have had number joints, but I would have worked for someone else.”

The boxing career of Bobby Lippi never really got going as he liked hanging around with the wrong crowd too much. In 1949 he was sent up the river for a robbery he was involved in—but, as Bobby would say, ‘that’s a whole other story’. The professional career of his mentor ended without a title, but with an induction to the International Boxing Hall of Fame (1992) and recognition as one of the greatest fighters ever. Despite the difference in age, the two remained friends for life.

*This article is based on interviews with Bobby Lippi at the Burley home in Pittsburgh in 1997 and 1999. The original account of their meeting and friendship appeared in the author’s book—Charley Burley and the Black Murderers’ Row (Tora Books, 2002)

[si-contact-form form=’2′]