Ringside Report Looks Back at Former Champion Charlie Magri

[AdSense-A]

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

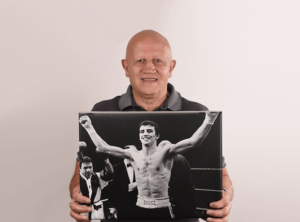

He had the look of a boxer, of a fighter with a nose that knew too many fists. As he retired and grew older, the hair left him, but the rugged looks did not. During the 1970’s and 80’s he was “Champagne Charlie”, the guy who fought with his heart on his sleeve, his guts in his mouth and left your jaw on the floor. His name in the ring was Charlie Magri, 30-5, 23 KO’s, his nickname, “Champagne” Charlie though he was born Carmel Magri. His reputation was as fierce as the nickname was supposed to be impressive. Charlie Magri was not a man to cross but his legacy in British rings is a long cast shadow that lights up more than it darkens, which impresses on the basis that he is only 5 foot 3 inches tall!

Magri was a come ahead fighter, adaptable and with little by way of defense. His approach was to wear guys down and he did that so successfully that in his thirty five fights, he was to stop twenty three opponents, not by a single devastating punch but through persistence and accuracy.

Magri was born in Tunisia and grew up with his family in the tough East End of London. It forged a man with determination and sparkle. That sparkle was evident when he became the WBC and lineal flyweight champion and his determination saw him reach his peak whilst also preparing for a life outside the ring.

His path to boxing glory took in another sport – soccer. As a young lad he played for Millwall’s youth team but his desire to fight saw him lean towards a career through the Arbour Youth Club and boxing rather than The Den and soccer.

He was to recount later in life how, when he was but eleven years old that his feet took him into the gym and he started punching a bag until a trainer told him not to punch it without gloves. That began a love affair that kept on giving and going. In no l=more than two months he was fighting in a ring.

Thus began the career of the promising amateur, Charlie Magri who won two Amateur Boxing Association (ABA) titles and four ABA senior titles consecutively from 1972 to 1977. In 1975 he won a bronze medal at the European championships before boxing for the UK in the 1976 Montreal Olympics. Magri was under immense pressure, given his ABA record and was tipped for a medal. This was the famous Cuba v USA Olympics so getting noticed if you had not the vests of either of these countries was always going to be difficult. It was pressure that saw him not progress beyond the last 16. His abiding memory – watching Sugar Ray Leonard with his lightening speed, volume and accuracy on the pads.

He returned home, won his last ABA title and then in 1977 made his professional debut under legendary British promoter, Terry Lawless.

Catching the eye of the press throughout the 70’s and 80’s, he was often referred to by his day job – a tailor’s cutter – and he certainly cut a dash in the ring. He gained the British title in only his third fight! He was also voted the best young boxer in his first year as a pro! The British title was one that he never defended. Normally, to keep the legendary Lonsdale belt – the prize for the British champion – you must defend the title successfully three times. There were not a lot of flyweights around so ten years after winning the belt, the British Boxing Board of Control gifted Magri the belt for keeps. He had by then gone way beyond British level.

There was also the way in which he had beaten Dave Smith for the British belt. He was utterly devastating and other British boxers started to avoid his calls. He was now on a different route – into Europe – though the money he was earning was never in line with what he was risking. His fee for the British title was not great – a feature of his entire career.

By May 1979 and in his 12th fight he was European flyweight champion, beating Franco Udella for the title at Wembley in his adopted hometown of London. It was the very first time that the EBU had dropped the number of rounds from 15 to 12 for the title; Magri took the belt in a split decision. For British boxers of the time the way to a world title was through British and European titles – not the international and intercontinental shapes thrown today. Magri always believed that the route he took was the pure route and many in the UK still think that following the traditional pattern gets you to a tougher stance, a more prepared advance for a world level title.

The amateur pedigree that Magri had prepared him also for facing different opponents. In an interview in Boxing Monthly he was to reflect on his professional approach, “I … was familiar with most styles. I did not need to watch DVDs of my opponents to make an assessment, that was what the first round was for.”

In a little known encounter with a fellow fighter in the 19080’s and I am grateful, for Steve Bunce’s book on British boxing over the last 50 years for the story, as a European champion he was once sitting next to Johnny Owen, a British champion. Having both just won their fights, Magri and Owen agreed to fight. Owen had a fight in America to get through first. He didn’t last the fight and died after forty six days in a coma. The Magri-Owen fight never happened as a result.

On the 15th March 1983, Magri was to take on Eleoncio Mercedes for the WBC flyweight title. The fight was stopped in the seventh round due to cuts and Magri was the world champion. There was a lot of people who thought Mercedes was not a great champion but Magri had to still do the business and he did. Becoming world champion and the lineal champ at that was huge.

It was, however, a short reign and in his first defense against Frank Cedeno the fight was stopped when Magri had been put on the canvass no less than three times in round six. Unbeknown at the time by the watching public. Magri had a condition known as blind boil behind his left ear, was on tablets and was drained in the week of the fight. He ended up in hospital and his world title ended up being driven away from his hands at the end of the fight.

He was to try and regain his crown in February 1985 when Magri was again stopped because of cuts this time, sustained by Magri when he faced former kickboxer, Sot Chitalada.

By that time Magri had regained his European crown but the lights were beginning to fade. The passing of the torch from who had been to who was going to be came in his final fight. Duke McKenzie brought the British title that Magri had relinquished into the fight whilst Magri brought his European belt. McKenzie, after Magri’s manager Terry Lawless had thrown in the towel disappeared with both at the end of the fight.

That was bitter but Lawless in his last words to Magri, in the dressing room after the fight were even harder to swallow. Having just lost and beginning to realize it all must be coming to an end, lawless had little by way of comfort. “You are going to have to get up off your arse and get a real job now,” he was alleged to have said. As pep talks go, it was hardly Olympian material.

His retiral saw a number of ventures which included a pub and sports shop but he also stayed to an extent, in the boxing game. He has coached with Ealing, Hammersmith and West London College’s boxing academy and in a recent online interview Magri was bullish enough to say that he still thought he could beat anybody! This was what attracted us all to him – that confidence in a guy who was 5 fight 3 inches tall – more than admirable!

[si-contact-form form=’2′]