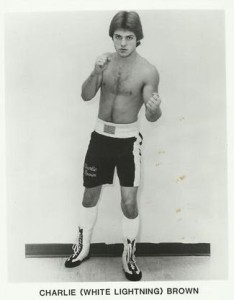

Charlie “White Lightning” Brown : Once Lightning, but Sadly Turned into Silent Thunder

[AdSense-A]

In the Spring of 1942, the artist Edward Hopper created the iconic painting “Nighthawks”. The piece depicts a bartender behind a triangular bar, a patron at the counter with his back to the observer and a young couple across the bar who seems slightly distant from one and other. It has been described as “a picture of lonely emptiness” and it has seen many incarnations over the years with the characters often replaced by singers, sports personalities and screen stars. The most popular adaptation is Gottfried Helnwein’s “Boulevard of Broken Dreams” which inserts Elvis as the bartender, James Dean as the lonely figure seated at the counter and Bogart & Monroe as the couple separated by silence. The piece is a favorite of 50’s themed diners and “cool” haunts across the globe as it encapsulates the sorrow that exists behind the star studded glare of fame….laugh and the world laughs with you, cry and you cry alone.

I often wondered why no one had adapted the piece to the world of boxing. If it’s “a picture of lonely emptiness” you’re after, you’d do worse than browsing through the pages of most fighters lives. I’d seen the line up with Arturo Gatti behind the counter, Jake and Vicki LaMotta as the estranged couple and Charlie “White Lightning” Brown as the solitary figure lost in thought. “Lost” would certainly be one of the words best used to describe Brown, whose career was punctuated by peaks and troughs so extreme that the altitude would have been a problem soaring up and spiraling down. To get a better insight into the genesis of “White Lightning”, we must go back to the Ohio State Fair of 1980.

The fair had drawn some of boxing’s biggest names over the years and, in the late 70’s and early 80’s, if you wanted a tip for the future, you could bypass the Olympic trials and get yourself to Ohio to see the very best talent on offer. For instance, the 1973 State Fair finals saw the names of Aaron Pryor, Tommy Hearns, Ray Leonard. 1975 had Tony Tucker and Tony Tubbs while 1977 was the time of Jimmy Paul, Kevin Rooney, Bobby Czyz and Lindell Holmes. But it was in 1980 that 16yr old kid named Charlie Brown would make the 400 mile trip from Illinois and be crowned King of the 132lb division with a win over Anthony Hasklins. A year later, Brown would beat Darrick Hudson in the open final to once again take the title home to East Moline. He was “found” by Don Turner and Stanley Komissar who brought Charlie to Lenny Shaw and he was signed up.

Brown was dedicated to his training and committed to his career. He had speed and a big heart and the nickname “White Lightning” was coined by two black kids who watched him train. “They said they’d never seen a white guy with such fast hands” Charlie would later recall. His career got off to off to an explosive start with a first round KO of Chester Jackson in Memphis on September 21st 1982. He followed that with big wins in such places as Miami, New Jersey, New York City, Las Vegas, Atlantic City, Iowa, New Mexico and North Carolina. With each win, the fan club grew and the train just kept on rolling, Pennsylvania, Ohio, Virginia, California, “White Lightning” was proving to be just as big a draw outside of the ring as he was inside and red flags were flying high for those in his corner. If the kids with the nicknames though Charlie was fast in the ring, they should have seen him hit the dance floor in Studio 54. He was spending money faster than he was making it but the wins kept coming and the show went on.

By the summer of 1984, Brown had a superb record of 23 – 0 with 17 wins by way of knock out. But the lifestyle was taking its toll and the wins were coming by the scenic route. Within the past year, he had gone the distance on four occasions with one of those wins on points and another by a majority decision. It was time to secure a title shot before Charlie had time to party his way out of contention. That title tilt would come against Harry Arroyo for his IBF World Lightweight belt. Arroyo had successfully defended the title against another Charlie Brown, this time “Choo Choo”, in his last outing and he had shattered the dreams of “Rockin” Robin Blake three months before that. This would be a huge ask of the young Illinois man who would still only be 21yrs old on the night of the fight.

Brown threw everything he had at Arroyo and, most ringsiders felt that he won the first 5 rounds. He was dogged and filled with the confidence of youth. Never having tasted defeat and having enjoyed the adulation of his, mostly, female fans, Charlie may have felt that the older Arroyo was there for the taking but “life makes fools of us all” as they say, and a stiff jab and clean combinations from the champion would expose Brown badly in round 6. The trend would follow in round 7 with Arroyo simply dismantling Brown and it was a testament to the young man’s spirit that he stayed on his feet. But the end was nigh and the champion went for the kill from the bell on round 8. Referee Larry Hazzard stepped in superbly within a minute and saved Charlie any real punishment. Brown pocketed $65,000 for the fight but matters outside of the ring would unravel in a mirror image his last 7 minutes with Arroyo.

Charlie was now 23-1and he had acquitted himself well against a good champion. One would imagine, the future was bright for young “White Lightning” but the lonely figure on “The Boulevard of Broken Dreams” was never too far and he stepped into the light on Charlie’s next outing. To re-establish himself as a top contender, Brown would fight the lightly regarded Harold Brazier in Nevada. The fight was a disaster from the start and Brown was knocked out in round 8. He picked up a check for $5,000 and parted company with Don Turner and Lenny Shaw. He would, instead, sign with the late Dan Goossen on the hope of getting his career back on track. “One of the first things I told him was no booze” Goossen said “One beer and you’re outta here. That was our deal. He said he had goals. We said if he came out here and worked his butt off, he’d attain those goals”. But the novelty of the new camp was short lived. Following a winning streak of just three fights, things began to really crumble around Brown and the losses came often and they came hard.

He would fight on but his career was over long before he ever walked away from the game. Of his last 14 bouts, he won only 5 and took several awful beatings. “It really hit me how far I had fallen” Brown once said “It was time for me to look in the mirror and I didn’t like what I saw. I remember talking to my mom. My eyes and face was all beaten up and swollen. She said to me ‘Charlie, if boxing is going to make you look like that; maybe it’s time to get out of boxing’. She was someone who loved me so I agreed”. He retired in 1995 having been knocked out in less than 2 rounds by Ralph Jones. The wild years had taken a terrible toll on Charlie Brown and he would forever look back with regret. “I used to go out about three times a week and party until 2 or 3 in the morning. When I was training, I’d only go out on a Friday and Saturday night but, when I was off, I’d go out every night. I was destroying my body by drinking”.

I read a report in 2008 that Charlie had drifted for many years before returning back to Moline and working the river boats. It went on to say that he had family there and he was a grandfather. A calm, indeed, after the storm that saw “White Lightning” strike at the very pillars of boxing in the early 80’s.