Jack Blackburn: Prizefighter, Trainer of Joe Louis, Scourge to Jack Johnson

There was no love lost between Jack Blackburn and Jack Johnson. Fresh off an engagement at Hubert’s Dime Museum-a seedy, self-contained freak show in Times Square boasting bearded ladies, sword swallowers, dwarves, wax dummies, witch doctors, a flea circus, and the former heavyweight champion of the world-Johnson drove to New Jersey to drop in on Joe Louis’ Pompton Lakes training camp where “The Brown Bomber” was in preparation for his 1935 Yankee Stadium showdown against “The Ambling Alp” Primo Carnera. There was an odd connection between Johnson and Louis.

There was no love lost between Jack Blackburn and Jack Johnson. Fresh off an engagement at Hubert’s Dime Museum-a seedy, self-contained freak show in Times Square boasting bearded ladies, sword swallowers, dwarves, wax dummies, witch doctors, a flea circus, and the former heavyweight champion of the world-Johnson drove to New Jersey to drop in on Joe Louis’ Pompton Lakes training camp where “The Brown Bomber” was in preparation for his 1935 Yankee Stadium showdown against “The Ambling Alp” Primo Carnera. There was an odd connection between Johnson and Louis.

Jack, after chasing Tommy Burns across the globe and finally cornering him in Australia on December 26, 1908 (Boxing Day, appropriately) to become the first black heavyweight world title holder, faced myriad misrepresentations and derogatory characterizations in the press, as he and other African American fighters had for decades prior, of course. Uncaringly caricatured in newspapers as a watermelon-eating halfwit or barely evolved savage, Johnson’s championship reign also inaugurated the search for The Great White Hope.<!–more–/>

Reporting for the New York Herald, Jack London-novelist, socialist, and white supremacist-pleaded with retired former champion Jim Jeffries to extricate himself from his alfalfa farm in Burbank, California to remove the “golden smile” from the face of Johnson, to whom he referred as a “playful Ethiopian”. Ironically, Johnson would add to his dubious show business résumé the thankfully non-singing role of a captured Ethiopian general in a production of Verdi’s opera Aida staged at the New York Hippodrome in October 1936.

Because Primo Carnera, the 6-foot-9 man mountain also known as “The Gorgonzola Tower”, hailed from Fascist Italy and Benito Mussolini was further encroaching upon Ethiopian territory in brazen violation of the two nations’ 1928 peace treaty, Joe Louis found himself cast as the hero to Carnera’s antagonist, representing the beleaguered African nation. Capitalizing on the role thrust upon him, one of the souvenirs made available to visitors of Louis’ camp were custom made “Brown Bomber” Ethiopian flags. It seemed to be of no more than secondary relevance that Louis was born in Alabama and fought out of Detroit or that Johnson, the third of nine children-and first son-born to former slaves Henry and Tina Johnson came from Galveston, Texas and not from the African continent, Ethiopia or elsewhere. From the late 18th to mid-20th Centuries, “Ethiopian” served as a sort of catch-all racial identifier for a certain portion of America’s disenfranchised blacks.

Jack Blackburn was hardly concerned with genealogical or geographical origins. What weighed on Blackburn’s worried mind was the fact that the opportunistic Johnson was sniffing around Pompton Lakes with the intention of insinuating himself into Louis’ inner circle, thereby muscling “Chappie” (Louis’ nickname for Blackburn, a playfully reciprocal one first used by Jack toward Joe and just stuck) out of the picture.

The bad blood between Blackburn and Johnson was first spilled in 1908. Johnson had issued an open challenge for a sparring session in a Philadelphia gym, an offer that Blackburn had taken the soon-to-be champion up on, leaving a crimson stream pouring from Johnson’s nose and tarnishing that “golden smile” so reviled by the author of White Fang and Call of the Wild. On December 30th, four days after Johnson’s victory over Tommy Burns, the poker game Blackburn played with his older brother Fred, who had insulted Jack’s white common-law wife Maud Pillian, had devolved into a heated altercation. Fred slashed Jack’s face with a knife, resulting in the jagged semi-circular scar raising the flesh from beside his left eye to just below the bottom lip. Only two weeks later, the intervention of Blackburn and his friend Alonzo Polk only threw fuel onto the fire of an argument between Maud and Polk’s wife Matilda.

Jack shot Polk to death, once each in the neck and stomach, and reportedly struck Matilda in the back as she attempted to flee the scene, though she survived. Maud also caught an errant bullet during the pandemonium. Some accounts erroneously attribute a triple murder to Blackburn, suggesting a tangled web of lustful deceit which may or may not have been the case. What is certain is that, having been sentenced to 15 years for manslaughter, Blackburn appealed to Booker T. Washington, Sam Langford, and new world champion Jack Johnson for legal assistance and moral support. While Langford and Washington did what they could, Johnson-still mindful of the embarrassing beating suffered at Blackburn’s hands-is said to have replied, “Let the sonofabitch stay in jail.”

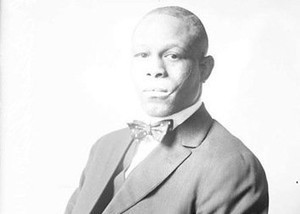

The son of a preacher man, Jack Blackburn was born in Versailles, Kentucky on May 3, 1881 under the Christian name Charles Henry. Urged by his father toward a ministerial vocation, young Charles preferred the baseball diamond and the boxing ring to the pulpit and pews. Even long after moving to Indianapolis to pursue prizefighting as “Kid Blackburn”, he would find time whenever possible to teach Sunday school. He was described by Nat Fleischer in the fifth and final volume of his collection Black Dynamite as “modest, unassuming, soft spoken, but could fight like a demon when aroused.”

Though his weight fluctuation (normally between 132-140) offered only minimal wiggle room between lightweight and welterweight, Blackburn was often thrown in against opposition of a decidedly heavier variety. He made his debut by knocking out Al Bean in the seventh round on April 29, 1900 at the Athletic Club of Alexandria, Indiana in what appears to have been Bean’s sole venture into the boxing realm. Whether it was the extreme brand of punishment dealt out by Blackburn that accounted for Bean’s abrupt and permanent departure from the prize ring is not known, but may be a good guess. A second-round knockout of Billy Love in Blackburn’s fourth fight (earning him $7.50) caught the attention of Dick Kain, a writer for the Philadelphia Record who introduced Jack to Manhattan Club owner Burt Crowhurst who procured stiffer competition and bigger purses for “Kid Blackburn”. He would take home $100 for each defeat of newcomer Bob Fanning, two points wins occurring one week apart. Blackburn once told Joe Louis how he would often wear boots two sizes too big in the ring so that he had a convenient hiding place for purse money, sometimes paid out in gold coins, which he would always demand in advance from untrustworthy promoters.

From there, a change of scenery was the order of the day for the rechristened “Philadelphia Comet” in 1903. Blackburn fought two different men on September 25th at the State A.C. Having accidentally hit his scheduled opponent Tommy Cleary with a low blow, rendering him unable to continue past the first round (officially recorded as a no-contest), the unfortunate Tommy Daly would be thrown in as a replacement and knocked out in the third round for his trouble.

Undefeated in 29 fights, Jack was matched against the great Joe Gans, whose world lightweight title was not at stake, on November 2nd. Blackburn rocketed off the canvas so fast following a first-round knockdown that the referee did not have time to initiate a count and peppered “The Old Master” with a series of right crosses. Seven consecutive jabs just prior to the bell at the end of the sixth and final round reportedly sent Gans’ head spinning this way and that. The champion was awarded the newspaper decision by his hometown Baltimore Sun but the Philadelphia Record, Philadelphia Inquirer, New York Evening World, New York Sun, and Baltimore Morning Herald all scored the outcome in Blackburn’s favor. “He’s the only man I’m afraid of,” Gans said afterwards. “I don’t think there’s anybody in the lightweight class that I can’t whip, but I hate to tackle Blackburn.” Fear-struck or not, Gans would twice again tackle Blackburn, claiming a 15-round points win on March 25, 1904 in Baltimore and handing Jack a 6-round drubbing back in Philadelphia on June 29, 1906 to walk away with the unanimous newspaper decision.

Seven weeks after his initial meeting with Joe Gans (with his first defeat coming in between, a six-round points loss to Dave Holly), Blackburn was paired off at Boston’s Central Athletic Club against another legend in his own time, Sam Langford, for the first of six fights. Despite eyewitness accounts substantiating Jack’s dominance, the bout was declared a draw as the result of a pre-determined clause whereby a fighter would emerge the victor only by way of a stoppage inside the 12 round distance. Their “light-hitting affair” in Philadelphia two weeks later also resulted in a stalemate, as would the next return engagement at Massachusetts’ Marlborough Theatre.

“He just kept coming in and lambasting me and ruining my complexion, and punching my stomach up in my chest and everything like that,” Langford told the Winnipeg Tribune about that brutal 15-rounder. “He once hit me so hard that I got him in a clinch and felt his gloves trying to find a horseshoe. He hit me another time and for a minute I saw 18 Blackburns flying around in the ring and leaping at me. After I got back to my corner from that round, Joe Woodman (Langford’s manager) says to me, ‘Better quit playing now, Sam, and finish him.’ ‘Listen, Joe,’ I said, ‘If you see that boy hit me again like he did In that round, just drop everything you are doing and get me an undertaker.’ Jack never hit me any more such blows, that’s why I’m alive to tell about the fight.” Langford did indeed live to fight another day and another three more times within two months against Blackburn in 1905, a points win beneath a revival tent in Leiperville, PA followed by yet another draw and finally a no-contest in Allentown when, as alleged by an article in the Philadelphia Item, the fight was pre-emptively discovered to have been a fix.

Jack three times fought-and three times was the beneficiary of newspaper decisions over-“Iron Man” Joe Grim and defeated rugged George Gunther, born in Australia and fighting out of Boston, seven out of ten bouts with the other three being draws. Blackburn was floored in the first and last stanzas en route to a six-round decision loss to Philadelphia Jack O’Brien on June 10, 1908 but would finish off the year with a ten-fight unbeaten streak which would be discontinued by his murder of Alonzo Polk and four years, eight months served of a 15-year sentence. “He never sought trouble,” Nat Fleischer followed through on his earlier assessment of Blackburn, “but when once it came, he was in the thick of it. At times he lost his bearings through drink and when that happened he was a devil in disguise.”

A sensational and, it goes without saying, spurious headline in the February 1, 1909 edition of the Chicago Tribune screamed “Jack Blackburn A Suicide? Colored Fighter Said to Have Poisoned Himself in Prison.” The story the paper ran with supposed that Blackburn, while awaiting trial at Moyamensing Prison, ingested a vial of poison smuggled into his possession by a female visitor. Prison physician B.F. Butcher refused to confirm or deny the rumor and other officials remained silent on the matter with the exception of Inspector General St. Clair Mulholland who “says the report is untrue”. Which it was, of course.

Jack would mount a comeback on April 4, 1914 with a six-round win over Tommy Howell but bit off more than he could chew with heavyweight Ed “Gunboat” Smith who had given Jack Johnson a working over in a sparring session leading up to Papa Jack’s 1909 showdown with Stanley Ketchel, setting off an eleven fight winless streak for Blackburn. One of those defeats-at Duquesne Gardens in Pittsburgh on January 25, 1915-came against Harry Greb who manhandled Blackburn over six rounds with a relentless attack that could not be neutralized by body blows or tricky counter punches. Jack soldiered forward, valiantly but less and less frequently, until 1923 when he retired with an official ring record of 46-9-12 with 33 KOs which does not take into consideration newspaper decisions nor bouts exhibited in states where prizefighting was still illegal. All things considered, Blackburn once surmised that he had participated in 385 fights and the likes of George “Elbows” McFadden, Frank Klaus, Billy Papke, Battling Nelson, and Stanley Ketchel are all said to have gone well out of their way to avoid fistic confrontations with him. And though he never did square off against his once and future nemesis Jack Johnson, with the exception of that one infamous sparring session, Blackburn did come out on top of an eight-round decision on December 20, 1920 against a light-heavyweight from Boston named Jim Green who fought under the alias “Young Jack Johnson”.

Having taught boxing to youths as a means of self-defense both before and after prison, Jack would go on to train future world lightweight champion Sammy Mendell and bantamweight title-holder Bud Taylor. Having witnessed and experienced firsthand the way both the boxing community and the world at large chewed black men up and spit them out into the margins of society, Blackburn had to be won over by numbers-runners John Roxborough and Julian Black in accepting their initial $35 a week offer to take the youngster from Detroit named Joe Louis on as a pupil. It didn’t take long for Jack to go from being a tough-nut skeptic to being well-loved “Chappie”. Jack Johnson may have been keeping company with wax figures at Hubert’s Dime Museum but he was certainly no dummy. He had to be aware that he was specifically referenced by Louis’ troika of Blackburn, Roxborough, and Black as an example of how Joe ought not to conduct himself in order to appease the general public while navigating his way to the heavyweight championship last held by Papa Jack. Never was Joe to be seen or photographed in the company of a white woman or gloating over a fallen opponent either in the ring or in the media.

That being said, Blackburn felt it necessary to instruct Joe to “get some blood in my eyes”, as Louis recalled. “When you get in that ring, you go for the kill,” Chappie elaborated. “Negro fighters do not go to town winning decisions. Let your right fist be the referee.” Killer instinct would carry you only so far if not guided by proper technique. With Blackburn holding the heavy bag in place while Joe went to work “morning, noon, and night till I could have sworn the bag was punching me too”, Louis was transformed from an awkward, off-balance swinger into an honest to goodness puncher, with feet firmly planted to allow maximal utilization of a stable center of gravity. “He said people going to fights don’t want to see a dancer or a clincher, they want to see a man who goes for the guts.”

When Roxborough sent Johnson on his way back to Times Square from Pompton Lakes in 1935, despite Louis’ open declaration of what a thrill it had been for him to meet the champ, Jack publicly supported Carnera and would do likewise with Louis’ subsequent opponents Max Baer, Max Schmeling, and Jack Sharkey. Johnson would resurface twice at Joe’s training camp prior to the Baer fight, Louis refusing a Life magazine photographer’s request to snap a shot of the former and future heavyweight kings together, or even to enter the ring to spar until “that black cat” left the premises. Having bet on Schmeling prior to the German’s first bout against Louis in 1936, Johnson won a handsome sum of money which he counted and flaunted on his walk back uptown and had to be rescued by police from an unruly mob. Johnson would offer to work the corner of heavyweight champion James J. Braddock for his defense against Louis, an overture which was declined the same as Johnson’s challenge to face Louis in a three-round fight three months before Joe would turn the hands of the clock forward to midnight on the “Cinderella Man”. He had worn out his welcome and it was obvious to everyone that the market value on that golden smile of Johnson’s had plummeted to a bargain-basement low. Until it rebounded in the radicalized 1960s when Muhammad Ali embraced Jack Johnson’s flamboyant mystique while branding Joe Louis an antiquated “Uncle Tom”.

One month removed from Louis’ September 24, 1935 fourth-round knockout of Max Baer at Yankee Stadium, Blackburn was involved in yet another antagonistic conflict ending in gunplay. Fifty-two year old Jack, who was characterized as “a violent man with a terrible temper who always carried a piece” and “kept even the most hardened fighters in fear” in Joseph Bourelly’s essay for the book The First Black Boxing Champions, became embroiled in a back-alley brawl with a man twenty-eight years his junior named John Bowman before matters escalated into a shoot-out on opposite sides of a Chicago street. Two bystanders, a little girl of nine by the name of Lucy Cannon and sixty-nine year-old Enoch Houser, were caught in the crossfire and both critically wounded. In spite of the fact that Houser later died from his injuries, and his prior manslaughter conviction notwithstanding, Blackburn was eventually acquitted in this case after posting a $10,000 bond pending trial, as well as much confusion and speculation surrounding the police investigation and judicial process.

The Buddy Baer fight would be the last one for which Joe would have Chappie wrap his hands, once nimble fingers now gnarled and arthritic, and stand in his corner on legs no longer sure of themselves. After volunteering for the Army, the last time Louis would see Jack would be during a five day furlough in Chicago where they discussed Joe’s victory over Abe Simon which Blackburn had to listen to on the radio from a hospital bed, laid low with pneumonia. Upon his return to Long Island’s Camp Upton, Louis received a telegram informing him of Chappie’s death on April 24, 1942.

Though there is no denying his menacing reputation, it is very obvious that Joe Louis, who had named his firstborn daughter Jacqueline (or Jackie, a nice melding of Jack and Chappie) as a living tribute to Blackburn, was provided the rare opportunity to know and love a version of Jack Blackburn few others were allowed to even get a glimpse of. “I guess I thought I’d be heavyweight champion forever and Chappie would be always with me,” Louis lamented in his memoirs. “Chappie had been another father, a teacher, and a friend. So, when you really think about it, I lost three people, not one.”