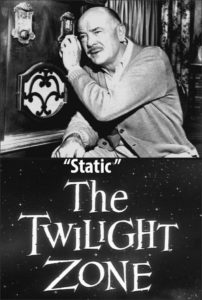

The Twilight Zone Review: Static

I outrightly reject the narrow-minded cliché of the episode “Static” that purports radio to be some sort of superior story-telling entertainment because of what it lacks, the visual element. And believe me, I understand the magical feeling of lying in the dark with family while listening to Sir Ralph Richardson recite “A Christmas Carol” by Charles Dickens. Some critics in writing about “Static” praise the episode for this very byzantine notion, thinking radio works on our imagination more than television does, or I assume also movies. And actually now that I mention it, why is it that we only hear people spout that cliché when comparing radio to TV. They shrink back cowardly from applying the same comparison to movies, and why is that? Aren’t movies also “guilty” of supplying a visual image as well, thereby supposedly squashing imagination?

I think they avoid the similar comparison because motion pictures have in the 20th century come to climb a pinnacle of cultural entertainment when we start delving into the classics and how their magic has surpassed even the pleasures radio offered. But because of television’s comparable physical size to radio, critics think they can get away with it. But in so doing they are making the very mistake that they accuse television of perpetrating—they are forgetting that the whole point of it all is storytelling. And storytelling can be as magical and imaginative coming from a TV screen as it can from a radio. The imagination is not supplanted just because TV serves up an image. Because imagination still reaches out and beyond whether we watch and image with sound or just listen to the sound of a radio. Our imagination works feverishly all the time, even when watching a TV program; what is more emotional and stirring then seeing a close-up of the face of a performer giving a marvelous performance and thinking about the dialogue they are saying and the ides and thoughts behind that face? I suspect many “Twilight Zone” viewers weren’t fooled by this antiquated notion that springs more from a longing for youth than a thoughtfully examined study of the storytelling process. And that’s why “Static” received only 6 votes in my survey of fans and writers asking, ‘What is your favorite episode of the original Twilight Zone series?’ tying it with 11 other episodes for 106th thru 116th place of the 156 episodes.”

This was one of the infamous 6 episodes to be filmed in a Season 2 decision to cut costs by videotaping a few of the episodes. The result was “disastrous” according to Rod Serling, however, on so many lists of critics’ choices of the top episodes, two of those six are routinely ranked in the top 25 or so: “Twenty Two” and “Night of the Meek.” It is undeniable though that the episodes look terrible compared to the filmed TZ episodes. I will say this about “Static” though—it might be the best-looking of the 6 videotaped episodes. Perhaps because it was the 5th to be videotaped, so they learned a bit more technique. What rarely gets mentioned is the poor sound quality that also went hand in hand with filming in the style of a live audience, and no where was that more evident than in “The Lateness of the Hour.” But in “Static” the crew also managed to work things out so the audio doesn’t suffer so much.

The episode opens with a group of middle-aged (or so) boarders at a rooming house watching a TV western. They’re all engrossed, except for our lead, Ed Lindsay, played by Dean Jagger. What’s obvious to me, is he is a terrific actor, but is handcuffed here by the writing as an overtly cranky old man, so cantankerous that it becomes too difficult to find much sympathy for this curmudgeon whose negativity too often crosses the line into cruelty. I don’t mind his diatribe in this opening scene as he gets up and ridicules everyone for letting their brains turn to mush, as they glue their attention to the TV, but I do find it unnecessarily awful when he takes so many jabs at the very sweet woman Vinnie who is also a boarder and as it turns out, used to be his fiancée. The writers could have done a better job at making his frustrations turned more inward instead of so fiercely turned outward onto other people, especially those who’ve done nothing to deserve it. And they never do really adequately explain the psychology behind his crotchetiness despite having Vinnie (Carmen Mathews) deliver a monologue later that attempts to do so.

So after making fun of the TV show’s commercials and stupid ads, he marches off. Didn’t radio also have its share of ridiculous commercials too if I’m not mistaken? But Mr. Lindsay goes down into the basement and digs out an old radio that he had stored there and hauls it upstairs with the help of a little boy who peered in on him from the street through the window. When he gets up from the basement, he is joined by the Professor (Robert Emhardt) and Vinnie, both of whom have a cheerful curiosity. But when Vinnie sweetly comments, “I remember that. I thought you’d thrown it out years ago”, Ed shoots her this arrow: “I never throw anything away that’s worth keeping.” Ouch. The writing just has no sense of what’s too much. And they provide no reasonable motivation for his level of meanness.

And why for that matter did he have his radio stored down there for so long, within easy retrieval but never doing anything about it? It’s been down there for decades apparently. So why all of a sudden is he bringing it upstairs? What was the catalyst? Surely his opinion of television has been harbored for a long, long time, it didn’t just suddenly pop up today. And it was RIGHT THERE in his basement—it’s not like it was in some storage facility in another state!

Once he has it in his room he plays with the tuner and gets a signal. It’s Tommy Dorsey and his orchestra playing “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” and the effect of it clearly soothes this savage beast. He lies down, as transfixed by the song as he accused the others of being when they watched TV—the “one man’s ceiling” lesson obviously lost upon him.

He listens to more old radio shows as they rise up from their graves, shows like Major Bowe’s Amateur Hour, and Fred Allen (including the character that inspired the Warner Bros. Looney Toons animated rooster Foghorn Leghorn!). When the static interferes, he tweaks with it and we hear that the station is WPDA in Cedarburg, New Jersey.

Vinnie comes knocking at the door to tell him that dinner is ready downstairs, and all he can do is use this as another excuse to unleash an embittered attack about how ever since he can remember, “women have been running his life” do this, do that, etc. but Vinnie cuts him off not letting him continue spewing, and we hear her snap back for the only time: “Mr. Lindsay I don’t care if you starve to death. I just want to make sure that it’s on purpose and not because you’ve forgotten that food is available.” It’s an exchange that will take on very significant meaning later when we listen to Vinnie’s rundown for Ed on what she thinks is going on inside his head, and what happened to them that broke up their relationship.

At the dinner table, Lindsay and all the boarders talk about Tommy Dorsey on the radio, and one of the younger boarders, Mr. Bragg argues that Ed couldn’t have heard Tommy Dorsey because he was dead. I found this puzzling, that someone wouldn’t understand the nature of recordings and how they can be played on the radio all these years later. It doesn’t seem likely at all that someone didn’t understand that.

But Lindsay invites them (challenges them?) to come up to his room and listen for themselves. The head of the boarding house, Mrs. Nielsen tells Vinnie, “Mrs. Broun you can thank your lucky stars that you never married that man!” And Vinnie bows her head in sorrow. That’s not quite the first clue we hear how close the two were. When Ed first went into the basement to dust off the old radio, he picked up a framed photograph of him and Vinnie posing tenderly together. He looked fondly at it for less than one second, before setting it aside.

Vinnie and the Professor go on up to hear his radio, and wouldn’t you know it, he can’t find anything but static. They try calling the station to find out if there is a “transmitting problem” but they find out that WPDA has been out of business for 13 years. Vinnie reports that she can’t find it in the newspaper listing. Ed asks the Professor “Then what did I hear?” but the Professor is stumped. Vinnie makes an attempt to talk with Ed, but he’s lost, trying to find the station. Vinnie follows out after the Professor to ask about Ed’s state of mind. With those two out of the room, the radio does indeed come back on with the voice of FDR.

When Ed excitedly runs down to them in the living room announcing he’s got it again, they dutifully go up, but once again, the radio only offers static. Sheepishly, Ed apologizes. He tells them it was “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” again and we cut to a meaningful close-up of Vinnie which we’ll understand more about later.

And now comes the big scene in which Vinnie tries to reach inside of Ed’s heart and mind. At first he protests that they all must think he’s crazy, but she convinces him to sit and listen. She tells him that right now he’s one of the sourest most cantankerous men around to which he responds sarcastically, “Thanks!” but she softens that as she adds, “And I’m not much better. We’ve been living like two hermits under the same roof for the last twenty years.” I’m not sure whether to think she actually believes she’s been as sour as he has or not. It’s absolutely not true to begin with—there’s no evidence of that in the slightest from what we see. But perhaps she only said that as a diplomatic peace offering. “Twenty long years wondering what went wrong” she continues. He protests again, but she insists he knows exactly what she’s talking about. Hopefully we will too soon. She tells him (and us) “We were going to be married.”

He gets uncomfortable but she assures him she’s not trying to change anything. She reminisces melancholically how he proposed but before they could set the date, his mother fell ill, and he decided to delay getting married—to wait while he took care of his mother. So they waited and waited. And then she says, “And we waited until by the time your mother died, it was too late.” He’s about to protest again, which I feel was a lazy ploy by the writing to interrupt that trail, so they didn’t have to delve into what happened that made things too late. She doesn’t seem like the kind of woman who would let things drift apart—I see instead her being the type of character that would help Ed with the situation he was in. There’s no convincing explanation for how things devolved. She continues talking and goes down a path I again found difficult to swallow: “Oh I know you don’t care anything about me now. I’m just a silly woman who watches TV, dyes her hair, grows old. You don’t even like me anymore. And I don’t blame you. You’re a bachelor set in your ways. You can’t change what you are. And neither can I. We had our chance and missed it Ed. But I’ll tell you one thing that’s true. And I know its true. You did love me, as much as a man ever loved a woman.” And after a pause, Ed concedes this point. It all makes for a somewhat moving monologue but darn it, I just wish there was some more honest deep probing as to why things really broke apart because to me it just seems like it should have mended a long time ago. I don’t believe that it couldn’t, especially with the two of them thrust upon each other living under the same roof all these years.

Finally Vinnie does somewhat touch upon something deeper: “And now you love what we were. What we might have become together. So just about this time every year, it would’ve been our anniversary (Hey, I thought she said she wanted to set a date but they couldn’t!) you start getting unhappy. You want to go back to 1940 and start over again. Why do you think you keep hearing ‘Getting Sentimental Over You” on the radio?” And now the reveal: “That was our song Ed.”

Apparently this loving couple had a close relationship with the radio way back when, as they would huddle together and listen to all those programs that Ed has been saying were popping up on his radio now. She tells him how when he hears those programs now he’s like a young man again with his whole life ahead of him. “But it isn’t so Ed. It’s all over between us. We missed our chance. We can’t go back.”

But instead of Ed trying to be constructive he seizes this opportunity to accuse her of thinking he’s going dotty. She tries to counter that, but he doesn’t let her, almost as though facing the truth she was speaking of was more painful then opting for the anger to feel at being thought of as getting soft in the head. He kicks her out of the room, and retreats back to his radio and listens in.

The next day he comes jauntily into the boarding house carrying groceries, and cheerfully drops them off into the kitchen. He turns down the Professor’s offer to play checkers as he recites the line-up of radio programs that await him up in his room. But when he enters his room he sees that the radio is gone. They took his radio to the junk dealer. Vinnie says, “We were only trying to…” but Ed cuts her off, “The junk dealer!? You gave my radio to the junk dealer?!”

The writers conveniently had him cut her off because I can’t think of the rest of what Vinnie’s sentence would be: “We were only trying to”…what? I’ll take a stab at guessing they figured if they got rid of his radio he’d be forced to pay attention to them? To rejoin the social dynamics of the whole house of people. But honestly who would have the gumption, the cruelty to do such a thing? It’s just one more thing I can’t buy.

But he goes and has to buy back his radio from the dealer. Back in his room he gets some static but then is able to conjure up that song of his and Vinnie’s from so long ago. We hold on a close-up of the radio as he calls to Vinnie, who comes excitedly into his room—except that she’s much younger now. Well, as much as a wig and make-up can do. And when we cut back to Ed, he too is younger with a full head of hair and make-up as well. The two embrace, as we glide over to the radio and Rod Serling’s narration kicks in. He seems to hold a more positive view of this ending: “Around and around she goes, and where she stops, nobody knows. All Ed Lindsay knows is that he desperately wanted a second chance, and he finally got it – through a strange and wonderful time machine called a radio.” That’s nice I suppose, but it kind of feels as though the more likely interpretation is that Ed has retreated full tilt into imagining a past, that isn’t really there.

Don’t give me any static about this, but I rate the episode a 4.4 here on WTTZ.

[si-contact-form form=’2′]