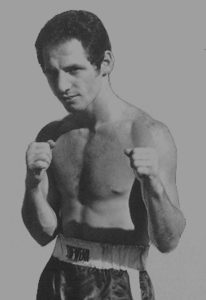

Ringside Report Looks Back at Tough Former World Title Challenger Johnny Lira (1951- 2012)

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

“Our father, Johnny Lira, was more than a boxer.”

I cannot think of a more fitting way to start any column but by way of a tribute that came from a daughter. It is even more poignant given that Gina Lira’s words are echoed by the reality of her father’s life.

You get used, when you delve into the archives, to read about the careers of long forgotten pugilists that went way beyond their active involvement between the four corners of a ring. For some it is all about the influence they have whilst they box, for others it come afterwards when they use their noticeable profile for good.

For Johnny Lira, 29-6-1, 15 KO’s, it was just exactly that. Nicknamed the “World Class Pug” this Chicago native who was born in the city and died there, was an active boxer at all levels. Born to Duiko Lira and Delores DeRose Lira in 1951 Johnny was a mischievous red-headed and freckle-faced troublemaker – he could have passed as Scottish – whilst being the youngest sibling of two other children. According to his family that mischievous outlook on life continued well into his adulthood. Having come from an area where a fight meant a multiplicity of things, his amateur career began at the Chicago Youth Organization under Harry Wilson and Chuck Bodak. He won the Chicago Golden Gloves in 1974 and 1975 as a welterweight and middleweight, won a Catholic Youth Organization title. He then went professional after relocating to Las Vegas, training under Johnny Tocco and winning the USBA belt in 1978 and attempting to take a world crown in 1979.

Of his background, Lira was once interviewed in a documentary by Terry Spencer Hesser and spoke of his going from boyhood mischief maker to ring legend. “I had compiled a long arrest record from the time I was 8 or 9 years old, up until the time I was 19,” Lira said. “And the many judges I stood before had wanted to wash their hands with my life and they seen that I was gonna be going nowhere, and they were getting ready to lock me up and throw away the key. One (criminal court) judge, Marvin Aspen, took a chance. He said if I kept my life clean, he’d have a surprise for me.

He turned the sentencing around and maintained as long I stood into boxing and kept discipline and lived a clean lifestyle and continued to win my fights, he’d put me on a work release program. … I became the middleweight champion of the Golden Gloves in that year. I am a true testimony of what boxing can do as far as … taking a young man’s negative energy and turning it to a positive direction. I should either have been dead, in the penitentiary, or both. But here I am talking to you.”

His first professional fight was on the 17th of November 1976, in Las Vegas against Genaro Gloria. He won that debut by stopping Gloria in the 4th round of 4 rounds.

His first professional title came in 1978 when he beat Andrew Ganigan by knockout in Honolulu on the 1st of August for the USBA lightweight crown; he knocked Ganigan out in the 6th round.

Then came his big chance in 1979 when he fought champion Ernesto Espana for the WBA belt at lightweight in his home town of Chicago, in the Conrad Hilton. He got stopped in the 9th round. It was his first defeat in the professional ranks.

He found himself back in the ring for a USBA title, his time at super lightweight on the 18th of August, 1981 back in Honolulu. He was the one stopped this time – in the 9th round.

Active professionally for such a short time, from 1976 until 1984, when he retired after losing in Arlington Heights against Russell Mitchell on points on the 22nd of September 1984, he had just one tilt at a world title but his greatest fight came after he left the sport. As a man who swore that anything was achievable, that everyone has the potential to succeed, he was the man to whom you could never say never Johnny Lira found himself in receipt of a lifesaving liver transplant which gave him a new opportunity to inspire. And inspire he did. He went on to teach amateur boxing at the Union League Boxing Club, became a referee and a judge and never seemed to tire of turning up to provide local support to local boxing cards.

But it did not end there.

He was an activist. He worked diligently on behalf of boxers and founded the Sports Professionals and Amateurs Resolving To Achieve (SPARTA). In trying to get people to come around and see how badly they needed a pension and union, and how ridiculous it was that they didn’t already have one, Lira was perhaps ahead of his time. Or boxing was very much behind those times…

He was also an actor appearing in “Gladiator” with Cuba Gooding Jr. and the History Channel’s “Who Shot Martin Luther King, Jr. And then on the 8th of December 2012 he was to lose his life due to CTE – Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy which is a degenerative brain disease found in athletes, military veterans, and others with a history of repetitive brain trauma – hardly surprising for a boxer. He was only 61 years of age. He donated his brain for future study, and it went to Boston university and if there is a giver, a grateful giver this is the man to admire.

I began with the words of his daughter and let me end with them too. In her own obituary of a much loved figure she wrote, “Our father had a very close relationship the Union League Boys Club (club #2) throughout his whole life, a youth club member, staff member, volunteer, mentor, and in the late 1970s he was the head boxing coach. … He loved kids and believed so firmly that children, especially ones with few options or many disadvantages, should be given an outlet, something that teaches them hard work and discipline while boosting self esteem and pride. That was why he believed boxing was a great tool for kids.”

[si-contact-form form=’2′]