Ringside Report Looks Back at Kenyan Boxer Philip Wariunge

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

The United Kingdom gave the world an Empire for which we are rightly, being examined. I sit in the shadow of a city built on the backs of slavery and tobacco. It was a main line between Africa and Jamaica where our streets celebrate the past in place names which are based on the slave owners and plantations, over which we hang our heads in shame.

It is however, one side of the legacy. When it fell apart the Empire provided the Commonwealth of nations. A group of countries once ruled by us who are now independent of us but to whom they see an allegiance, a benefit of association. We should not be fooled into thinking that this should make us feel all fuzzy and warm about our past, nor that former colonies should be uncritically welcomed to the fold. It includes such difficult countries to love as Zimbabwe and Kenya.

In a sporting sense it does bring a wealth of opportunity to gaze at people we would not normally know, ordinarily be aware of or celebrate as we ought. In a sporting sense that happens through the Commonwealth Games. Like the Olympics, the Commonwealth Games are on a 4 yearly cycle, and this gives us an optimum opportunity to see what the diaspora has and welcome it in. For the duration of the Games, we may be rooting for our guy, but sometimes, when we have no champions of our own, we can vicariously have pleasure in supporting someone who we knew before anyone else did, after the Games have finished.

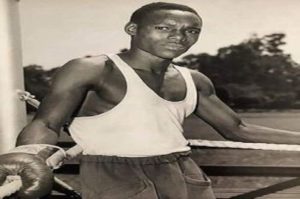

Like Philip Wariunge, 14-10-1 KOs.

A Kenyan super bantamweight boxer who still lives in his own country he shone in three Olympics including one in which was not without its own controversy. Active professionally between the years of 1973 and 1978, he never made it to the top as a champion, though he did fight for two world titles in one year, but he also left a legacy, an imprint on the sport.

Depending on who you read, Wariunge was found by an itinerant, touring Scot or by Irish coach Maxie McCullough in Nakuru in the 1960s. Wariunge’s version is that it as the Irishman! Wariunge came from a part of Kenya, Nakura, that provided many boxing champions and participants including nearly half of the national team that participated in the 1968 All Africa Boxing Championship in Lusaka, Zambia.

came from a part of Kenya, Nakura, that provided many boxing champions and participants including nearly half of the national team that participated in the 1968 All Africa Boxing Championship in Lusaka, Zambia.

Having been seen by McCullough at St Theresa’s Primary, and encouraged by his headteacher to try out, Wariunge was plucked from the soccer team to the road to pugilistic fame. In an interview with a Kenyan media organ, he was to reflect, “I owe it all to my all-time best coach McCullough. He taught me how to mount a tight guard, footwork and punching skills and releasing damaging hooks correctly.”

In his three Olympic Games, though he made little impact in 1964, he won bronze in Mexico City in 1968, and the Val Barker Trophy for outstanding boxer there – the very first Black African boxer to do so – before gaining the silver medal in Munich in 1972. He also won two Commonwealth Games titles in and around those Olympics – 1966, when 17 and 1970. He remains the most decorated Kenyan boxer, ever and the only one to appear at three Olympic Games.

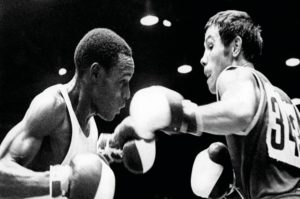

His winning of the Val Barker has not been equalled by an African boxer, never mind a Kenyan one. His international amateur journey began at the ‘64 Olympics when he was just shy of 20 years old. In 1968 his rise to prominence was halted when he faced the home boxer, Antonio Roldan, who was a scrappy competitor. At the end of the fight, it went 3-2 to the eventual winner of the gold medal, Roldan, but the boos rang out from Roldan’s hometown supporters. Wariunge was robbed.

In that interview with Nation Sport, he revealed, “I remember chaos nearly erupted on the ring side as spectators booed the judges’ decision to deny me victory. I remember coach Peter Mwarangu telling me not to greet my opponent. I defied his instructions in the spirit of sportsmanship.”

Wariunge showed sportsmanship qualities which were not evident in a response to him.

In 1972, he faced a Soviet fighter in the final, Boris Kuznetsov, and once again he was to lose 3-2.

Wariunge should have known. As he reflected many years thereafter, he remembered how, just before the bout, a Ghanaian judge came to his dressing room and told him to fight “like that was his last bout on earth. Out of the five judges, three were from communist countries. The other two were from Israel and Canada and it was therefore impossible for me to get a fair verdict.” The fight was indeed close but there are few reasons to suspect the verdict was wrong, no matter how good a tale it would be in the telling.

Like most boxers his next step was to enter the professional ring but not many would have the trials and tribulations he had. Prior to the 1972 Munich Olympics, he resigned from the Kenyan Army, but his resignation was not accepted. He explained in his interview with Nation Sport, he explained, “I wrote a resignation letter to the army headquarters in Nairobi while I was in the USA because I worked as a soldier with Kenya Army (now Kenya Defence Forces) at Lang’ata Barracks but my resignation was rejected. That is how I lost my first opportunity to turn professional. “Major Cromwell Mukungusi intervened on my behalf by talking to the then Chief of Defence Joseph Ndolo after I promised to win a medal in Munich Olympics. I won a silver medal and I was discharged from Armed Forces unconditionally. The following year I turned professional in Japan.”

His first attempt to turn professional landed him in a military prison for 42 days whilst his second was more fruitful and he turned professional in 1973. His debut was on the 27th of July 1973 in Osaka when he won on points against Kimio Shindo.

Of his entire professional career, 1976, ironically the year of yet another Olympics, saw his busiest time in the professional ring.

On the 3rd of March he faced Rigoberto Riasco in Panama City for the inaugural WBC super-bantamweight title. Knocked down in the 4th and 7th, he retired in the 8th.

Then on the 14th of June he was in Osaka to beat Futaro Tanaka on points for the Japanese super bantamweight title. He then defended it on the 2nd of September, back in Osaka when he beat Hisami Mizuno on points.

At the end of the year, on the 13th of November he had another shot at the WBC bantamweight world title when in Culiacan, he faced Carlos Zarate but was knocked out and stopped in the 4th round.

Two years later, after twenty five contests he was to retire. His final fight was in 1978 when he narrowly lost on points against Kosei Kawaguchi in Kokugikan.

Afterwards he settled in Japan, running businesses that included a bar. According to Steve Bunce in the Boxing News, in that bar were all his trophies and medals – a fair haul of them. According to Wariunge himself, his “entire savings went up in smoke.” Worse was to follow as he was deported due to not quite keeping up with his residency status. He left with his memorabilia still in the land of the Rising Sun!

He lives back in Kenya, on state aid which, given his history, is not good. He speaks of his privations thus, “I just think I’m neglected, like really neglected. This is the painful cost of being the pioneer of Kenya’s boxing. No one bothers to know where I live. Nobody treats you well. You’re viewed as a liability to the society. Nobody thinks you deserve respect and honor.”

It is bitter and whether you believe he lives in his son’s dwelling or his mothers, whether it is a hut or a house, tales of this Olympian deserves far better than recompense than that which he “enjoys” now. Bunce says it like it is in his article when he asserts, “This man is a legend, arguably one of the greatest forgotten boxers in our history. I’m not kidding. I’m serious.”