Ringside Report Remembers Former World Champion Ken Buchanan (1945-2023)

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

Ken Buchanan, 61-8, 27KOs, was the greatest boxer that Scotland ever produced, our best ever fighter. News of his death was greeted with the usual dismay but also shock that one of our own was lost to us. And with dementia finally taking Buchanan from us, we are left with such memories as this.

There are few who would ever disagree with that statement who know the game. On the cusp of managing to achieve close to what Buchanan did is Josh Taylor, who has always shown Buchanan respect and been fulsome in his admiration for a man who defined what it was to be an iconic figure of boxing. Buchanan was the man to whom he looked up and was a mentor throughout much of his career, and he spoke for us all, as Buchanan was us, our dad, big brother, weel kent cousin and the uncle you called upon when in trouble. We all loved him.

Because Ken Buchanan was flawed.

Today that tends to be vilified, but for me it adds another round of applause.

Born at the tail end of the Second World War, in 1945, the future lightweight star, the future undisputed lightweight world champion, bronze medalist as an amateur at the 1965 European Championships, 1965 Amateur Boxing Association (ABA) lightweight champion grew up in Portobello on the outskirts of Edinburgh. Young Ken found the ring at age eight thanks to his father. He remembered being taken to see The Brown Bomber at the pictures as a child, and the film about Joe Louis was so inspirational that by the end of the year in which he saw the film, he won his first title. He was eight and a half years old! His father would take his relationship to boxing keenly and Tommy, his dad, would teach from the very start of his journey not to let his guard down. His mum, Cathy, no doubt watched the emerging cultured physical specimen that was her son develop and grow into the light footed and technically gifted fighter he was to become. It is just a pity she never saw him raise his hand as world champion or the many times he was headlining at Madison Square Gardens.

On the 20th of September 1965, Buchanan turned professional at the National Sporting Club in Piccadilly, London and knocked out Brian Tonks in the 2nd round. It was an inauspicious start as he slowly began to build his domestic reputation. In fact, most of his first few fights in a professional ring did not include boxing in his home country. It was not until the 23rd of January 1967, that he appeared in the Central Hotel, Glasgow to take on John McMillan for the Scottish lightweight title – it was a triumphant homecoming as he won on points over 10 rounds.

On the 30th of October 1967, he returned to the National Sporting Club to face Jim “Spike” McCormack in a British title eliminator which he won on points.

Standing in his way of the British title, on the 19th of February 1968, in the Hilton Hotel, Mayfair, London was Maurice Cullen. Cullen was dispatched in the 11th round, making Buchanan champion and his name now seen as a worthy world title contender.

But before that there were a couple of significant life events. Firstly, whilst his father, Tommy, was to travel the world in support of his son, mum Cathy was denied the opportunity as she passed away in 1968, aged only 51. Fighter Ken, as highly respected British journalist, John Rawling wrote in the Guardian, “He claimed this spurred him on to win the world title: “I told [Eddie – his trainer] I wanted to be champion so that when I visit my mum’s grave I can show her my world championship belt.”

But before he was to get there, in 1969, Buchanan quit the sport. According to Steve Bunce, in his Big Fat Short History of British Boxing, he quotes Buchanan as saying. “I was not making enough money.” He even sent his British title belt back. What brought him back was a soothing word or several from his manager and a European title fight in Madrid and the promise he had now made to his mum.

His road to world honors, however, was not to be filled with easy marks as he took on and beat the likes of Angel Robinson Garcia and Leonard Tavarez before tasting the first of his eight defeats. It came in a European title bout where he lost over 15 rounds to Miguel Vazquez in Madrid on the 29th of January 1970. According to the quick wit of Buchanan, the referee was not in the frame of mind to give him much as he feared a riot had the Scot won. I have no idea if that made it easier to accept.

The things was, it didn’t seem to diminish his potential as a world title challenger and defended his British title successfully on the 12th of May 1970 in Wembley against Brain Hudson by knocking him out in the 5th round.

1970 was some year as he found himself in Puerto Rico in September and most in the boxing world gave him little chance against the legendary Ismael Laguna, with the fight being close to his back yard of Panama. Over 15 rounds, Buchanan won on a very tight split decision, and returned home to what you would think would be a hero’s welcome. His wife and son were at least there – the rest of the country were absent – especially the press. His legendary position in Scottish boxing was surely now to be assured, so if he was not going to get any attention by winning the damn title surely a first defense in Scotland would do the trick… or at least one in the UK.

yard of Panama. Over 15 rounds, Buchanan won on a very tight split decision, and returned home to what you would think would be a hero’s welcome. His wife and son were at least there – the rest of the country were absent – especially the press. His legendary position in Scottish boxing was surely now to be assured, so if he was not going to get any attention by winning the damn title surely a first defense in Scotland would do the trick… or at least one in the UK.

But there was a problem.

The WBA who had sanctioned the fight and the British Boxing Board of Control, (BBB of C) were, however locked in the horns of a dispute and Buchanan was denied the opportunity as the BBB of C would not allow him to defend the title in the UK.

Buchanan was wearing the WBA strap, but to be undisputed he needed the WBC belt too. And so, on the 12th of February 1971, he nipped across to Los Angeles and fought the WBC champion Ruben Navarro with both titles on the line. Buchanan left the ring as undisputed champion as he beat Navarro on points. Navarro had been a late replacement as the original opponent, Mando Ramos, had to pull out due to severe venereal disease… Buchanan’s list of physical difficulties were far less exotic as he cracked fillings in his teeth, leading to an enforced sparring break at the wrong time and a knee injury. The fight was a war, a very dirty affair which saw dirty tricks employed including stationing a Mexican under the ring at Buchanan’s corner to hear the instructions he was getting from his team, whilst there was also a strange woman offering to come up and see him sometime and then a tainted bottle of water on offer. It was no better in the ring but by the end Buchanan won a fairly wide points decision.

With the WBC belt around his waist, he was able to defend in the UK – surely. But it would not appear until boxing politics raised its ugly head and Buchanan was stripped of his WBC title as he did not defend against Pedro Carrasco. Now, only the WBA holder he returned to the United States and put that on the line in a rematch with Laguna in New York City. 13th September 1971: title defended successfully on points once more.

It was a fight that brought a legendary event into the realms of boxing history which was to make its way into boxing history and folklore. During the fight Buchanan suffered tissue damage around his eye that was so swollen that he could not see. His trainer, Eddie Thomas, sliced the swelling with a razor blade. Blood flowed, and Buchanan could see again. Much later it was Rocky v Creed in the original film that we saw the celluloid version.

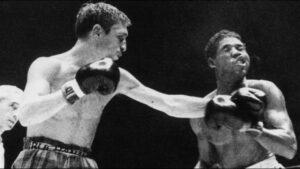

Madison Square Garden became a second home and Buchanan faced the first of two notable stern tests – one here and one at home. At Madison Square Garden, on the 26th of June 1972, Buchanan faced Panama’s undefeated Roberto Durán. Buchanan was to lose but in a fashion that has been much debated over the years. At the end of the 13th round, Durán was winning. When the bell sounded for the end of the 13th, both Durán and Buchanan traded blows, Buchanan with his fist, Duran with fist and knee. Buchanan hit the deck as Durán hit him low. Buchanan could not recover, and the referee gave the fight to Durán. The sense of grievance is still warm, as I type this. Ken Buchanan did not get stripped of his title, did not lose it on the scales and did not get legitimately stopped: Buchanan was robbed of it. Buchanan felt the effects of that blow for the rest of his life.

According to Christian Giudice’s Hands of Stone, The Life and Legend of Roberto Duran, Buchanan spoke of the fight as follows,” I was no longer world champion, and I was beginning to see how corrupt the sport was. It left a sour taste in my mouth.”

And whilst the United Kingdom appeared to be unable to honor Ken in the ring by getting a world title fight on for him in the UK, he was appointed an MBE by the Queen in 1972.

Buchanan bounced back from the defeat and took on a former three-time world champion in Carlos Ortiz, on the 20th of September 1972 back at Madison Square Garden. Buchanan was, however, expecting to go in and rematch Durán as the fight had been signed for the 10th of October that self-same year – 1972. No matter what the true record was of the first fight, surely it could be settled in a second. Instead Durán went on to fight in Panama rather than take the rematch and Buchanan was left with a dishonored contract deal.

Then came another contract which Durán duly signed for a fight in 1973. Surely now we could halt the debates and see who was the better of the two – Durán then refused to honor it, had his license from the New York Athletic Commission withdrawn and Buchanan was once again left, after a full two years of trying, of losing the chance to avenge the one defeat that rankled.

The second huge test came the following year – 1973 – when he faced Jim Watt back home in Scotland. Watt was a future world champion and star from the west of Scotland, whilst Buchanan came from the east. It was to be for the British lightweight title, and most believed that the young pup was about to school then old master. Oh, dearie me…

At the Albany Hotel in Glasgow, Buchanan outpointed Watt and regained his British title. Afterwards both became firm friends and when news of the loss of Buchanan was heard by Watt, who was out on a round of golf, he was reportedly devastated. Watt told Sky Sports, “I can hardly believe Kenny has gone. When I last saw him, he looked terrific, as if he could still do lightweight.”

Whilst the Watt fight was not a golden fight it showed that Ken Buchanan had plenty still to give – and that would include yet another world title fight. The road to which was not paved with gold but paved with more tough scraps.

The British Board, however, wanted a rematch and when a European title chance came up the prospect of a rematch was not something that Buchanan was going to entertain. And so, for a second time, the British belt was sent back to the Board by Buchanan.

He challenged again for that European title when he faced Antonio Puddu – beating him on the 1st of May 1964 in Cagliari with a 6th round stoppage. He then defended that successfully by beating old foe, Leonard Tavarez for the third time on the 16th of December in Paris – Tavarez’ corner threw in the towel – and then found himself fighting for the WBC belt once more – in Japan.

Up against Guts Ishimatsu, he lost on points on the 27th of February in Tokyo. Buchanan, having already suffered some dirty tricks when he had fought the first time for the WBC title found himself, once again, having to fend off some of the same types of nonsense. A sparring partner, apparently planted by the opposition stuck a thumb in his eye during sparring. He asked for a delay for the fight of a week as he recovered: it was denied. In front of 9,000 people on the night Buchanan was then hit on that eye at the end of the fifth and then could only see out of the other eye. From there he lost slimly with two cards and a Japanese judge gave it to Ishimatsu by nine rounds.

His European title was then defended against Giancarlo Usai with a 12th round stoppage in Cagliari on the 25th of July 1975 before he hung up the gloves in 1976.

Two years later he was back. From 1978 until 1982, his legacy was in danger as the toil of his lifestyle was beginning to make itself obvious on his battle-scarred body. Buchannan the fighter, who claimed to have started drinking at age 30 and kept going, was never shy from talking about his relationship with alcohol. It was a fight which was a consistent part of his life.

His final fight was on the 25th of January 1982, and this was a legend fighting for cash and not for belts. For around a year before the end, Buchanan was fighting for money and was desperate. His final fight, at the National Sporting Club in London’s Piccadilly, was where it ended, in a fight he took at three days’ notice. This was a legendary figure in hard times, doing the one thing he knew he was once good at, but this was also a legendary figure who was once good at it, no more.

The final few fights were against opponents who had no business being in the same ring as a man who had been a sparring partner of Barry McGuigan’s and who claimed had taught him so much. It was a tragic tale and hard to watch but Buchanan was that flaw in our genes. There had been none of the riches now available to him that are free flowing nowadays. To be fair had he made Millions, he would have spent Millions. Where some may have wasted it on alcohol and drugs, Buchanan would only have wasted his on alcohol.

There were relationship failures and business ventures that did not work out and he had to go back to being a carpenter to make ends meet. And it was whilst he was back on his tools that an undignified assault left its mark upon him.

It was tough, because those of us who grew up with his legendary status intact wanted only the best for him. It was clearly what he wanted for himself, and his final years dealing with dementia would have been as tough as the low blow he got once in MSG.

And it that legacy which endures as the most oft quoted tale is the one we remember most. Ina Madison Square Garde fight, where he was the headliner, a certain Muhammed Ali, along with his trainer asked if they could share dressing rooms as they had not had one allocated. Buchanan, with that twinkle in his eye, chalked a line down the middle of the room and told a man roughly twice his size what was what – that he needed to stay in his space or else there would be dire consequences.

Ali did not transgress and became yet another of Buchanan’s long-time friends.

But the fact remains that Ken Buchanan is the best boxer we have ever produced bar none, because he was one of us.

That others shall be measured against him is only right as this IBH of Famer deserves every accolade going, because he did scale the highest mountains despite being an ordinary guy, with a normal set of skills and the right belief system in place to show us who may face diversity how it can be done.

But let me finish with what Buchanan himself left us with in his final paragraph in his autobiography, the Tartan legend, apparently typed up as he was out sparring with Barry McGuigan. He wrote, “We’re all fighters, every single one of us., fighting is the first sport of every man and woman. From the minute we’re born, we’re fighting to breathe. Then we’re fighting to open our eyes. We’re fighting to walk and we’re fighting to talk. You can’t get rid of your desire to fight when that is the very first lesson in life. It’s just that some people hide it a lot better than others.”

And as I said, Ken Buchanan was the very best fighter we have ever produced, and hid nothing, though probably wished there were a couple of trinkets he could have done with hiding from a certain Mr. Duran….

Click Here to Order Boxing Interviews Of A Lifetime By “Bad” Brad Berkwitt