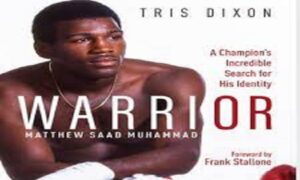

Ringside Report Book Review: Warrior By Tris Dixon

Book review by Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

2022; Pitch Publishing

“Mathew Saad Muhammad has accomplished boxing’s hat trick. He is the most mismanaged, mis promoted and now mis-trained championship fighter in America” Stan Hochman, Philadelphia News as quoted in Warrior by Tris Dixon, page 201.

They say that in everyone there is a novel waiting to be released. There is an accompanying cliche about boxers – they emerge from a tough life, over time are helped out their ghetto, make a load of money before those who were around d them rip them off and they die penniless.

Clichés are clichés for one reason – they are true.

In Warrior, the story of Matthew Saad Muhammad, Tris Dixon, formerly editor of Boxing News in the UK, tells this tale with authority. It is a story which should be easy to relate, however what raises it from a cliché into a compelling story is the way he tells it: it keeps the pages turning. The source material of a young boy at the age of 5, who was sent out with his brother, by his mother, to be left alone and abandoned is filed with tremendous detail but Dixon tells it with great understanding and sympathy – for all. It is easy to become outraged not just over the beginning but once Muhammad becomes Muhammad after having been Mathew Franklin, he gets financially abused. It was the time, of course, that boxing was bloated by advisors and people who did not have the sport in their hearts: Muhammad had more than the sport in his.

The tragedy is not just that he was let down, his faculties damaged by the wars he was in and the fact that as a child he was thrown out by the very people who should have protected him, but that he died before being able to see that story in print. Dixon had plans to include Muhammed in the production of the book, but by the end, Muhammad simply did not make it. His voice, however, is heard throughout thanks to Dixon having contacts beyond parallel, a relationship with Muhammad which included the fact Dixon was trained by him when he ended up in the USA as a young boxer. It also helps that his little black book of contacts brings voices of the time and those who survived them, offering a reflective point of view on the story that unfolded from Muhammad’s life.

It is a life that began with that event when he was left to fend for himself, followed by where his first known name came from – where he was found in Philadelphia – his first experience of bullies which led to his decision to make things change – “I wanted to protect myself,” he says. It was a decision which led to a pathway out of poverty but also away from a gang culture which drew so many young men into their ranks. Unfortunately, Muhammad it ended up in a juvenile facility as a young man whilst discovering he could take a heavy punch. By 1974, and upon release, he was to become the most active young fighter in the city.

Once we get to the fights that made his name – the title fights and the avenues of money rolling in – Dixon concentrates on the fights. Behind the scenes there are plenty of disturbingly normal stories and evidence of what we know is likely to happen in the long term – Muhammad never knowingly took a step back in a fight so was headily hit throughout his career. However, Dixon manages to mix both detail and fascinating insight. At times I found myself rereading elements of the chapters because they are filled with such panache. It includes some excellent material like how a champion became resented by some in Philly, how he struggled to initially get a title fight, how an inmate hovered around as a contender but that Muhammed would not end up facing him and how a future Hall of Fame reporter would report on one of his fights whilst still a cub starting out for Boxing Illustrated.

Of course, for us Brits, the two fights with Conteh stand out however Dixon’s sensitivity shines most when talking about Muhammad’s conversion to Islam and how his family – wife and kids – stayed with him despite his many battles. He also tells the story of how Muhammad decided he wanted to make contact with his birth family, which he did, after a national campaign. How it came about along with how it unfolded is fascinating. The humanity of a man who was abandoned by them shines throughout. His generosity matched his ferocity as he battled homelessness but also gave as much as he could to the homeless and was an advocate for better care for others.

Mathew Saad Muhammad was more than just the Warrior of the title but an example of humble humanity that may have sold the t shirt off his back to pay more of his way but probably would have given as much of that transaction to whoever he felt needed it more than he did. It is that level of detail that marks Dixon’s book out. By the end we have not just his passing but also the aftermath where people reflect upon his time.

It perhaps is where I felt we could have had more of this throughout the previous chapters however Dixon has made a case that the efforts of Muhammad are equal in so many ways to that of his idol, Muhammad Ali. One of the pieces of advice he got and ironically did not heed, came from Ali. Looking after his money was not his forte. Fighting was and this is a fantastic example of how to tell a difficult tale, with plenty to commend it. People who want to know more about a man who was not defined nor trapped by cliché but had the ability to straddle the world and teach us all about what is the most punishing sport in the world – inside and outside of the ring – makes this a Warrior worth heeding and reading all about him – he got his equal as a storyteller in Tris Dixon.

Purchase the book HERE.