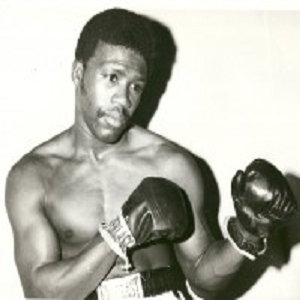

Ringside Report Looks Back at Boxer Samuel Goss

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

Mexico City 1968. The Olympics. One huge man in bantamweight shorts was Samuel Goss, 43-15-3, 19 KOs. The AAU flyweight champion in 65, he was now the AAU bantamweight champion and representing his country.

Born in Trenton, New Jersey, in the shadow of the end of the Second World War, he was part of that generation of sportsmen and women who were not alive for the battle against fascism but represented the fight for a new freedom. This was a new agenda, a new era and one in which they had the opportunity to lay out the pathway to what freedom meant and how it appeared to their generation and all the other ones which were about to follow. By the time Goss got to the Olympics, the sixties were swinging. Cuba was communist. JFK was gone, as was his brother, but the hope lingered that we were still looking forward to a new dawn, and a new era.

Goss came from a family steeped in boxing as his father and brothers boxed. By the age of 15, the bug had bitten him. Looking up at his brother, Barry, who was a boxing star in the amateur code, Sam had not very far to look for inspiration. And so, he asked his dad if he could box too. His father told him to read books… but also sent him to Trenton P.A.L to learn.

And what a learner. Prior to the Olympics, Goss became 5 times a Golden Gloves state champion, 5 times an AAU state champion, was runner up at the National Golden Gloves and then won the Olympic trial.

Goss’s Olympics, however, was as short as the miniskirts as he went in against Romanian Nicolae Giju and returned chastened by a whitewashed 5-0 points defeat. He was competing in a category won by the Soviet Union’s Valery Sokolov who went on to become the Soviet Union’s national boxing coach – communism to the left of us, and to the right…

Way back in 1983, in the New York Times, Goss was reflecting on his experiences in the amateurs and talked of the long ride by bus he took in the sixties to compete at his first Golden Gloves. ”… during that ride I was thinking and thinking. The fight was my first one (I was a flyweight, the lightest class) and all the people out in the seats were screaming. My feet were frozen, and I got popped. ‘I was scared. Yup, scared, but I remember thinking, ‘That’s the last fight I’ll ever lose. And the last time I’ll be scared.’

Of course, it was not the last fight he lost but it was a chastening experience and one that began a glittering career.

Once back from the Games, Goss quickly turned over and made his professional debut on the 20th of February 1969 in Portland against Henry Wickham and won by first round knockout. Having won his favours by a philosophy from father of 10 children, Jessie, Sammy was now going to find out if that philosophy – of work hard, play hard and be honest would bring him some riches.

Goss fought for a long time and had quite a distinguished career in the professionals. Though he never boxed for a major title, he did have 61 professional contests. He lasted from that debut in 1969 all the way to 1981. Along that road he did get close to fighting for a world title – in 1973, when he was the number one contender for the world title but the opportunities, he needed never led to a title fight.

Along the way he did pick up some belts and on the 10th of August 1971. In Philly he stopped Lloyd Marshall in the 7th round to pick up the NABF super featherweight title. On the 9th of March 1973, in Madison Square Gardens, New York, he kept it against Walter Seeley with a points win.

Of all the fights his 1973 dust up with Jose Fernandez for the US super featherweight title was the pinnacle as he won the title. No wonder by the end of the year he was climbing those rankings and being seen as the number one contender.

But 1974 was tough. As in really tough – 5 fights, 1 win. In April he was knocked out in the 2nd round of a fight with Tyrone Everett. He was no longer the US champion. In 1975, in San Carlos, Ray Lunny III also stopped him in the 8th round for the NABF super featherweight title.

Title fights eluded him as he tried to build back up again. He was losing far more often than winning but in 1979 a 10-round fight, against Augie Pantellas brought him, according to his feature in the New York Times, a significant paycheque – $25,000. He lost and made sure he spent it – “I bought a new car and a new house, and I was the king of the world for a long time. The wife’s got the house now. I don’t go in it. But I don’t know anyone who lived it up like I did, who had what I had.”

His final fight came on the 14th of December 1981 in Durban against Brian Baronet. Stopped in the 7th round, Goss never went back in the ring to fight again. He was 34 years of age. In his interview it was a time he recalled with few regrets but perhaps only one, ”maybe I fought a few too many fights and should have quit when I turned 30, but leaving behind your profession is tough for anyone, especially an athlete.”

It is rumored that it took Boxing Commissioner and former world heavyweight champion, Jersey Joe Walcott, to tell him that, “he would be more effective helping young boxers outside the ring.”

Having retired, Sammy and his brother Barry were still very active and, as Goss and Goss, were often to be found in the corners for amateur fights locally in Trenton. It is an area blighted by poverty, but it is where the Goss brothers call home. But both managed to escape the perils of the slums by being actively involved in the sport and have been giving back to their community by offering others the same hope from which they benefitted. It’s a dedication he reminds us is a vocation in his intervei9w way back in the 80’s as he said, “’I see all sizes of kids come and go at the gym. ‘I don’t try to discourage them. I don’t tell them that only a few can make a dollar by fighting. I teach them that they must have dedication. ‘Most of them show up at the gym once a week, hit the heavy bag for five minutes and skip a little rope.

Then they go into the ring to spar, take a shot in the belly and go down. ‘The kid who is here every day to work out for two hours may not become a good fighter, but he’ll be successful. I know ’cause I see it every day.’

Click Here to Order Boxing Interviews Of A Lifetime By “Bad” Brad Berkwitt