Ringside Report Looks Back at Harold Volbrecht

[AdSense-A]

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

By Donald “Braveheart” Stewart

The 1970’s and 1980’s caused a lot of concern for anyone in politics in the United Kingdom when it came to South Africa. Whilst other nations had wars to rally against and conflicts on foreign fields we were dealing with a growing threat of terrorism from within and our legacy as left in colonies and formerly UK ruled countries that were now causing international concern.

One of those was South Africa. As Rhodesia imploded into Zimbabwe and the apologists for colonial rule were forced to concede that our influence in Africa was not a “wholly” positive one, South Africa clung on to the idea of racial superiority like a long past his sell by date and battered boxer after the third round, hoping to hear the final bell.

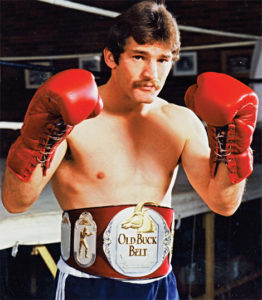

There were many within South Africa who held no or radical political opinions but were caught up in boycotts, the international shame of Apartheid and the lack of opportunity that afforded to develop from a prospect into a champion. From 1975 until 1989, one such fighter was Harold Volbrecht, 47-5-2, 14 KO’s.

The lack of opportunity for him was such that Volbrecht only fought outside of his native South Africa on 4 occasions and 1 of those was in nearby Rhodesia.

His travels were never fruitful though he fought not once, but twice for a world title. Such experience may actually have held him in good stead as it is his record as a trainer that is more noticeable than as a pugilist that makes the mark with true boxing fans today.

It is, however, also a story that touches on a thankfully, long experienced past in a country of great beauty who are still trying to reach the pinnacle of being the heir to Nelson Mandela’s legacy.

Volbrecht made his professional debut in 1975 and it was a very impressive one, with a first round knockout. His first three fights ended in the same way – by him knocking someone out. His first defeat was in 1976 when he was knocked out himself and before long the lack of decent fights and fighters became obvious as he fought Gert Creamer three times – one draw and two wins, one of which was for the South African (White) welterweight title; in Apartheid times such disgraceful titles were all that were available for fighters to scrap over. Of course, we should not crow in the UK, we had the British Empire belts to compete for.

By 1978 it was now the South African welterweight title and he fought and won it twice before being catapulted into world title contention; his other fight in foreign fields in 1978 was in Harare, Rhodesia and he lost.

Five years into that professional career and he was fighting for a world title for the first time, in Houston and in against Pipino Cuevas – in a hard fought and tight contest he lasted until the 5th round where he was knocked out by Cuevas – one judge had him ahead, the other two behind by one point; so close but yet so far.

The recovery took 20 fights, 18 wins, 1 loss and 1 draw; 11 of them for the South African welterweight title. It also took 7 years to get back in a world title fight though 1985 was lost to Volbrecht due to a car accident and his title pretensions were helped by beating contenders for the title put in front of him.

All of these 20 fights happened in South Africa so they would have been away from the international cameras but were clearly in the conscience of one governing body – the WBA. In 1987 he was back in the ring for that WBA title, in the Trump Plaza in Atlantic City, however politics was very much at the heart of the fight; given the venue, how ironic.

Volbrecht in the run up to the contest was sure he could win, saying of his opponent, “I think he’s a little overrated. He jumped from No. 10 to No. 2. I can’t see him jumping over fighters like Johnny Bumphus or Marlon Starling. I don’t think he’s fought anybody in my class yet.”

Breland was the harder puncher of the two though the political punches were the most significant of the fight. This had originally been a unification bout as Lloyd Honeyghan was to be next. Honeyghan held the WBC and IBF titles and rather than fight Volbrecht, relinquished the WBA belt. Honeyghan put it in the bin, didn’t tell his manager, Mickey Duff he was doing it and looked like he was taking a principled stance against apartheid. According to British boxing commentator, that is a view that “is too simple an explanation.” It was a view that bought Honeyghan a lot of fans.

Volbrecht though was a guy who had taken a stance against Apartheid, fought int the minority townships and had won the “Supreme” title – all colors – South African belt a few time sand would go on to defend and win it a few times more. It gave Honeyghan a few more fans and some more of a spotlight onto the issue of Apartheid. For c=boxing though, it did very little.

Volbrecht was unhappy that this was an issue that had come to dominate his preparation and he spoke out, “I don’t want any politics to worry about when I train.” His manager, Carlos Jacomo, went further, “We would really like to leave politics out of this. I sent a telegram to (promoter) Dan Duva opposing apartheid, I don’t know what else I could do. You would not bring this up to a fighter from any other country.”

In the end Volbrecht only lasted to the 7th round of 15 as Mark Breland stopped him; he was ahead on the scorecards at the time but the historical part of it was that Breland was the first 1984 US Olympic Gold Medalist to win a world title.

It was a fortunate end for Breland as he admitted afterwards, “”During the fight, I felt a shock going all the way up the shoulder when I threw the jab. Even when I missed, I felt the shock. I had to clench my fist real tight.” It was a broken hand he felt, and it was not the first time this had happened, he first broke the hand months before while training for a bout against Reggie Miller. ”I broke my hand but didn’t know it; I thought it was just a nerve problem.”

Unlike many pros, Volbrecht’s career ended with wins rather than defeats – 8 in a row from May 1987 to the final fight in Sun City on the 25th February 1989. Three of them had been for the South African welterweight title, now completely devoid of its racist overtones and his transfer from being a fighter to a trainer was on its way; mirroring the transformation of his country from international pariah to a state of virtue under Mandela.

Post fight, he remained loyal and true to his country and stayed to train fighters where he was to be involved with many prospects in the country.

Volbrecht opened a new gym in 2014 and the future appeared not to be wholly bright but likely to give him a new lease of life and the South African arm of the sweet science some genuine hope about which to cheer. But whilst Volbrecht faced the troubles of being from a country nobody talked to, there is one fighter he trained that he knew had the world at his feet but did not step up to the plate and make a difference to his life and those around him in a more positive fashion.

By this time Volbrecht had got Corrie Sanders to the WBO belt and had established his reputation, not just as a former Apartheid era boxer but as a trainer of some standing; he was developing a stable of prospects.

This was Tommy Oosthuizen. Oosthuizen’s time with Volbrecht was far from straight forward and by 2016, Volbrecht had run out of patience with his fighter. He even went on to describe his time with the fighter as “a nightmare”.

Oosthuizen had been an IBO super middleweight champion by this time and a few were murmuring that Volbrecht was not controlling him enough but Volbrecht was happy by this time to hit back describing things thus, “I pull him out of bars, I bail him out of police stations, I get him out of street fights. My wife Michelle and I feel betrayed. We’ve tried for so long to keep him on the right road. As soon as he comes right, he veers off again. We’ve looked after him daily, doing the things his parents should be doing. He could have become one of the greatest in South African boxing, but he’s wasted everything. We’ll always wonder what might have been. He drops appointments, he lets people down. He just doesn’t understand. It’s all about him. If Tommy had a day job, clocking in and clocking out, he would lose his job. I’ve tried and tried. I can’t do this anymore.”

What made it even more difficult to stomach was that Tommy Oosthuizen was the son of former two-division South African champion Charles Oosthuizen.

Oosthuizen is still active, now a cruiserweight and fighting for titles. Volbrecht is still training and with a legacy that will live longer than many. Perhaps not the South African fighter most think about when thinking down the south of that great continent but we need shoulders upon which others may stand to be the champs who face the champs; Volbrecht’s shoulders appear very worthy for those who want to achieve greatness.

[si-contact-form form=’2′]